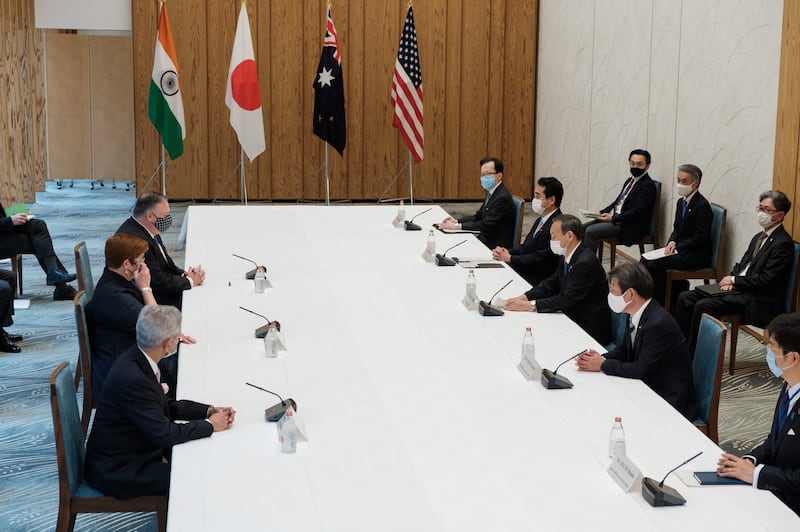

The Economist magazine recently reported that when the United States, Australia, India, and Japan met in 2007 for a quadrilateral dialogue on security matters, many bet that the new grouping would "fizzle."

The magazine noted that once non-aligned India, was “still suspicious of anything that smacked of an alliance.”

But defense ties among the four nations are now rapidly strengthening.

They’d been dormant for a while up until mid-June of this year when a Chinese border patrol attacked Indian soldiers along the lengthy and badly demarcated China-India border in India’s Ladakh region.

At least 20 Indian soldiers and an undisclosed number of Chinese were killed. China refrained from providing any details of its losses.

“This episode helped in no small part to galvanize greater effort among the four QUAD countries to come together, said Collin Koh Swee Lean, a strategic analyst based in Singapore.

“The most telling was India’s invitation to re-join Exercise Malabar after a hiatus since 2007,” Koh said in an email answer to questions from this commentator.

According to Koh, India had been regarded for a while as “the weakest link” within the Quad because of its desire not to provoke China.

Operation Malabar is a trilateral naval exercise involving the United States, Japan, and India as permanent partners. Past non-permanent participants included Singapore and Australia.

Writing for the Financial Times from New Delhi in late October, Amy Kazin notes that India is outgunned by China's navy, which boasts more sailors and weapons, such as submarines, guided-missile destroyers, and aircraft carriers than India.

India’s growing defense ties in Southeast Asia

But retired Indian commodore Uday Bhaskar argues that India still has a significant geographical advantage over China, given its location in the Indian Ocean, through which most of China’s energy supplies have to pass.

Beijing’s strength in this regard is its development of a network of Indian Ocean ports, which are located in Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Djibouti.

These ports concern India because of their potential military use.

India’s growing defense ties in South Asia match a trend that had earlier become evident in Southeast Asia.

Writing recently for the Asia Sentinel website, New Delhi-based editor Neeta Lai reported that in its latest move in that region, India has reached an agreement with the Philippines' government to "strengthen defense engagement and maritime cooperation."

India and the Philippines have been holding Navy drills in the disputed South China Sea along with the United States to reinforce navigation in sea lanes claimed entirely by China.

India has also dispatched coastal surveillance radar systems to the Philippines.

India has offered Vietnam training support for the Southeast Asian nation’s Kilo-class submarines.

And it has offered to train Vietnamese pilots to fly Russian-designed and Indian-built Sukhoi aircraft.

India is providing a U.S. $100 million credit line to Vietnam that allows it to buy defense equipment from India.

