Children picking through garbage, mothers begging in the streets,teenage girls forced into prostitution to help support their families.

I encountered poverty almost everywhere I went during a recent month in Burma.

International agencies estimate that one in three Burmese lives in poverty and one in 10 children dies before the age of five.

Garbage-strewn streets and polluted water are common where survival is a struggle and the government doesn’t seem to care.

Children, then dogs, pigs and rats pick garbage piles clean.

‘The government looks out for itself and its cronies and leaves the rest of us nothing,’ a village leader told me.

In the two biggest cities, Rangoon and Mandalay, I saw men, women and children sleeping on the streets, one woman below a tourist agency mural depicting the beauty of Burma.

Beggars are ubiquitous, especially at tourist stops. Tourists find it difficult to resist entreaties from mothers with filthy, half-naked children at their sides.

Burmese guides discourage foreigners from giving food or money, saying it only encourages others to beg. It has little effect.

Across Burma, children have dropped out of school to earn money. Everywhere I went, I saw children selling food and snacks on the streets or picking through garbage for something to use or peddle.

International agencies say the trafficking of young Burmese women in the Asian sex trade has increased dramatically. So has the number of women soliciting on the streets.

Women and children with buckets

The average worker makes little more than a dollar a day, or about $500 a year, in Burma. That’s the price of a leather golf bag in a shop popular with generals and businessmen in Rangoon. Beggars panhandle customers at a restaurant across the street.

This is a country where most people are without running water or reliable electricity--conveniences taken for granted in most of the western world.

Start with water. All across the countryside, from dawn to dusk, women and children with buckets, five-gallon jugs and other containers fetch water from rivers and ponds or, if their villages are lucky, wells or public spouts.

Waterborne diseases are rampant. A Burmese friend told me most people take diarrhea as a fact of life.

I visited a monastery on the shore of Inle Lake, a popular tourist destination. The toilets emptied into the water. The same is true for boat toilets on the nation’s rivers.

$4 a gallon for fuel

In Mandalay, sewage and garbage comingle in the rain gutters of the city’s main thoroughfare. On hot days, the stench is overpowering.

Remote villages dig holes for sewage and cover them when they are full.

Electricity is unreliable at best. When the power is out, generators provide electricity for those who can afford $4 a gallon for fuel to run them.

In Mrauk U, a city of temples being touted as a tourist destination, the electricity comes on two hours a day, 5 p.m. to 7 p.m. The new tourist hotels will have full-time generators. Not the people of Mrauk U.

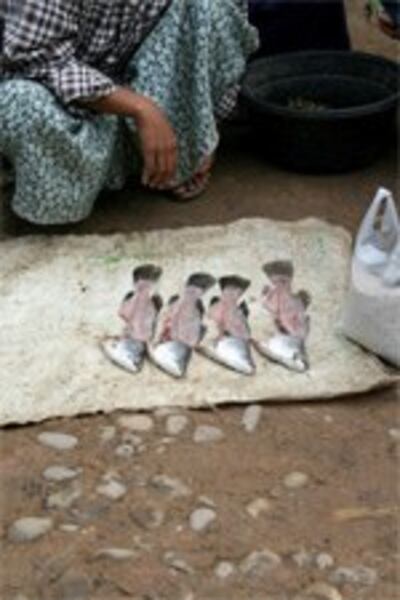

At a small market near Mrauk U, I saw a woman who had four small fish skeletons laid out on the street. She was trying to sell them to be boiled for fish soup. Pigs rifled through refuse on the street nearby.

Burma’s blessing—and the peoples’ salvation--is its rich agricultural bounty. It exports rice, but long ago fell from its ranking as the world’s No. 1 producer. Fish are plentiful.

Even so, the World Food Program estimates that one third of Burma’s children are malnourished.

I visited orphanages where children had been dropped off by parents unable to care for them.

‘It is so sad,’ my Rangoon friend said. ‘We are such a rich country with such human potential. It’s a crime the way we live.’

Unemployment in urban areas is estimated between five and 10 per cent. People who can’t find jobs turn to selling cigarettes, candy, old books, anything, on the street to help make ends meet.

Resentment swells

‘I often wonder what I would sell if I lost my job,’ a friend told me. ‘It keeps me up at night.’

As inflation eats into stagnant incomes, the resentment swells. It was the faltering economy and, specifically, a government increase in fuel prices that sparked the so-called saffron revolution last September.

‘It’s not over,’ another acquaintance told me. ‘We want better. Expect the unexpected.’

Tyler Chapman is a pseudonym to protect the author's sources.