Before U.S. Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin arrived in Cambodia this week, the Pentagon had indicated that the talks wouldn't yield "significant deliverables." Despite some media predictions of a U.S.-Cambodia rapprochement after years of testy ties, Cambodia’s elite politics impose limits to how far relations can recover.

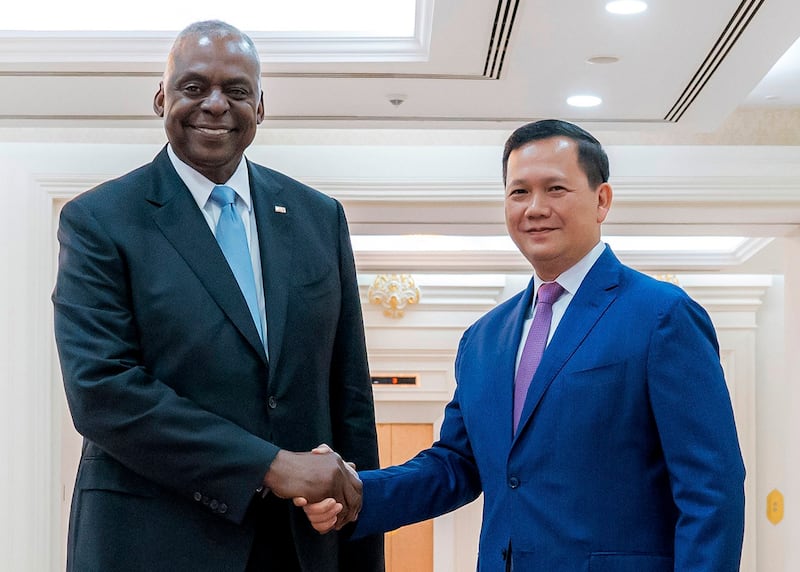

Austin's visit to Phnom Penh came during a trip to Southeast Asia for the annual Shangri-La Dialogue defense summit in Singapore the previous weekend, and Cambodia was one of the few regional countries he had yet to visit.

In July, Cambodia will take over the coordinating role for U.S.-ASEAN Dialogue Relations for the next three years, charged with facilitating talks between the Southeast Asian bloc and Washington. Thus, there are incentives for the U.S. to engage a little more with Phnom Penh.

Ahead of Austin’s arrival, Sun Chanthol, one of Cambodia’s deputy prime ministers, mentioned that Phnom Penh might allow the resumption of "military-to-military" relations in the form of joint exercises on humanitarian and disaster relief. According to a Pentagon readout, Austin discussed the "resumption of military training exchanges on disaster assistance."

However, this is relatively low-level stuff.

In 2017, amid an authoritarian consolidation of power and crushing of the opposition by the ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) that drew U.S. criticism, Phnom Penh canceled the annual joint military drill "Angkor Sentinel" with the U.S., claiming Cambodian troops were needed to manage local elections.

Superficial rapprochement

Since then, Cambodia has conducted military drills with China instead. It is unlikely that Angkor Sentinel will return anytime soon.

Recent U.S.-Cambodia rapprochement has been superficial at best. President Joe Biden voiced appreciation that Cambodia condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, a move orchestrated by then-premier Hun Sen, which cost Cambodia little but gained international favor.

Because Cambodia held the ASEAN chairmanship that year, Western leaders were forced to parley with Phnom Penh – and some presumably liked what they were told.

And in a case of judging someone’s action by their reputation, not the other way around, almost every Western capital leapt onto the narrative that the change of leadership in Cambodia last year – when Hun Sen, the prime minister since 1985, handed over power to his West-Point educated son, Hun Manet – was a convenient moment to change tack.

Indeed, since then, France and Australia have taken the approach long favored by Japan and now won’t say anything bad about Phnom Penh. The European Union got a taste of some environmental policies in Cambodia and now thinks it’s a green partner.

