It looks like Hun Many, the younger brother of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet, wants more attention.

Last August, his brother inherited the prime ministership from their father Hun Sen, who had been in the job for close to four decades. At the same time, Hun Many, a parliamentarian since 2013, was made minister of civil service, usually an unprestigious position, during a vast government reshuffle in which many of the graying, first-generation party leaders resigned and handed over power to their children.

Yet, there are suggestions that Many wanted more prestige.

The National Assembly voted unanimously on Feb. 21 to appoint Many as a deputy prime minister. He received all of the 120 votes during an extraordinary session.

There are 10 other deputy prime ministers, so Hun Sen’s youngest son became the 11th deputy prime minister.

Pro-government media trumpeted the elevation of the youngest deputy prime minister in history. One particularly sycophantic article declared: "At 41, Many symbolizes a generation of leaders increasingly taking center stage globally, equipped with a blend of traditional wisdom and contemporary insights… As Cambodia stands on the brink of this noteworthy transition, the story of Hun Many's rise to one of the country's highest offices is a compelling narrative of heritage, ambition, and the promise of a new era."

He was also front and center in the ruling party-linked newspapers this month in condemning a duo of Taiwanese youths who had made a fake video claiming to have been kidnapped in Cambodia. Echoing his father's indignant patter more closely than Hun Manet typically does, Many vowed: "These acts gravely damage the Kingdom's honor and image. We will not tolerate them. May this never occur again."

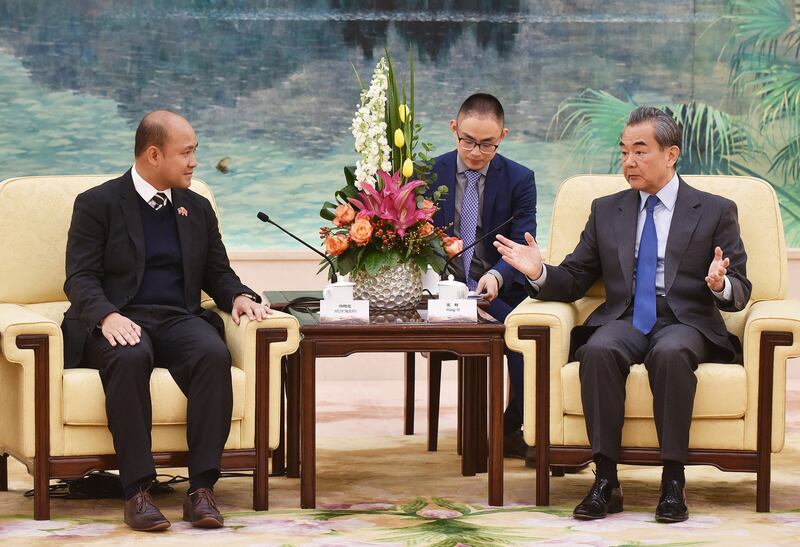

He has also been in the newspapers and social media over the past month, perhaps by design, talking about education and bureaucratic reform. Last month, he met with the EU ambassador, Igor Driesmans, to discuss civil service reform, and with a visiting Chinese delegation led by Li Shulei, head of the Publicity Department of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee.

But the question is worth asking: Why wasn’t Hun Many made a deputy prime minister last August when these ranks underwent a major reshuffle? Several of his young-ish peers were appointed deputy prime ministers at the time, including Sar Sokha and Tea Seiha, who also took over as interior and defense ministers, respectively, from their fathers.

One explanation is it was never part of the succession plan for him to be a deputy prime minister. Indeed, he’s slightly an odd fit for this role. Aside from Sar Sokha and Tea Seiha, the 10 current deputy PMs are either older, ministerial technocrats (Aun Pornmoniroth, Vongsey Vissoth, Sok Chenda Sophea, Sun Chanthol, Hang Chuon Naron) or Hun Sen loyalists (Neth Savoeun and Keut Rith).

Family in charge

Maybe Many could be said to sit in both camps, but the appointment seems forced. It isn’t part of a wider reshuffle. The only other appointments made during the same National Assembly special session were Sry Thamarong and Pen Vibol, currently ministers attached to the prime minister, who became senior ministers responsible for special missions.

However, the timing probably isn’t coincidental. Hun Sen, his father, will be named the new Senate president later in the month, a post that will make him acting head of state when King Norodom Sihamoni is out of the country. Strictly speaking, there is no reason why Hun Sen needs to take that position; he has the institutional power to dictate politics from behind the scenes.

Thus, the only logical reason is that Hun Sen thinks he needs to become Senate president, perhaps as another show of force to the rest of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) that his family is well and truly in charge.

If that's the case, making his son a deputy prime minister days earlier makes sense symbolically. Then again, it might also be a move to absolve any jealousy emanating from Hun Many. Who knows if he found it grueling to hear his father say this last year: "Manet has the highest level of education among [my] children and has received the most love and respect from the people."

