Cambodia’s most prominent charity has taken more than $7.2 million in donations from companies and individuals linked to cyberscam sites and human rights abuses since 2020, an RFA investigation has found.

The Cambodian Red Cross, a member of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies network, or IFRC, is well-known across the country for responding to natural disasters and its work against HIV/AIDS. But the organization has also been closely intertwined with Cambodia’s ruling family for decades and has previously been accused of leveraging aid for political purposes.

Now after years of warnings about the CRC’s political entanglements, its use for reputation-building among Cambodia’s elite appears to have extended to those allegedly connected to Cambodia’s thriving human trafficking industry.

A scroll through the Cambodian Red Cross Facebook page showcases dozens of posts thanking groups with documented ties to cyberscams for their donations. Some have given large sums year after year, while others have given more sporadically. Donors have ranged from high-profile businesspeople — some of whom have been sanctioned by Western governments for known trafficking and criminal involvements — to up-and-coming individuals allegedly associated with scam centers.

It’s not uncommon for wealthy people around the world, including those facing notoriety, to donate to philanthropic causes. But in Cambodia, experts interviewed by RFA say the donations fit into the government’s practice of using patronage and public spending to cover wrongdoing.

Such donations have the impact of painting alleged criminals in a positive light to citizens, while also currying favor with the ruling party, said Jacob Sims, an expert on the Southeast Asian human trafficking crisis.

“It’s abundantly clear that the CRC is only one of many different mechanisms for elite patronage being paid into a profoundly corrupted system,” Sims told RFA.

In response to RFA’s questions about the IFRC’s oversight of national Red Cross societies, the federation said it “takes seriously any credible allegation of violation of the integrity policy,” including mismanagement of funds, fraud and corruption and abuse of authority, but that it cannot “speculate on violations or investigations” of national societies without further review.

The CRC did not respond to questions about its process for reviewing donations or whether it was aware of reports about alleged criminal activity of its donors.

Extension of the ruling party

For more than three decades, the CRC, which was established in 1955 and became a member of the IFRC in 1960, has been closely intertwined with Cambodia’s ruling family and those in its orbit.

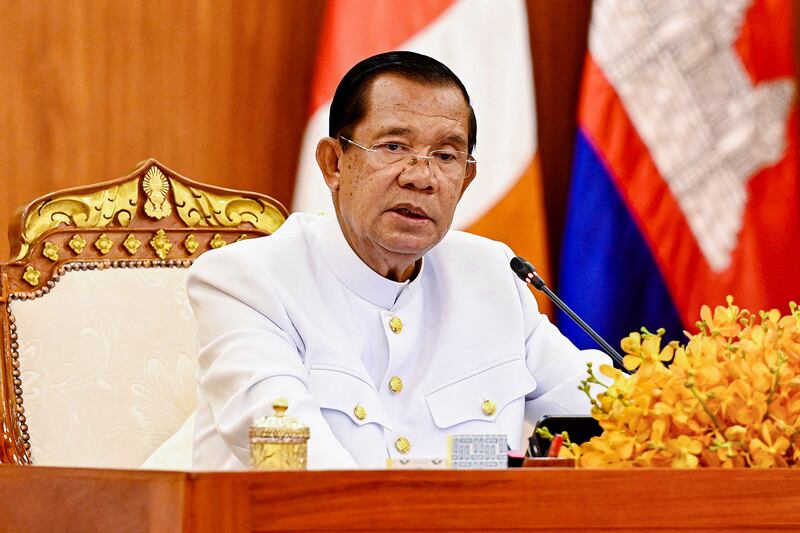

As former Prime Minister Hun Sen began consolidating power in the early 1990s, prominent tycoons, or oknhas, donated large sums to the CRC “to maintain access to the political elite and, in return, gain protection or favors for their businesses,” said Sophal Ear, a Cambodia expert and professor at Arizona State University’s Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Over time, the relationship between the CRC and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party has become so close that “the CRC is perceived as an extension of the CPP,” Ear wrote in an email.

Today, Hun Sen’s wife, Bun Rany, serves as the organization’s president, with several former and current politicians and their relatives joining her on the leadership team. Some of the officials have long been dogged by allegations of criminality. CRC Vice President Choeung Sopheap, for example, who is one of Cambodia’s most well-connected tycoons, has been caught up in accusations of illegal logging and mass evictions for years through several of her family companies, accusations she has not publicly addressed. (The CRC did not respond to requests for comment.)

In 2013, as discontent with Hun Sen’s rule peaked, opposition leaders accused the organization of using aid as political strategy: providing no relief to families of people killed or injured by state security forces during mass anti-government protests even as the CRC raised $35,000 to help injured guards, according to reports at the time. That same year, while speaking at a Red Cross event, Bun Rany told families that had been hit by a flood “there is no other party coming to help you here … there is only the CPP.”

