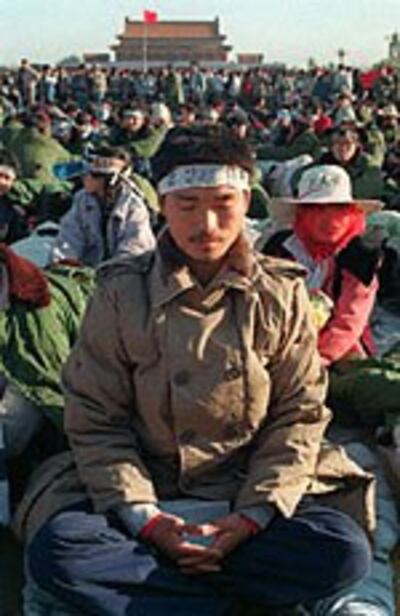

Jill Ku: Listeners, welcome to “Different Voices.” I am Jill Ku...Today, Mr. Yang, a PLA soldier who carried out secret arrests in Tiananmen in 1989, will take you back again in front of the tanks and machine guns in Tiananmen Square. Back then, how did the PLA detain people, how did they kill people? How did the soldiers feel as they cracked down on the students? After the slaughter at Tiananmen, Soldier Yang never dared to discuss his experience with anybody. Today we will uncover the secrets he has kept hidden in his heart for all these years:

Yang: On June 4th, I was there myself and took part in the incident. It wasn't our People's Liberation Army soldiers who did wrong. It was the leadership of the PLA that made mistakes. We had absolutely no choice. At that time, we carried out special operations. We didn't directly participate in the crackdown on the students. We were in Tiananmen.

Ku: OK, could you describe a little bit about the situation then? Just now you said that it wasn't the PLA soldiers' fault; it was the fault of the PLA leadership.

Yang: At the time, we saw the students sitting quietly. They were showing their strength through a hunger strike. We asked the leaders to look at this and said, “Look at their ability to resist. What can they do? They're just sitting there. What do we need to come here for?” You know what the leaders said? They said, “It does not matter whether it is necessary or not. Do whatever I tell you to do.” At the time, many people said in that case we really feel sorry for those students. We are all Chinese. The leadership just didn't care about these things. They just use military discipline to force you to act: "You are a soldier. Carrying out orders is a soldier's fate. And you have to do it." So, from 1989 to today—I've already been retired many years—every time I think back on this, I don't feel at peace psychologically.

Ku: At the time, under orders from your superiors, what kinds of activities did you carry out that made you feel so uneasy?

Yang: Mostly we were—we weren't doing a large-scale crackdown, that kind of thing—mostly we were, after the leaders determined the goal, we were secretly arresting people ...

Ku: Secretly detaining what kind ...

Yang: ... and sending them to Black River Farm [a prison camp in Helongjiang Province].

Ku: Black River Farm. How many people did you secretly arrest?

Yang: In all, our special sub-unit secretly detained 22 people...At the time, we were in plain clothes and we did the job from a car. The leaders used walkie-talkies to tell us: “Get out of the car now. Walk east, walk west, so many meters, there is a person wearing such-and-such clothes.” That was the way it was done. Our job was to get them and arrest them, and then turn them over to another department to handle. Later, I heard all of them were sent to Black River.

Shooting by special unit

Ku: What kind of treatment did they receive, do you know?

Yang: Their treatment definitely wasn't so great...We didn't have any idea what kind of role they played. We had no way of knowing. We weren't allowed to open the curtains on the windows. We all just sat in the car listening to the orders on the walkie-talkie, and after receiving orders, we got out of the car. And we went in the direction we were told and when we got there and saw that the clothes on those people matched the descriptions given to us based on our superiors' intelligence, we just grabbed them.

Ku: Do you know, of the people who were carrying out this job with you, were there any people who...killed people?

Yang: It seems that there were, in the Fourth Central Special Unit. I heard that Fourth Central Special Unit carried out a beautiful job that day. They shot a target at a distance of more than 150 meters.

Ku: They shot the person down with only one bullet.

Yang: Right.

Ku: In their eyes, this was a very beautiful job?

Files rewritten to conceal crackdown

Yang: I don't understand why they felt that way. Anyway, after I heard, I felt very uncomfortable.

Ku: If you had to do that job, how would you feel?

Yang: My feelings? From an emotional perspective, as a human being, that kind of job is impossible. But from the perspective of a soldier's duty, I would have to do it. I couldn’t have even the slightest hesitation. I saw those female students, they really were just skin and bones from hunger. When I pulled them into the car, even then they couldn't walk because they were weak from hunger. When they got in the car, one of them said to us: “Right now you don't know what we're doing this for. You'll certainly understand later.”

Ku: What did you think at the time?

Yang: I didn’t feel very comfortable, but no one would dare to release her...

...I wouldn’t tell anybody that I was at Tiananmen around June 4th, doing those things. I certainly wouldn’t dare to talk about it. The files of the four special units assigned to the mission were all rewritten.

Ku: What do you mean “rewritten?”

Yang: Our special unit number, our duties, were all changed in the records, so that we couldn’t be connected to the incident.

Ku: So in your file there is no record whatsoever of that work.

Yang: None at all! The notation in the file states that on June 4th I was doing training in Qinghai province...

