by Dan Southerland

THLOK, Cambodia

It was near the Cambodian market town of Chipou on April 6, 1970, that the two now missing war photographers headed up this road, Highway One, on their motorbikes. The war in Cambodia had just begun.

Inexperienced in combat, the Cambodian army was rapidly retreating under pressure from well-organized North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces.

A Cambodian army colonel announced that this time, his army would not retreat. Instead, they would clear the highway up ahead, where we could see a Viet Cong roadblock—a burned-out, abandoned car in the middle of the road.

We were located about 10 miles from the Vietnamese border in the so-called Parrot’s Beak area, which juts into southern Vietnam.

I was working as a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor at the time. I had teamed up with Woody Dickerman of Newsday on this excursion into eastern Cambodia. We and many other journalists had been making almost daily trips to eastern Cambodia to "find the war."

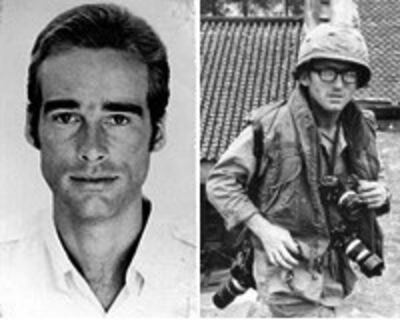

We met the two photographers, Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, in a small café in Chipou, where they were preparing to head up the road. Both were freelancers, known for taking risks.

Flynn, 29, tall and lean, the son of screen idol Errol Flynn, was on assignment for Time magazine. Stone, 30, short and nearsighted, was working for CBS News.

The two seemed to be in a light-hearted mood.

“This guy wants to get us captured,” said Stone, joking and gesturing toward Flynn.

The remark was hardly worth recalling, except for what happened next.

Just to the east of Chipou, I approached a Cambodian paratroop captain standing next to a jeep and told him that we intended to watch his troops clear the roadblock. He responded that they had no intention of moving up the road. They were pulling back.

Our driver, a small, wiry man who spoke both Vietnamese and Khmer and had a good sense of danger, immediately got into the Mercedes we had rented for the day and drove some 50 to 100 yards up the road to fetch Dickerman.

Dickerman stood next to a rice paddy taking pictures. The driver shoved Dickerman, a heavyset man weighing more than 200 pounds, into the Mercedes, spun the car around, and roared back to where I was located.

It was at that time that Stone and Flynn zipped up the road on their Hondas. A few minutes later, several French photographers drove back toward us, shouting that they had seen Flynn near the roadblock. He had shouted something about the “Pathet Lao,” or Laotian communists, being in the area. But in his excitement he was obviously mixing his words up and must have meant the Viet Cong were there rather than Pathet Lao.

The disappearance of Flynn and Stone had troubled me for years. How could two of the most experienced war photographers have driven straight into an ambush that they knew must be waiting for them?

After years of research Zalin Grant, a veteran war correspondent for Time magazine, was able to trace their movements after their capture. Grant concluded that the two had deliberately gone to see the war from the other side.

Based on interviews with several hundred former Viet Cong and Khmer Rouge soldiers, Grant discovered that after their capture the two were moved up the chain of command, first to the Vietnamese communist headquarters, located inside Cambodia near Mimot, then to Cambodia’s Kratie province.

The Vietnamese eventually turned the two, along with 10 other journalists, over to the Khmer Rouge, who killed them in late 1974 or early 1975.

Now I’m back in Cambodia with my Cambodian colleague Kem Sos, and we head up the now peaceful highway to see if anyone remembers Flynn and Stone.

At the spot on the road where the Viet Cong stopped Flynn and Stone, we chat with a couple of young Cambodians. They’ve heard the story of the two “foreigners” but say they are too young to know any of the details.

We move on to the village of Thlok, located on a bumpy, narrow dirt road two to three miles north of the highway. The Viet Cong were reported to have marched the two photographers up this road to the village, where they were interrogated.

At first, no one in the village seems to know anything. But one old man, Ek Phan, 78, recalls Flynn and Stone vividly. He remembers their red motorbikes. He accurately describes Flynn as tall and Stone as short.

While Flynn and Stone were moving up the highway, Ek Phan said, Cambodian villagers had shouted and waved to them to turn around but to no avail.

The last he saw of the two, their motorbikes had been taken away, and the Viet Cong were marching them across a rice field to the northwest of the village.

Others in the village, including several young Buddhist monks, show little interest in the story of Flynn and Stone. Indeed, being young and uneducated as to recent history, they seem to know little about what the murderous Khmer Rouge did to their country—or even their village and pagoda—once they took power.

A 24-year-old man named Yin, who identifies himself as the “abbot” of the pagoda, talks instead of a need to get donations for a pagoda school. He’s wearing a strong perfume, which offends Sos.

We decide that it’s time to leave this village, whose residents have seen so much that they would like to forget.