Elusive balance

In Washington, many of the American politicians who were most interested in Cambodia’s domestic politics, as opposed to its role in world politics, have either passed away or left office. Among them, Dana Rohrabacher left in 2019 and Steve Chabot in 2023.

The question now is whether the U.S. can improve relations with Cambodia – which means Cambodia making its relations with the U.S. and China more balanced.

The answer requires a better understanding of why Cambodia aligned with China in the first place.

There are two common explanations. One holds that American interference in domestic affairs, particularly democracy-building, pushed Phnom Penh towards China’s “no strings attached” engagement.

The second is economic necessity: China has provided capital that others could not. By one estimate, China invested around $12 billion between 2011 and 2021, building motorways, ports, railways and other critical infrastructure. Without this money, Cambodia would have struggled to develop such infrastructure or would have had to borrow extensively.

While Chinese investment was a no-brainer for Phnom Penh, losing it wouldn't be catastrophic; the CPP government won't collapse if a Chinese state-run company doesn't build another motorway,

However, both explanations are too simplistic, too focused on conventional governance.

Delicate balancing act

Cambodia remains effectively a feudal system with a complex balance of power among the political nobility and economic barons. The Hun family is at the top, but other elite families have their own power bases, while the tycoons who finance the political system wield considerable influence.

The entire state system is held together by an intricate and delicate balancing act. For all of Hun Sen's strength, he had to plan his son's succession for more than a decade and other political nobles only agreed to it after he doled out thousands of patronage positions and agreed to everyone handing over power to their own children or proteges.

These moves meant that the financial interests and the patronage networks of everyone remained untouched by the reshuffle. There was no consolidation of power by the Hun family.

This has been the system for decades. Since 2010, however, Chinese capital has raised the stakes. Now we're talking about billions, not millions, of dollars flowing at the top of the political system, which has made the dominant clans more powerful yet has made any potential dispute between them far more perilous.

Each clan and network has its own Chinese patron. The clan of Tea Banh, the former defense minister, which controls the defense ministry and some of the southern provinces, including Sihanoukville, is perhaps the closest of the clans to the Chinese military, for instance. Sihanoukville has long been a hotbed for Chinese organized crime.

Thread of Chinese money

The challenge for the U.S. is how to alter a situation where the entire state fabric of Cambodia is intertwined with Chinese money. It's not the case that a few cabinet ministers can sit around a table, decide that maybe Cambodia has become a little too dependent on China and come up with a few balancing policies.

If Prime Minister Hun Manet even considers resetting foreign relations, that would step on the toes of other political nobles and economic barrons. That in turn would upset the intricate balance that stops all of the elites from going after each other.

If a certain powerful family has a vested interest in China having exclusive access to the Ream Naval Base, for instance, does another powerful family risk fratricide by too forcefully opposing this?

Consider also the illegal cyber-scam industry, a major issue for Cambodia and which will likely soon become a new front in U.S.-China tensions. A report by the United States Institute for Peace (USIP) estimates this industry in Cambodia is worth at least $12.5 billion annually, nearly half the country's formal GDP.

Almost certainly some of Cambodia's most important families are connected. After all, you don’t build an industry worth that much without political support, and no self-respecting Cambodian elite would pass up the opportunity of making billions of dollars from it.

The USIP report notes:: “Beijing has found in countries such as Cambodia and Laos that leaders will align closely with China politically in exchange for Beijing ignoring lucrative criminal activity.”

Indeed, it’s a case of the tail wagging the dog. The Chinese government is permitting the industry, which scams Chinese citizens of tens of billions of dollars each year, for geopolitical reasons.

How does America suppose it can wean Cambodia off its dependency with China when a key cause of this situation is not normal government activity, such as investment and trade, but criminality?

How does it convince the powerful in Phnom Penh to end this dependency when Cambodia’s rulers know that doing so would spark major tensions between elites?

David Hutt is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies (CEIAS) and the Southeast Asia Columnist at the Diplomat. He writes the Watching Europe In Southeast Asia newsletter. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of RFA.