And not only has his elder brother gone straight from the military to becoming prime minister without having ever served in a political office before (unlike Hun Many), Hun Manet was also named a CPP vice president in December.

At the same time, though, Hun Many as well as some other princelings – Sar Sokha, Tea Seiha, Peng Ponea and Say Sam Al – were appointed onto the party’s Permanent Committee (or Politburo), its elite decision-making body.

Tensions between the Hun brothers have long been a source of gossip in Phnom Penh, so much so that Hun Sen has occasionally brought it up without prompting during his lengthy diatribes. In September 2022, Hun Many publicly denied accusations made by the exiled analyst Kim Sok that there were tensions between himself and his brother over who would succeed their father.

He dismissed it as "ridiculous," although Hun Sen was a little more philosophical and revealing. "If your family is dirty with jealousy between brother and sister, husband and wife, that's your family," he said. "But my family has hierarchy and my son listens to his brother, he has no ambition to be prime minister instead of his brother."

Hun Sen returned to the same topic last August, just before the succession handover. “My two other sons, Manith and Many, would not accept any position that is higher than Manet.

That is the truth," he said, referring also to Hun Manith, who is head of military intelligence and, since last year, deputy army chief.

With his usual plain-speaking wit, he added: “[If] the eldest child is addicted to drugs or is unable to do anything, [then] the job is given to the second or to the third child.”

But commentators have some reason to think that Many has always vied for the top job. In a radio interview in 2015, Hun Many stated that "Becoming prime minister is my intention as well as [the intention] of other young people.''

That caveat might have been intentional to give him deniability. After all, what politician doesn’t dream of taking the top job? An attempt at hagiography for Many – the book “Hun Many’s Hope,” written by Leang Delux, – was published last year. But there is nothing like the cult of personality confected for his brother.

Well-oiled outfit

While there may be some jealousy at play, it was always unlikely that Manet, as the eldest son, would be passed over, not least because he had been tapped to succeed his father for more than a decade. The Hun clan is a well-oiled and hierarchical outfit, as Hun Sen noted, with each of the children and extended family put in control of important industries or state institutions. Cambodia might be denied such a privilege, but there is a separation of powers – or, rather, a divvying up of responsibilities – within the Hun family.

Indeed, Many is far from being the spare to his brother. He runs the Union of Youth Federations of Cambodia (UYFC), one of the CPP-linked youth wings that has swelled to 130,000 members under Many’s watch and is a vital tool for the ruling party to manage the minds of Cambodia’s youth.

The scholar Astrid Norén-Nilsson put it, "Membership provides an opportunity for predominantly middle-class youth to be exposed to the politically influential elite, and is widely expected to improve their professional and other opportunities. The UYFC also engages youth as volunteers at highly visible events which draw broad participation from the general public."

Moreover, Norén-Nilsson noted, Many has also gained power over the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sport (MoEYS), with his UYFC now conducting many of its operations from within the ministry. Since 2013, when Many first became a parliamentarian, he has been chairman of National Assembly’s Commission 7, which oversees the MoEYS.

Also in 2013, Hang Chuon Naron was brought in as education minister, replacing Im Sethy, who, “while a close associate of Hun Sen, was known for his desire to maintain a distance between the ministry and the then Youth Association of Cambodia, the UYFC’s predecessor,” Norén-Nilsson wrote.

Hang Chuon Naron, also a deputy prime minister, was one of the few cabinet ministers to keep his post at last August’s generational reshuffle.

Behind the scenes, Many is likely leading reforms to the education sector. For instance, he is chairman of the organizing committee for Physical Education and Sports teacher selection examination.

More important, though, is civil service reform, one of this government’s top priorities. Appointing Many as minister of civil service, although not ordinarily a prestigious position — the two previous ministers were the fleetingly-remembered Pich Bunthin and Prum Sokha — was a canny move.

It was obvious at the time that the vast bureaucracy, which was already inflated before the last August succession process but has ballooned since, would need to be cut down to size.

It was estimated after the government reshuffle that there were around 1,422 secretaries or undersecretaries of state in the Manet administration, double the number in his father's government. To get the succession process peacefully over the line, thousands of people needed to be appeased with comfy jobs and fat paychecks.

Now, the bureaucracy needs to be trimmed and reformed. Entire ministerial departments will need to be cut and many agencies from different ministries merged. The incompetent and corrupt need to be sacked.

The government vows to instill a new ethos of bureaucrats as servants of the people, not their bosses – or as Many ironically put it, civil service jobs should not be based on "having to know power[ful] people, not having to have a line in ministry, but having exact ability."

Hun Many likely has the political skill to lead this reform and the familial prestige to make sure it’s done as controversy-free as possible. Indeed, these reforms won’t be universally popular. Quite a few people will be left with bloody noses.

So having Hun Sen’s son as the public face for this reform will certainly ease tensions. No one wants to be seen bad-mouthing anything attached to Hun Sen. Making him a deputy prime minister adds even more gravitas.

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. As a journalist, he has covered Southeast Asian politics since 2014. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.