RELATED STORIES

Cambodia’s Prince Group: A business empire built on crime?

EXPLAINED: What are scam parks?

Cambodia’s new cabinet is steeped in nepotism

Today, businesspeople view the organization as a “conduit” for the ruling party, according to a longtime executive in Cambodia, who asked for anonymity for safety reasons. Annual donations are “understood that it’s something we have to do, if you want to stay in good graces and continue doing business,” he said.

The executive has worked in multiple industries, including mining, which is a common source of funds publicized by the CRC, along with hydropower and gambling companies.

“We were expected, for every concession or license that we had, we’d donate $20,000 to the Red Cross,” the executive said. “All the people we knew in the industry, it was just a given.

“This donation is actually much more comfortable than something that’s behind closed doors, like the envelope under the table, for example,” he said. “You get a certificate of appreciation [that] this was an official donation from your company to the Red Cross. … I’d much rather have it that way.”

Sanctioned donors

Starting around 2020, foreign embassies, journalists and NGOs began to document a rapidly growing industry across Cambodia: Thousands of workers were trapped inside heavily guarded compounds and forced to scam people online, often under threat of torture or beatings.

Over the next four years, the industry grew to encompass an estimated 100,000 victims in Cambodia alone. And while the Cambodian government has often claimed that the size of the industry was exaggerated, it responded to international pressure with high-profile crackdowns and promises to prosecute perpetrators.

At the same time, the CRC appeared to benefit financially from the web of companies and people allegedly connected to such schemes.

Each year in the weeks around May 8 — the annual World Red Cross and Red Crescent Day — the CRC typically posts a stream of thank-yous for individual donations on its Facebook page, naming the donor and the amount given. Some large donations are also touted on state-aligned media FreshNews or other outlets.

Notable repeat donors from the past four years include Chen Zhi, the chairman of Prince Group, who gave more than $2 million to CRC between 2021 and 2024. RFA previously reported that human trafficking and forced scamming — including torture — have been witnessed at Golden Fortune Science and Technology Park, a Prince-built compound.

Prince has strenuously denied any involvement with human trafficking. In a statement to RFA, Prince’s chief communications officer, Gabriel Tan, reiterated previous public statements about RFA’s reporting, including that “PHG does not own or manage the referenced compounds … and is not involved in any of the alleged activities conducted therein.

“Many Asian businessmen are philanthropists who contribute to their community,” Tan said.

Other CRC donors include Try Pheap, a U.S.-sanctioned tycoon who has given $300,000 a year since 2021; Li Tao, a Chinese businessman who is sanctioned by the U.S. for rights abuses and who has given $1.9 million over four years; and Chen Al Len, the director of K.B. Hotel, a notorious human trafficking site sanctioned by the United Kingdom, who has given $10,000 and $100,000 on separate occasions since 2021.

Try Pheap, the chairman of the board of directors of a special economic zone in Pursat province, has been sanctioned by the U.S. since 2019. Starting in 2021, Chinese and other foreign trafficking victims reported being held against their will inside the SEZ and forced to perform online scamming.

The U.S. sanctioned another prominent Cambodian in September 2024, accusing Sen. Ly Yong Phat — who is also president of the Cambodian Oknha Association — and his companies of “serious human rights abuses” at scam compounds such as O’Smach Resort, where victims said they were electrically shocked and beaten. Ly Yong Phat has also been connected to multiple compounds in Koh Kong province, where he has a history of controversial sugar plantations.

In the last two years, Ly Yong Phat has individually given at least $640,000 to the CRC, RFA found, including $20,000 directly to the CRC’s Koh Kong branch. He separately facilitated joint donations from the Cambodian Oknha Association totaling nearly $3 million.

Try Pheap, Li and Chen could not be reached for comment. Ly Yong Phat also could not be reached for comment, though the Cambodian government has previously denied trafficking allegations on his behalf, calling U.S. sanctions “politically motivated.”

Other donors with documented ties to scamming have given one-off donations, including the Jin Bei Group, which gave $20,000 in 2024, the same year dozens of trafficked victims were released from one of its properties in Sihanoukville. Jin Bei Group has been linked to multiple human trafficking cyberslavery compounds in Cambodia. A foundation associated with the Zheng Heng Group, which has been sanctioned by the United Kingdom over scamming allegations, gave $100,000 in 2024.

