For the people in the tiny Lao villages that dot the mountains in the land-locked country’s northwestern border, the banana looked like a savior.

Demand for bananas in neighboring China was skyrocketing, and Chinese investors rushed to build banana plantations in Laos’ impoverished northern provinces.

The plantations helped satisfy the demand for bananas in China, and even though the pay was low, it was better than no pay at all, so villagers flocked to the plantations looking for work.

For a time, everything appeared to work the way it should: Lao laborers had work and the Chinese gained a new source for bananas and the profits they brought.

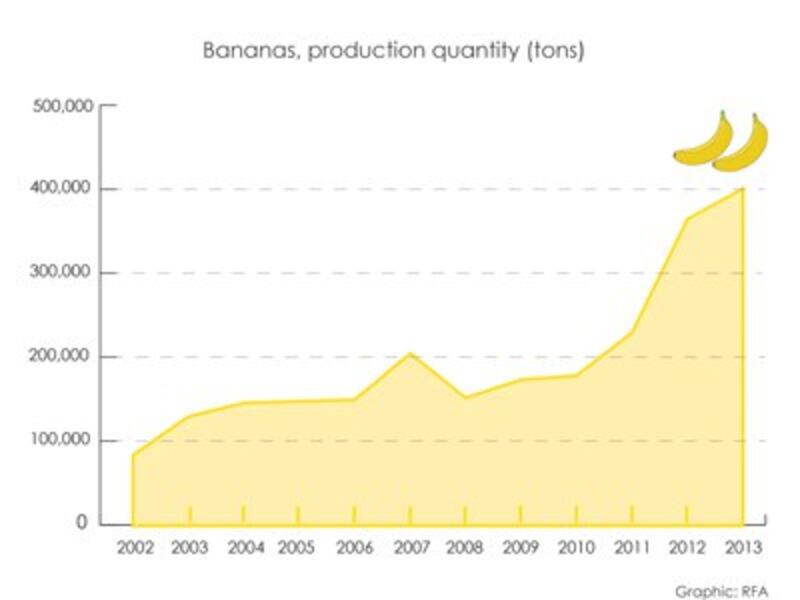

While Laos isn’t among the world’s top banana producers, banana production there has exploded. In 2002, Laos produced less than 90,000 tons of bananas, but by 2013 it was producing more than 400,000.

Eventually, however, things began to go sour, and the Lao people began to wonder if the banana deal they made with their neighbors was a good one.

Unlike in South and Central Laos where the bananas are easy to grow, Mother Nature needs help in the provinces of Bokeo, Luang Namtha, Phongsaly, and Sayaboury.

The Kuay Nam vs. the Cavendish

Instead of the native “kuay nam,” the Chinese plantations generally grow the world's top banana the Cavendish.

“The difference is that in the north, the Chinese invest in banana plantations with commercial types of bananas from foreign countries, and they require fertilizers and chemical substances due to the many diseases and pests,” explained Vongpaphan Manivong, a researcher with the Lao National Agriculture and Forestry Research Institute.

“In central and southern Laos there are native banana plantations that use almost no fertilizers and chemical substances,” he added.

To ward off the 28 diseases and 19 insects that attack banana plants in the north, plantation owners turned to a cornucopia of pesticides, herbicides, rodenticides and fertilizers to boost production.

While the chemicals helped the banana plantations thrive, they didn’t help the banana workers or the plantations' neighbors.

The chemicals leached into the ground water and the thousands of plastic packages that the chemicals were packed in were strewn across the countryside, causing worry about contamination and, in one case, the pollution was blamed for a death.

“Chinese plantation owners throw the waste, including fertilizer and plastic bags, plastic bottles of pesticides and insecticides into the stream the villagers use for their livelihood,” a resident of That and Phokham villages in Luang Namthan province told RFA.

“The plantation owners do not manage the waste, and villagers are not happy with it because during the rainy season the chemical substances will be swept into the stream so no one dares to take a bath in there,” he said.

In Simeuang-ngam village the runoff from a banana plantation was blamed for killing 900 kg of fish, and the Chinese investors backing the plantation found it cheaper to pay compensation than to prevent the contamination, according to local sources.

“The fish in the pond died, and the Chinese plantation owner paid the fish pond owner for compensation,” a villager told RFA. “Chinese investors in the banana plantations do not pay attention to preventing the environmental impact.”

U.S. $62.50 for a dead man

Banana plantation workers who got the most exposure to the chemicals began to get sick, villagers told RFA. Open sores formed on their arms and they began to get headaches and dizzy spells.

A government official in the Pha Oudom district, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told RFA that one worker died from exposure to the chemicals.

The official told RFA that the banana plantation owner gave the victim 500,000 kip (U.S. $62.50) when he was treated in the hospital, but when he died his family wasn’t paid.

Conditions for banana workers are so bad that plantation owners only allow them to work on a plantation for three years because they fear they will die there, sources tell RFA.

In February armed Chinese guards forced Lao workers in the country’s Oudomxay province to labor in banana plantations, a local village chief told RFA.

A chief of the Nongbouadeang village in the province’s Houn district told RFA that 50 Lao workers in a Chinese-owned banana plantation in the neighboring village of Nammieng were working under Chinese overseers armed with automatic rifles.

“The plantation owner uses the weapons because he is scared that Lao workers will resist his orders, but he does not have permission to have firearms," said the chief. In Laos the ownership of firearms is tightly regulated.

While China and Laos have had an off-again, on-again relationship, Beijing has been pushing for closer ties. China has vied aggressively for influence in Laos through aid, loans, and infrastructure investment.

China is now the biggest foreign investor in Laos, with Beijing claiming to have pumped nearly $6 billion into the country in 2015. China is also bankrolling a $7.2 billion high-speed railway project.

While deepening ties included the banana plantations, the cavalier attitude about pollution has also deepened Lao concerns, at least locally.

Concessions suspended

In Bokeo province, Governor Khamphanh Pheuyavong suspended new land concessions for bananas, citing the pollution of the water supply and the health concerns of the workers, including the laborer who died. Khamphanh Pheuyavong’s decision came after a government report found that the minuses of the banana industry in northern Laos might outweigh the pluses.

Vongpaphan Manivong told RFA the problem doesn’t lie so much with the chemicals used, but with the way they are regulated.

“I do not mean the banana plantations are not good, but provincial agriculture sectors cannot manage the waste, chemical substances and fertilizers,” Vongpaphan Manivong. “The provincial agriculture departments do not have any records of fertilizers and chemical substances that the plantation uses.”

In his research, Vongpaphan Manivong found that chemical counterfeiting was rampant as banned chemicals are imported with new labels slapped on them to fool Lao customs officers. Researchers found nearly 50 different chemicals bound for the plantations that were either banned or faked to look like they were approved.

Vongpaphan Manivong told RFA the dearth of enforcement allows unscrupulous plantation owners to use banned chemicals.

“Some fertilizers and chemical substances that are banned from use in Laos as well as China, are still somehow imported,” he said. “The border checkpoints in the north cannot control the dangerous imports.”

Reported and translated by Ounkeo Souksavanh for RFA's Lao Service. Additional reporting by Brooks Boliek. Written in English by Brooks Boliek.