On the diplomatic front, Vietnam, for its part, has supported India’s bid to become a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.

A report produced by a senior study group organized by the Washington, D.C.-based United States Institute of Peace (USIP) summed up China’s goals in South Asia and recommended a series of responses.

The bipartisan group included a number of scholars, several U.S. government and congressional experts, and a six-member research team.

China’s ‘grey zone’ provocations

The group concluded that the Ladakh clashes in July of this year put India’s challenge of balancing cooperation and competition with China “in stark relief and will limit China’s ability to pursue opportunities in India for years.”

“China and India are unlikely to make any progress on any final resolution of their border disputes in the near or medium term, the report said.

“Effective protocols for border patrol operations and crisis management can help mitigate tensions but will not stop flare-ups altogether,” it said.

The report concluded that “China’s propensity for ‘gray zone’ provocations and the prominence of territorial issues in both countries’ politics mean a process to delimit and demarcate the border would face huge obstacles.”

Assessing China’s goals, the report’s team said that “Officials in Beijing are driven by aspirations of leadership across their home continent of Asia, feelings of being hemmed in on their eastern flank by U.S. alliances, and their perception that opportunities await across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean.”

“Along their way, the first stop is South Asia,” which the report defines as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

The report says that around the beginning of this century, Beijing’s relations with South Asia began to expand and deepen rapidly.

It says that the ascendance of Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping as China’s top leader in 2012 and the subsequent expansion of China’s activities beyond its borders have accelerated the building of links to South Asia in “new and ambitious ways.”

The report describes South Asia as “a region struggling with violent conflict, nuclear-armed brinkmanship, extensive human development challenges, and potentially crippling exposure to the ravages of climate change.”

But it is also a region “whose economic growth prior to the COVID-19 pandemic was robust, that has a demographic dividend, and whose vibrant independent states are grappling with the challenges of democratic governance—including the world’s largest democracy in India.”

In other words, “China’s expanding presence in the region is already reshaping South Asia, which is simultaneously emerging as an area where U.S.-China and regional competition plays out from the Himalayan heights to the depths of the Indian Ocean.” The report said that “bilateral competition and confrontation make cooperation in South Asia…substantially more difficult.”

Repression limits cooperation

But both nations nominally have a mutual interest in countering violent extremism, ensuring strategic stability and crisis management between India and Pakistan, and promoting regional economic development.”

Yet “bilateral tension and mutual suspicion about each other’s activities in the region restrict the prospects for sustained cooperation beyond rhetoric”

“On crisis management, nonproliferation, and terrorism in particular, differing perceptions about culpability—China mostly taking Pakistan’ side and the United States often agreeing with India—will also make joint efforts difficult to agree on and implement in Afghanistan.”

On crisis management, nonproliferation, and terrorism in particular, differing viewpoints about culpability—China mostly taking Pakistan’s side and the United States often agreeing with India—will also make joint efforts difficult to agree on and implement.

On Afghanistan, the report said, China and the United States have common goals of stopping the spread of international terrorism and reaching a political settlement to bring an end to decades of violent conflict, though how they try to achieve these goals differs in practice.

Further, the report said that Chinese atrocities targeting Uyghurs and other ethnic minority groups in Xinjiang, carried out in the name of countering terrorism, severely restrict possibilities for productive counterterrorism cooperation until Beijing changes its approach to align with global human rights norms.

Meanwhile, China appears have made few official comments on the recent tensions in the South Pacific

But a Chinese specialist on South Asian issues in Shanghai did have comments to make on Operation Malabar, among other things.

Liu Zongyi with the Shanghai Institutes for International Studies said that India’s decision to “dance closely with Washington’s war waltz in the Indo-Pacific was risky.”

His comments were published by the Global Times in Beijing, a tabloid published under the auspices of the Chinese Communist Party's People's Daily newspaper.

Dan Southerland is RFA's founding executive editor.