By Dan Southerland

Testimony at the Khmer Rouge Trial now under way in Phnom Penh has stirred memories for me of the Cambodian War.

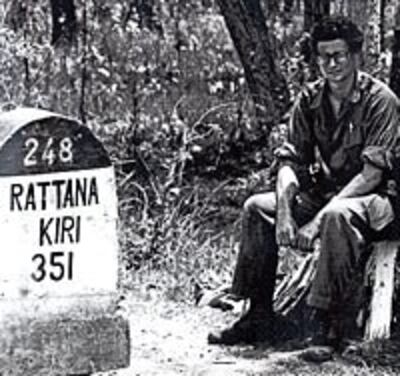

I remember in particular chatting with two American photographers moments before they drove up a road on motorbikes early in the Cambodian war, never to come back. Sean Flynn and Dana Stone wanted to see the war “from the other side.”

I thought that what they had done was reckless, given that they knew they were heading for a Viet Cong roadblock. But with time I’ve grown to understand a bit better why they would do such a thing.

First, it was a given that the photographers were always out in front of us reporters. They had to be near the action. Second, I've started making a list of all the reckless things I did as a reporter for The Christian Science Monitor both in Vietnam and Cambodia. And, sure enough, I can recall several times when I took what many might regard as really stupid risks.

Flynn and Stone disappeared on April 6, 1970. That was 39 years ago. So friends and even my wife sometimes understandably express surprise that I can’t seem to put such events behind me.

But the Cambodia “genocide tribunal” reminds me that as far as we know, the Khmer Rouge killed almost every reporter, photographer, TV cameraman, or Cambodian co-worker whom they captured.

The total number of foreign journalists, photographers and cameramen lost over a five-year period comes to 26, and that does not include our Cambodian colleagues.

Some are still listed as “missing,” but they’re presumed to have been executed or to have died from disease while in captivity.

I know of one exception. Dith Pran, whom I employed briefly as a translator and "fixer" in 1970 and who went on to work for Sydney Schanberg of The New York Times, survived the Khmer Rouge by passing himself off at a checkpoint as a semi-literate taxi driver.

He suffered through life in a Khmer Rouge work camp, but at least he was not executed.

First at the scene

For years now, I've put off looking at a beautiful but terrifying book called Requiem, dedicated to the work of 135 photographers from all sides of the wars in Indochina who are recorded as missing or having been killed.

The photos displayed in the book, edited by photographers Horst Faas and Tim Page, serve as a reminder that the photographers moved far ahead of us in the jungle, on the hilltops, and on the roads. A reporter could arrive at the end of a battle and reconstruct the event. The photographers could not. They had to be there.

In Requiem, veteran war correspondent Jon Swain describes the new challenges posed by Cambodia for both reporters and photographers who had covered Vietnam.

“In Vietnam the helicopter, the workhorse of the U.S. Army, was the journalists’ taxi ride to the fighting; in Cambodia, where the Americans were not on the ground, the war could be covered only by car.

“This led to a type of danger unencountered in Vietnam … In Cambodia, journalists had no choice but to fend for themselves.

“The rule was to not be the first to travel down the roads in the early mornings because of the land mines and to never be on them after 4 p.m., when it began to grow dark, the peasants left their fields, the government soldiers retreated to their camps, and the Khmer Rouge took over.

“It became so dangerous that after a while the main Western news media forbade their staff photographers to go out into the field and paid local Cambodians to cover the fighting for them.”

No reporter whom I knew at the time went into the field on his own. We always teamed up with other reporters and took a Cambodian with us who could act both as an interpreter and a “fixer.” I avoided working with photographers because of the risks they took.

Death on the highways

But I knew a few of the photographers. One of them was Francis Bailly, a freelancer for Gamma and UPI who was among the gutsiest. He was known for spending long periods with Cambodian troops in the field.

In February 1971, Francis’s body was found in a taxi on Route 7, where Cambodian troops had been ambushed by Khmer Rouge guerrillas. According to Requiem, he had been shot, execution style, in the back of the head.

Everyone who had worked for UPI, as I had, also knew Kyoichi Sawada, a Pulitizer Prize-winning photographer. Sawada was killed in October 1970, south of Phnom Penh, along with UPI bureau chief Frank Frosch. Both men had been shot several times through the chest.

Neither was armed, and both were dressed in civilian clothes.

In a new edition of his book Two of the Missing, Perry Deane Young eloquently explains what all of us—correspondents, photographers, and TV cameramen—had in common. It was the thrill of covering a war, seductive and easy to understand for those who were there, but hard to explain to those who were not.

Young, who was a Vietnam reporter and close friend of Sean Flynn and Dana Stone, provides the context needed to understand why the two went up that road never to be seen again.

And finally, he forcefully argues that the still pictures taken by photographers such as Flynn and Stone will have more lasting impact than many of the words we wrote.

See also:

Dan Southerland's Cambodia Diary 2: "War from the Other Side" and Dith Pran dies at 65