In Tokyo, I got a taste of what it’s like to break a big story.

I was 27 years old, working on my first job on the overnight desk at the Asia headquarters of United Press International.

At around midnight on Oct. 16, 1964, Xinhua, China’s official news agency, reported that it would soon have an important announcement.

UPI couldn’t get into China in those days, so we carefully monitored Xinhua.

I got overnight editor Art Sakai ready, and I stayed glued to the Xinhua machine.

We were high above the Tokyo streets in the Mainichi Shimbun building.

I saw the first report on the A-Bomb on the Xinhua wire at around 1:00 a.m. and started filing a story in one–paragraph bursts to New York.

Hero for a day

Joe Morgan, the foreign news editor in New York, shot back with a message saying that I was more than five minutes ahead of the Associated Press, our chief competitor.

In the wire service business, that gave UPI a huge lead. We broke the story just as afternoon newspapers on the East Coast were going to bed.

“Spike the ocha all around!” messaged Morgan, meaning roughly, “Put some booze in the Japanese tea!”

The New York World-Telegram, a leading afternoon paper at the time, bannered the story on its front page in language typical of the time: "Red Chinese Fire A-Bomb."

I’m guessing it was sheer luck that I was ahead on the story. How could the AP fail to move as fast as I had? Someone on duty in the AP office must have been distracted at the same time that I was pounding the typewriter.

I quickly learned that beating the AP was the name of the game at UPI. A few minutes’ break on a story at a critical time of day could make all the difference.

But I also learned that in the wire service business, you can be a hero one day and forgotten the next. I heard more than once, “You’re only as good as your last story.”

The Lin Biao fiasco

At one point in 1964, I found myself on the night desk reading a Xinhua report on a speech by Lin Biao, the Chinese defense minister, who would soon emerge as a short-lived successor to Mao Zedong.

The speech was a diatribe against the United States—essentially a propaganda statement. But it sounded more like a declaration of war.

I wrote it up without providing any analysis or context, but we got big play with the story back in the U.S., where many readers were ready to expect the worst from an aggressive China.

I should have provided more context.

The story triggered a debate among UPI managers and editors both in Tokyo and at our New York headquarters.

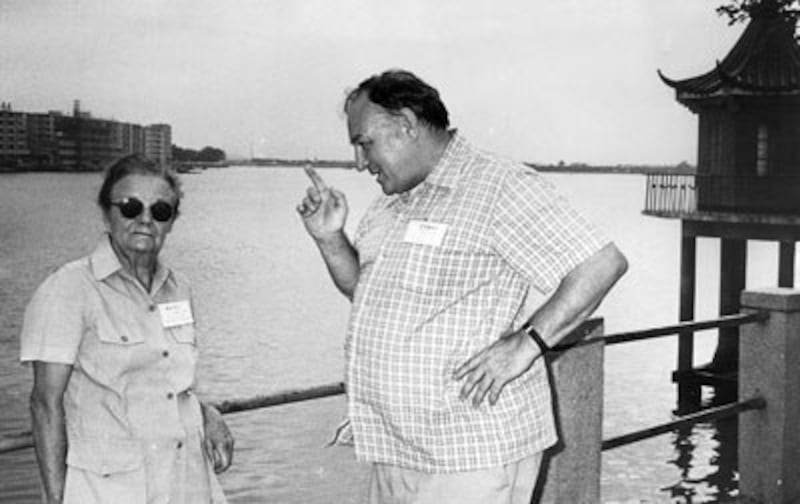

Ernie Hoberecht (pronounced Ho-bright), UPI’s Tokyo-based manager for Asia, defended the story, arguing that I had correctly quoted Lin Biao. Others thought that I should have played down Lin’s histrionics. Clearly, they were right.

Cold War China watching

I had studied the Chinese language and Chinese history, so in theory I qualified as a China watcher. But UPI’s ace China watcher was Charles R. Smith, the agency’s first chief correspondent for China. He worked mostly out of Hong Kong, where he kept in touch with professional China analysts.

As Bill Wright, a veteran UPI newsman, described him to me, “Charlie was a fierce competitor with the AP—and his own colleagues—and often won against the AP.”

“In those days we depended mostly on official China news media to report on the country,” said Bill. “Charlie could take those reports, analyze them, and come up with an incisive story lickety-split.”

Charlie happened to be in Tokyo when we broke the A-bomb story, so I called him at his hotel the moment we got the first bulletin out. He came in and banged out one of his famous analysis pieces.

Charlie was one of those wire service correspondents who could write about anything. He ended his career as a writer and owner of The Asia Letter publications, and died of a heart attack at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Hong Kong in 1996 at the age of 66.

Making predictions about China for radio

In addition to my editing and reporting from Japan, I did radio reporting for UPI and in one or two cases made year-end predictions about China. I began to learn that making predictions about a closed-off country like China was risky business.

Tom Foty of CBS Radio News, a former UPI Radio manager, recently passed on to me an audio clip that he’d saved in which I expound with great authority from Tokyo on China’s activities in Asia in 1965 and what might be likely to happen in the following year.

I accurately summed up China’s setbacks in Indonesia in 1965. I also said that China would probably avoid direct military intervention against the United States in the Vietnam War, which also turned out to be correct.

But I had no clue that Mao was about to unleash China’s destructive Cultural Revolution, and I predicted wrongly that the Chinese economy was likely to continue to grow.

I was also wrong in suggesting the possibility of another major Chinese attack against India.

In the end, I realized that I was never going to be another Charlie Smith.

Later, after the American military began a massive build-up in Vietnam, I volunteered to end my career in Tokyo and engage in new battles against the Associated Press in Saigon.

In early 1966, I asked UPI to send me there.

I returned to China watching, this time not from Tokyo but from Hong Kong, after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975.

Dan Southerland is RFA's Executive Editor.