Chinese officials remain tight-lipped about how they plan to carry out diplomacy with the United States while America’s top diplomat, Marco Rubio, remains officially sanctioned for critical comments he made about Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs and Hong Kong in 2020.

Rubio, formerly a Republican senator from Florida, was hit with retaliatory sanctions for “interfering” in China’s domestic affairs by criticizing its 2019 crackdown in Hong Kong and what the U.S. government calls a “genocide” against ethnic Uyghurs in the far northwestern Xinjiang region.

Under China’s Anti-Foreign Sanctions Law, that puts Rubio on a travel ban list, potentially complicating U.S.-Chinese diplomacy.

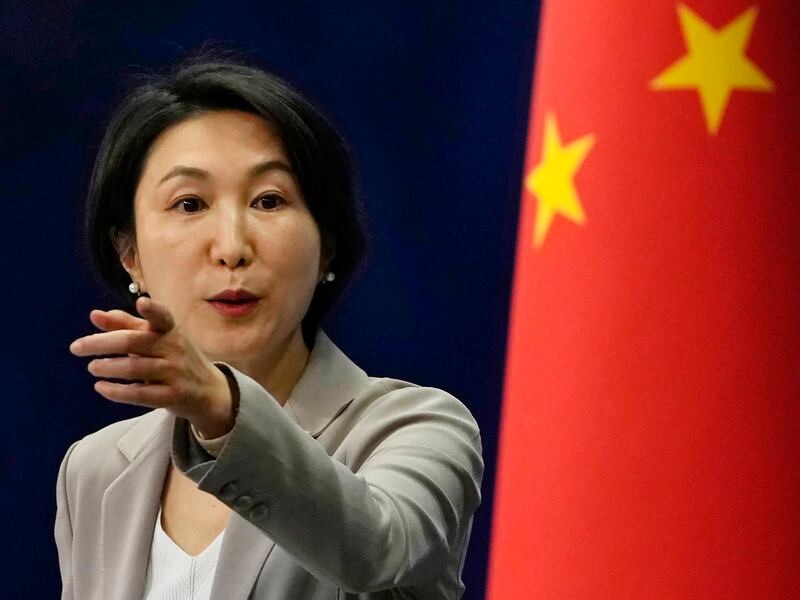

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Mao Ning was ambiguous at a briefing on Thursday when asked whether Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi would speak with Rubio by telephone given the sanctions.

“I have no information to share on your question,” Mao said, before adding that Beijing still thought engagement was important.

“Let me say more broadly that it’s necessary for high-level Chinese and U.S. officials to engage each other in appropriate ways,” she said. “In the meantime, China will firmly defend its national interests.”

On Monday, Rubio was confirmed as U.S. President Donald Trump’s secretary of state after stating at his Senate confirmation hearing that he believes China is the “biggest threat” to America’s security.

He also nodded to his fraught ties with China during the hearing.

“Indeed, I’ve been strongly worded in my views of China,” Rubio said. “Let me just point out they’ve said mean things about me too.”

What’s in a name?

In the aftermath of his confirmation, Chinese official state documents referring to Rubio appeared to change the Chinese characters used to transcribe his name, leading to suggestions Beijing might be attempting to skirt the sanctions and travel ban by renaming Rubio in Chinese.

However, the Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson seemingly put the kibosh on that account at an earlier press briefing Wednesday, telling a reporter she was “not yet aware” of his name being written differently.

“If you ask me, instead of how his name is translated in Chinese, it’s his actual name in English that is more important,” Mao said. “What I can tell you is that China’s sanctions are aimed at the words and actions that harm China’s legitimate rights and interests.”

RELATED STORIES

Beijing changes Rubio’s Chinese name, perhaps to get around travel ban

Rubio says US at risk of relying on China

China Levels Retaliatory Sanctions on US Officials Over Xinjiang Measures

Trump says China tariffs could begin Feb. 1

The Chinese Embassy in Washington was also opaque when asked by Radio Free Asia about the sanctions, travel ban and name change.

“China will firmly defend national interests,” spokesperson Liu Pengyu said. “In the meantime, it’s necessary for high-level Chinese and American officials to maintain contact in an appropriate way.”

The U.S. State Department told RFA only that Rubio did “not have any travel to announce at this time.” It otherwise declined to comment on the sanctions and the new secretary’s apparent Chinese name change.

“Secretary Rubio looks forward to promoting American safety, security and prosperity through his engagements with China and other countries throughout the region,” a spokesperson said.

Sanctions diplomacy

It’s not the first time sanctions have complicated U.S.-China ties.

From March to October 2023, Li Shangfu served as China’s defense minister while subject to U.S. sanctions issued in 2018 for purchasing banned Russian missile systems when he was a lieutenant general.

Li’s tenure came at a nadir for U.S.-China ties and saw the Chinese defense minister and the rest of China’s military refuse any direct contact with their American counterparts, leading to public complaints from then-U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin in June 2023.

But Li was sacked by President Xi Jinping in October 2023 –- and later expelled from the Chinese Communist Party altogether –- a month before Xi and then-U.S. President Joe Biden’s summit in San Francisco, where military-to-military contact was re-established.

Edited by Malcolm Foster.