HANOI—Huu Loan, a Vietnamese poet best known for an autobiographical epic of love and the cruelty of war, has died at the age of 95 in his home village in the northern province of Thanh Hoa.

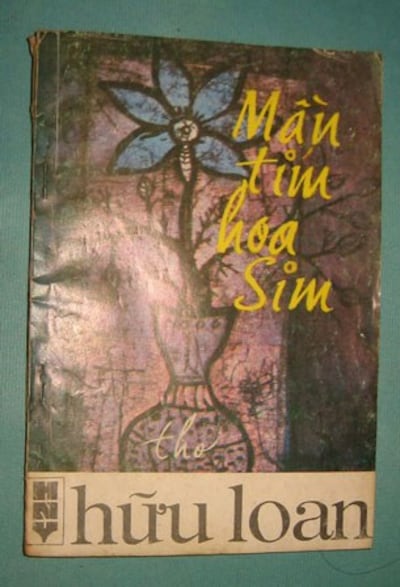

His most famous work, “The Purple Color of Sim Flowers” (in Vietnamese, “Mau Tim Hoa Sim”), describes a love story set against the background of war and conflict.

It became popular in both the Communist North and the U.S.-backed South during the Vietnam War (1959-75).

The poem was based on Huu Loan’s own love affair with his first wife, Nguyen Thi Ninh, and tells the story of a young Vietcong officer who learns of his young wife’s death when he passes through his home village on the way to war.

Witness to terror

Huu Loan served in Ho Chi Minh’s Communist army, and fought against the French from 1946-54.

He witnessed first-hand the terror of the Land Reform campaigns, in which hundreds of thousands of people accused of being landlords were summarily executed or tortured and starved in prison.

More than 172,000 people died during the North Vietnam campaign after being classified as landowners and wealthy farmers, official records of the time show.

Unofficial estimates of those killed by Ho Chi Minh’s Vietnam Labor Party, which later become the Vietnamese Communist Party, range from 200,000 to 900,000.

In the political rhetoric of the time, the victims were “dug to the core and destroyed to the root,” as enemies of the people.

Some were committed Communists, who cried out “Long Live the Communist Party” before being killed.

Official histories have since estimated that 71.66 percent of those who died were “wrongly classified.”

Happy second marriage

Huu Loan’s second wife, Pham Thi Nhu, was the sole surviving daughter of a family that was wiped out during the campaign to exterminate “landlords.”

When he found her in 1953, she was picking up trash to make a living.

Huu Loan’s response was to marry her and resign from the Party in a very public protest.

The result was many years of extreme poverty and social isolation, but relatives say the marriage was stable and happy, and the couple had a large family.

Huu Loan died peacefully while taking a nap on March 17, 2010. His daughter-in-law said. He is survived by his second wife, 10 children, and a dozen grandchildren.

Outspoken, always

A pillar of Giai Pham Magazine, Huu Loan acquired a reputation for speaking truth to power despite possible retaliation. In one essay he wrote:

"A variety of freedoms did exist even under the colonial regime. Let me list a number of memorable points in the French-occupied Vietnam that still remain in the memory of this slave ..."

"First, freedom of election. Most administrative offices were subject to popular vote. The provincial French officials simply played umpires. Other lesser [Vietnamese] officials dared not accept bribes. People could sue and even impeach officials. Corrupt officials were scorned by everyone."

"Second, freedom of the press and expression. Private individuals were allowed to set up their own papers. They refused to accept government subsidies ... [Third,] candidates to any position had to take qualifying exams. Those with talent would pass ... Workers' salaries were enough to pay for their living expenses and some for their savings."

"Students didn't have to pay tuition. Only higher education would cost them a few piasters a month. Good students were awarded scholarships, even scholarships to study in France."

"Sick people were given medicine at no cost at district dispensaries. Provincial hospitals had reserved areas for poor patients who received treatment and food for free. These hospitals were known as charity hospitals. Today, medical ethics have long disappeared. Hospitals everywhere take patients' money but offer no effective treatment."

"The French colonial regime was horrible indeed, but it is still a distant dream for people under regimes that are thumping their chests, bragging about independence [and turn around to oppress their own people]."

Original reporting and translation by Viet Long for RFA's Vietnamese service. Vietnamese service director: Khanh Nguyen. Executive producer: Susan Lavery. Written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.