Laos said it will begin formal construction on the controversial Don Sahong dam on the Mekong River in December, vowing to proceed with the project transparently to assuage fears over its potential environmental impact.

Preparatory work on the 260-megawatt dam began in July last year, but full-scale construction will proceed “in the beginning of December,” Deputy Minister of Energy and Mines Viraponh Viravong told the media during a tour of the project site.

“Work on a bridge and access roads are already under way,” Viraponh said.

“By the end of the year we will close the cofferdam [which allows water to be pumped out of the site] and will begin work on the Hou Sahong [channel],” he said.

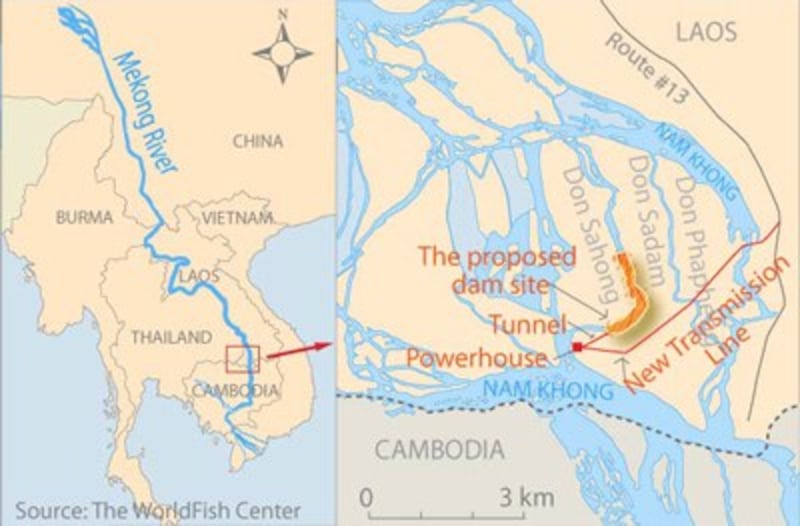

The Don Sahong dam is to be located slightly more than 1 kilometer (0.75 mile) from the Lao-Cambodia border, will block the Hou Sahong channel—which environmental groups say is the only year-round channel for transboundary fish migration on the Mekong.

Viraponh said that contracts to purchase the electricity produced by the dam had already been signed, with the concession to Malaysian dam developer Mega First Berhad mapped out and sent to lawmakers for approval, and that a loan agreement would be completed by May.

The electricity generated by the project will be fully sold to the national power utility Electricite du Laos (EDL) to meet increased demand for domestic power, state media reported.

He expressed confidence that the project “will bring development to the local area,” claiming it would have little impact on the region because it is a spillover dam that does not require flooding for a large reservoir.

“The people of the area will have a new way of living,” he said.

Viraponh spoke during the second day of a tour of the site for more than 100 representatives of member countries of the Mekong River Commission (MRC)—an intergovernmental body which oversees development on the waterway—development partners, international nongovernmental organizations, and Lao and foreign media.

The two-day visit was organized by the Lao government and Mega First as part of a bid to demonstrate transparency for the project and to address concerns over its impact on the environment and on riparian communities who rely on the Mekong for their livelihood.

Environment groups, including International Rivers, had warned that the project—part of Laos’s plans to become the “battery” of Southeast Asia by selling electricity to its neighbors—“spells disaster” for fish migration on the Mekong and threatens regional food security.

Villagers’ concerns

On Wednesday, villagers who will be relocated to make way for the dam told members of the media that they do not oppose the project, but want Mega First to provide them with an alternative to fishing, which they currently rely on as a source of food and income.

“If there is no alternative livelihood for us, we villagers are likely to stand against the project,” one resident said on condition of anonymity.

He said that the developer should provide assistance and jobs that would allow them to draw an income comparable to what they earn from their traditional work catching fish.

Another villager said that officials previously visiting the area had explained to residents that the project would introduce new jobs, though it had been more than a month since they had heard any more information.

“On Jan. 27, they came to meet the villagers asking about our needs,” he said.

“They said that they would provide some sort of funding as assistance for us and that we would be able to pursue work in fields like animal husbandry, fish breeding, growing vegetables, or whatever we like.”

He said that he hoped the project developer would support them according to what they had been told during the January meeting, but expressed concern because there had been no follow-up discussions.

On Wednesday in Champassak province, ahead of the visit to the dam site, Viraphonh told the delegation that the government has demanded that developers conduct extensive research on all potential environmental and social impacts of proposed hydropower projects, according to a report by the state-run Vientiane Times.

“We insist that studies be done professionally and thoroughly by recognized international experts and that the resulting analysis and technical data be disseminated wholly and honestly with other qualified experts for discussion,” he said.

Viraponh said that the government would continue to welcome comments from MRC member countries, development partners and environmentalists so it can improve the project's final design and ensure its sustainability, according to the report.

Potential impacts

The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) said recently that blocking the Hou Sahong channel would cause “permanent damage” to the Mekong basin’s fishery resources, which it valued at between U.S. $1.4 billion and $3.9 billion per year.

The group contends that water quality, sediment flow, habitat degradation, and increased boat traffic brought on by the project, as well as explosives used in excavation, could decimate the Mekong’s remaining 85 endangered Irrawaddy dolphins.

It has called for suspension of the project “pending completion of independent, comprehensive and scientific trans-boundary studies,” adding that all additional studies should include transparent consultation with governments, civil society, and communities that would be affected by the proposed dam.

Laos’s announcement of plans to forge ahead with the Don Sahong in September 2013 also prompted objections from neighboring Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam, which said not enough study had been done on the project’s downstream impact.

An impact assessment carried out by Mega First claims that fish will be able to use other channels to migrate and that the dam’s environmental and social effects will be mitigated, but critics say that the study is based on flawed information.

Reported by RFA’s Lao Service. Translated by Somnet Inthapannha. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.