King Norodom Sihamoni has approved a law that allows prosecutors to bring criminal charges for denying the existence of crimes committed during Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge period.

Those who “deny, trivialize, reject or dispute the authenticity of crimes” committed during the regime’s rule face between one and five years in prison and fines from 10 million riel (US$2,480) to 50 million riel (US$12,420) under the law, which the king signed on March 1.

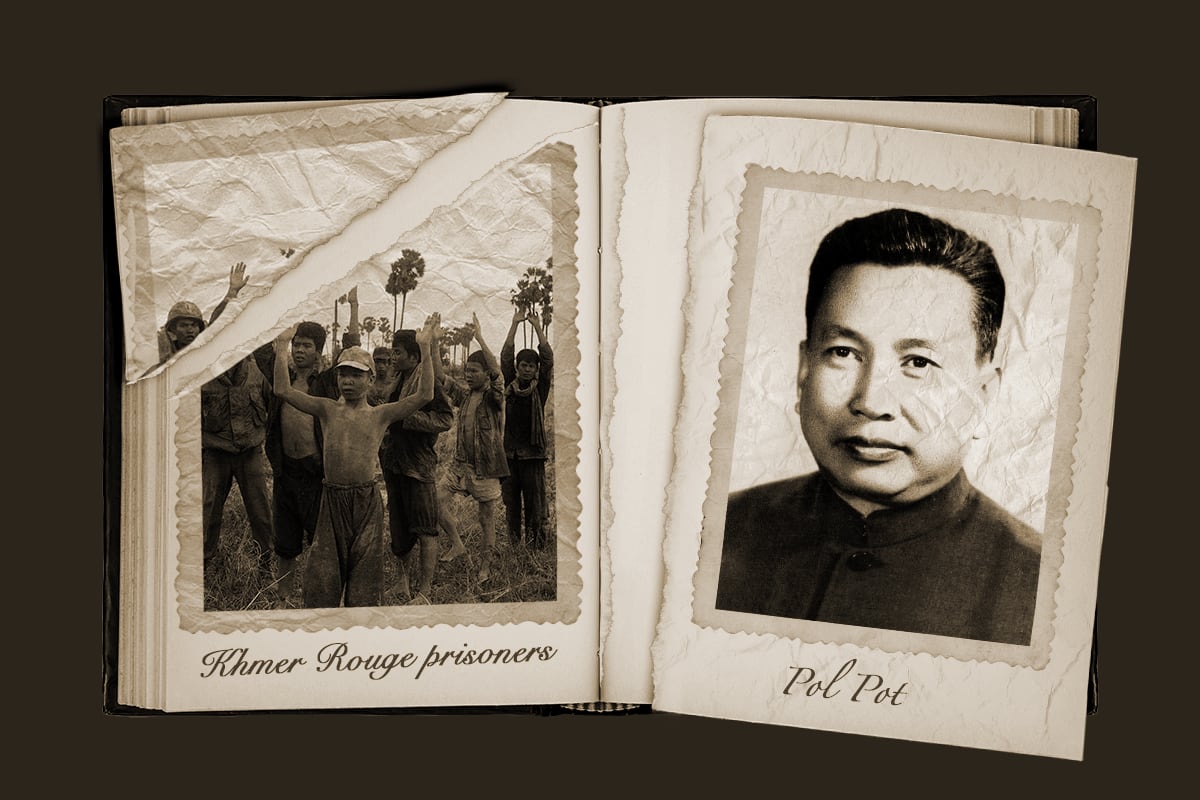

The Khmer Rouge regime was responsible for the deaths of more than 1 million people from starvation, overwork or mass executions between 1975 and 1979.

The law was requested last year by Hun Sen, the former prime minister who handed power to his son in 2023. It replaces a 2013 law that more narrowly focused on denial of Khmer Rouge crimes.

It was unclear why Hun Sen initiated the measure. But he made the request to the Council of Ministers in May 2024 — the same month that he called for an inquiry into disparaging social media comments about him that were posted on TikTok and Facebook in Vietnamese.

Some of the comments read: “Vietnam sacrificed its blood for peace in Cambodia,” and “Don’t forget tens of thousands of Vietnamese volunteers who were killed in Cambodia.”

Hun Sen was a Khmer Rouge commander who fled to Vietnam in 1977 amid internal purges. He later rose to power in a government installed by Vietnam after its forces invaded in late 1978 and quickly ousted the Khmer Rouge regime.

Vietnamese forces remained in Cambodia for the next decade battling Khmer Rouge guerrillas based in sanctuaries on the Thai border.

Ideas and statements

Human rights activists have criticized the law as divisive and have warned that it could be used to stifle criticism of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, or CPP, which has historical ties to Vietnam.

For Hun Sen and the CPP, the Vietnam-led ouster of the Khmer Rouge was Cambodia’s moment of salvation, according to opinion writer David Hutt.

“For today’s beleaguered and exiled political opposition in Cambodia, the invasion by Hanoi was yet another curse, meaning the country is still waiting for true liberation, by which most people mean the downfall of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) of Hun Sen and his family,” he wrote for Radio Free Asia last month.

But it’s not the government’s proper role to mandate a version of history, said law and democratic governance expert Vorn Chan Lout. Being punished for ideas and statements that differ from those in power is something that also occurred under the Khmer Rouge, he added.

“This doesn’t reflect a country that has advanced ideas and views,” he told RFA.

The law was approved by the Council of Ministers in January. The National Assembly and the Senate, where Hun Sen now serves as president, gave its unanimous approval in February.

Last month, the Ministry of Justice criticized Hutt’s opinion article, noting that at least 17 European countries have similar laws that criminalize Holocaust denial or the denial of other crimes against humanity.

Some of those laws allow for penalties of up to 10 years in prison, the ministry said in a Feb. 18 statement.

“Cambodia’s legislation is not an exception, but rather a necessary step to preserve historical truth and protect social harmony,” it said.

“The denial or glorification of these crimes is not an exercise of free speech,” the ministry said. “Such actions constitute a profound insult to the memory of those who perished and inflict renewed pain upon surviving victims and their families.”

Translated by Yun Samean. Edited by Matt Reed.