Ku: How many People’s Liberation Army soldiers would you estimate were on Tiananmen Square that night?

The notation in the file states that on June 4th I was doing training in Qinghai province...

Yang: You mean when the military force was at its greatest?

Ku: Yes.

Yang: I would estimate there must have been about two fully equipped regiments.

Ku: These were all armed, carrying machine guns, driving tanks onto the Square.

Yang: I think so. From my vantage point, I’d say there were about that many people.

Ku: Often, over the years, we’ve heard the opinions of many in China—especially the younger generation—who just don’t believe that people died on June 4th. They don’t believe there was suppression. So as someone who was assigned to the mission there, could you tell me how many students might have been killed?

Yang: I can't make a concrete estimate, but what I myself saw was not less than 20 or 30 people...

Ku: In the eight years of your military life, you were assigned to be part of the Tiananmen suppression in 1989. Can you please describe how you feel about participating in such a mission in the context of your eight years of military life?

Yang: I regret it very much. I can only say I regret it. I can look inside myself and say that, although I was there to carry out my assignment, to arrest people, I never had any innocent blood on my hands. At least that is something I don’t feel guilty about. But I am very sorry that I had that kind of assignment. I never thought the government would do things that way. Tanks, earthmovers, and flame throwers were all used there.

Tiananmen veterans under supervision

Ku: You wouldn’t dare to tell people that you were at Tiananmen Square.

Yang: I wouldn’t even dare to tell my wife...Before we got transferred, the officers of each special unit ordered us never to tell anyone we were on Tiananmen Square. They said we should let it rot in our minds and take it to the grave. We were not even allowed to tell our parents, children and wives. If your wife asked you what you were doing during the 1989 movement, you would tell that you were doing special training in Qinghai...We have regular meetings talking about what we have been thinking, what we have been doing, and whether the old soldiers have made any mistakes. We have to report everything.

Ku: Oh, is that so? How often to you go to these meetings?

Yang: Usually it’s every three months.

Ku: You have to report to them every three months?

Yang: After three months, the local military supplies department notified you to go. I went and we had a tea and discussion meeting. It was called a tea and discussion meeting, but actually they called us there to give us a warning...Then, we generally all were promoted two steps. The worst were promoted one step.

Ku: You were promoted too?

Yang: I was promoted two steps. They broke a rule and promoted me. At the time, I was a soldier. After it was over, I was promoted directly to company commander.

Ku: In other words, you benefited and were promoted two steps for this job. But that gives you conflicted feelings.

Yang: You couldn't say, "I don’t want to be promoted." Even if you beat me, I wouldn't dare to say that. The Center decided on it; it had the special approval of the Central Military Committee. They give you the opportunity to be promoted by doing something wrong and promote you two steps. All you and say then is “thank you” to the Central Party, “thank you” to the Central Military Committee. What else can you say? You can't say, “I don’t want to be promoted.”

I wouldn’t even dare to tell my wife...Before we got transferred, the officers of each special unit ordered us never to tell anyone we were on Tiananmen Square. They said we should let it rot in our minds and take it to the grave.

Ku: But how did you feel inside? Were you happy?

Yang: I'd rather they let me drop out of the army and leave it at that. I was afraid. People have a saying about major incidents in China occurring every 10 years. So, that's 1989 to today, 1999.

Ku: You just said you were afraid. What are you afraid of?

Yang: ...China is at a point where it can't go through this turmoil again. To go through this kind of turmoil once is as much as we can take. If it happened again, we'd be simply hopeless.

Ku: So you've decided that 10 years ago this movement brought turmoil to the nation. Wasn't there anything good that came out of it?

Fears for further turmoil

Yang: At the time things were stirred up, so people were alarmed and anxious. People from perhaps every walk of life were affected. My feeling is that, except in Beijing, more than 10 years after the movement many people from other places have already forgotten. When it occasionally comes up, it's still like a frightening secret—hide in the house and shut the doors and windows tightly and talk a little. It's just a topic to discuss after dinner or tea. Cruel realities such as stiff competition, layoffs—those kind of things—have made people unable to think about these kinds of things...

Ku: Would you like to reveal what kind of job you're doing now?

Yang: Now, I—to use your American language, I'm a businessman. I sold so many years of my life to the Communist Party and, after all that, if I catch cold, I have to ask the doctor to use the cheaper injections. So, I've figured it out and I decided to make a little money. That's the right thing to do. My goal is very simple: Make enough money to take my wife and son to Hawaii and sit in the sun. That's my goal.

Ku: Are you trying to get away from the psychological burden?

Yang: We just want to be human beings for a few days. While you can still chew things. You don't want to wait you've lost all your teeth and still have not lived even a few days as a decent human being. I want to understand what it means to be a human being...

...I won't talk big and list things that I can't do—things about making contributions to the country, struggling for democracy, struggling for anything...I've already been ground down to the point where I simply have no sharp edges! All I can say is, if I had a list of the parents of those students, I would certainly help them out economically. I would do as much as I could.

Ku: Do you feel that you wronged these people?

Yang: I obviously participated and I bear some of the blame. It was the government who wronged them most, but the government won't provide any compensation, so the people who participated will have to compensate them. Regardless of the cause or the circumstances. After all, I participated.

Interview broadcast June 5, 1999. RFA Mandarin service director: Jennifer Chou. Produced for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie and edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.