HONG KONG—Two award-winning authors who exposed corruption, mistreatment, and hardship faced by China’s 900 million peasants amid the country’s much-touted economic miracle say they are planning a sequel to their groundbreaking first book.

"We have made a decision to concentrate on writing about the countryside for at least the next five years," said Wu Chuntao, who co-authored The Situation of China's Peasants with husband Chen Guidi.

“We are probably not going back to Anhui, but we will continue to write about China’s rural communities in other places all around the countryside. We will be looking for continuing problems among farmers, and for their solutions—what the farming communities are doing to address these problems,” Wu, 44, told RFA’s Mandarin service during a recent U.S. visit to attend a literary festival.

“We expect to go to a few of the inland Western provinces. If we can get the material we need, we would expect to produce this book by next year,” she said.

Born to farming families

We expect to go to a few of the inland Western provinces. If we can get the material we need, we would expect to produce this book by next year.

Chen and Wu, who were born to peasant families in Anhui and Hunan, use journalistic methods to gather stories from China’s rural communities, but what they produce is book-length reportage.

Both authors are members of the Hefei Literature Association and have received awards for their work, including a nomination for the Lettre Ulysses Award for Reportage 2004. Chen, 62, has won the prestigious Lu Xun award for literature.

They spent around U.S.$20,000 of their own money to produce their best-known book, which was debated and praised across Chinese Internet chatrooms and bulletin boards once it began appearing in extracted form in the journal Contemporary Age. It also spawned a protracted libel suit from one of the officials named in it.

They described a life spent traveling from one poverty-stricken household to the next, persuading frightened and disillusioned farming families to tell their stories, constantly on the lookout for local officials who might harass or detain them.

Chen said: “Both Chuntao and I have the attitude that all the farmers we interview are in fact our mothers and our fathers, our relatives. As their children, we are trying to give voice to their grievances. Because they don’t have a voice, they need an advocate.”

He said the couple often faced the attitude that simply telling the authors a story of official oppression would do nothing to solve the problem.

Fear of official harassment

“If we have been talking for a long time, they will offer us something to eat—they are very courteous. But we usually take them to dinner. We don’t take them to posh, fancy restaurants, but rather to smaller eateries on the outskirts of the village or township,” he said.

“Firstly, we can’t afford to do that, and secondly those aren’t their usual stamping grounds. So we always eat in rather grubby, scruffy surroundings, and we always order the dishes that they like to eat. Sometimes the meat in those places is the size of a mah jong tile, and still has the hair of the animal on it,” he added.

“When we were researching the book about the Huai river we were running about like crazy. We visited 46 different cities in the region. We are talking about a rural population that is 40 percent of the entire population of the planet,” Chen said.

Wu said the pair tried to be as unobtrusive as possible.

“Initially we go to visit the farmers as if we were visiting family. Often the local officials don’t even know we’re there. But sometimes they discover us. We can tell... [perhaps] a different car arrives in the village and a stranger appears. What we usually do then is to take our interviewee with us to a different place, a different province or city, and carry on the interview there.”

“Or we find a place that’s equidistant; we once stayed three nights at a bathhouse in Hubei and the local farmers’ representatives came and stayed there too and told us their story. Sometimes they can take us back to their village so we can take a look, but we couldn’t actually do any real talking there,” she said.

Telling their stories

Eventually, the people they are with begin to see the point of what they are doing, and open up, the couple said.

“We just pour the beer into big bowls and slurp it back and eat with the same chopsticks they do,” Chen said.

“They relax then and they begin to see us as one of them—as people who are simply hearing their story, and after a while they are quite moved and say we are listening to them tell their story, and they don’t care so much whether or not we can actually do anything to help them with their problem. We got the vast majority of our stories in this way,” said Chen, who named his role models as Chinese writers Lu Xun and Liu Binyan, both revered for their role in describing social injustice in modern China.

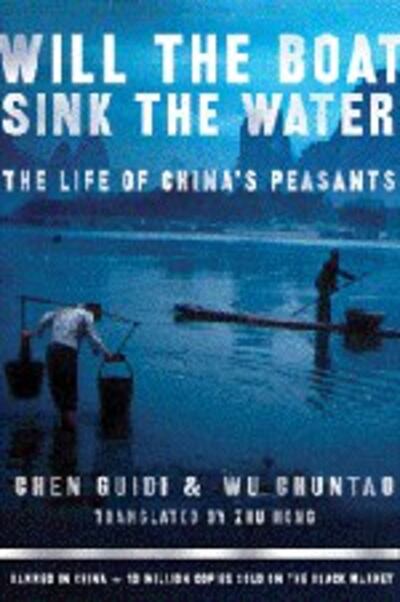

The English-language edition of their book was published in the United States in June 2006 by Public Affairs Books, under the title Will the Boat Sink the Water? The Life of China's Peasants.

Original reporting in Mandarin by Bai Fan. RFA Mandarin service director: Jennifer Chou. Translated and written for the Web in English by Luisetta Mudie. Edited by Sarah Jackson-Han.