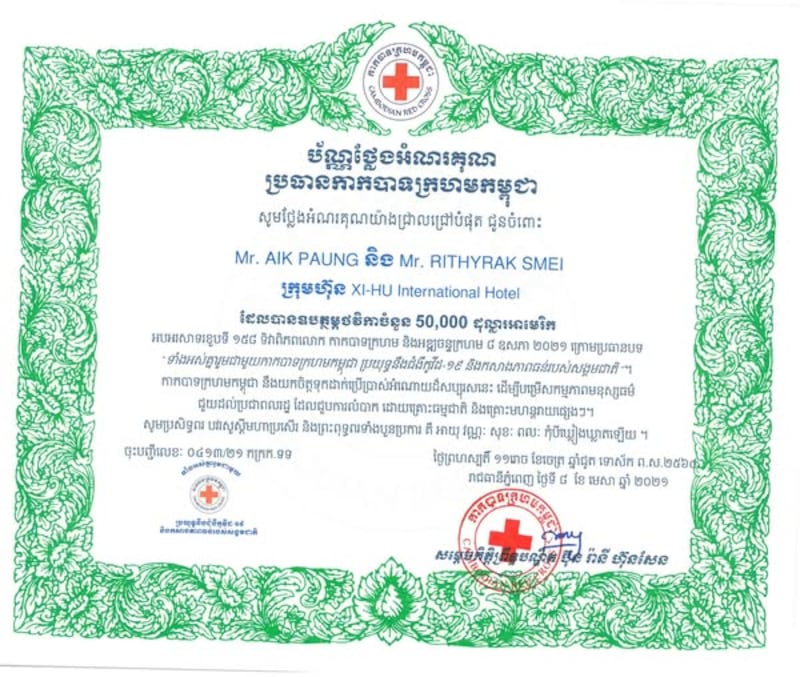

Lesser known alleged scammers have also donated. Aik Paung, a Myanmar-born businessman and naturalized Cambodian citizen, donated at least $140,000 since 2020. Over the same period, local and international media outlets documented scamming at a Sihanoukville hotel operated by a company where Paung was a director until early 2025, with at least two Chinese nationals reportedly falling or jumping to their deaths.

The Cambodian government has repeatedly said it would crack down on scams. The CRC did not respond to multiple queries from RFA over whether it was aware of the allegations of crimes against its donors, how it vets donations or how it deals with money potentially sourced from criminal activities.

A global body with limited oversight

The IFRC — which does not manage its 191 national societies — has limited investigatory powers.

In 2016, watchdog Global Witness called for the organization to expel the CRC as a member, referring to it as a “microcosm of Hun Sen’s patronage system.” The IFRC did not appear to respond publicly at the time; when asked by RFA whether it investigated the allegations, the organization said it “[doesn’t] comment on historical cases that were not previously shared with the public.”

In response to RFA’s findings about donations to the CRC, the IFRC said in an email it would “engage with the Cambodian Red Cross to get information and clarification” but emphasized that national societies “have their own internal mechanisms to address issues of integrity and disciplinary measures.”

Allegations of breach of integrity related to funding “are dealt with in the country by the National Societies,” the organization wrote.

“In the event that allegations reach the [IFRC] we offer support to National Societies to carry out an independent investigation,” it added. The organization operates an “integrity line” for whistleblowing that received 365 reports in 2023 related to fraud, corruption or sexual misconduct.

The IFRC’s national societies, of which there can only be one per country, vote in the organization’s General Assembly and may receive development support and funding. In the last five years, the organization has provided 259,692 Swiss francs, or about $286,000, to the CRC, the IFRC said in its statement.

While the International Committee has a strong reputation for its neutrality, the degree to which national Red Cross societies are entangled with politics varies widely around the world, Dorothea Hilhorst, a professor of humanitarian studies at Erasmus University Rotterdam, told RFA.

Societies are intended to be independent from, but also auxiliary to, their national governments, creating a “very narrow, difficult balancing act.” Other chapters around the world have received criticism for appearing to meddle in politics, most recently in Russia, as well as alleged corruption practices.

“The more politicized the country, the more politicized the Red Cross,” Hilhorst said.

‘A larger problem’

RFA could not determine how much money the CRC has received in total since 2020, nor whether the donors behind the $7.2 million had given more than was publicly advertised, because the organization does not release regular public financial reports or summative donor lists. An audit document submitted to the IFRC indicated the organization had received a combined roughly $29.8 million in donations from 2022-2023, with nearly $170 million held in three banks.

Meanwhile, alleged criminal activities linked to the scam industry continue unabated, with the reported expansion of compounds across Cambodia and Southeast Asia.

Phil Robertson, director of the Asia Human Rights and Labor Advocates Consultancy, said donations tied to such operations have “seriously undermined” the Red Cross movement.

“While these may look like voluntary donations by rich people, with a formal thank-you and all that, these donors are directly connected to criminal scamming enterprises,” Robertson told RFA.

“Scamming is a larger problem beyond Cambodia, and a global movement like the Red Cross should have a position on this. These groups are causing damage on a global scale.”

Edited by Boer Deng and Abby Seiff.