In what is being described as another case of “debt trap” diplomacy, China’s Export-Import Bank appears poised to take over Uganda’s Entebbe Airport and other assets because the African nation is struggling to service a U.S. $207 million loan for local infrastructure projects.

China – which agreed to expand the airport in 2015 as part of its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) global infrastructure-building program – has denied reports that it may grab control of Uganda's international airport because of the country's failure to pay off the debt.

The site gained infamy in 1976 as the location of the Israeli Defense Force’s daring hostage-rescue operation after Ugandan dictator Idi Amin allowed the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine to land a hijacked Air France jetliner there.

But it is Uganda’s only international airport, which raises questions about China’s domination of critical infrastructure – with very real implications for Southeast Asia.

If it takes place, the debt-for-equity swap in Uganda follows China’s 99-year takeover of Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port and a nearby airfield in 2018, and the 2020 takeover of much of the Lao power grid by a Chinese state-owned firm.

According to a September 2021 report by the AidData project at the College of William and Mary in the United States, Uganda took on 144 Chinese-financed projects between 2000 and 2017, and its sovereign debt to China accounts for 8 percent of its gross domestic product.

But Uganda’s “hidden debt” to China accounted for zero percent of GDP. This is highly unusual.

‘Hidden debt’

Let me explain this in brief terms.

Roughly 70 percent of China’s BRI funding comes in the form of loans, not grants.

Sovereign debt is money that a country’s government owes to foreign and domestic lenders. It is almost never collateralized. But commercial lending from the China Development Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China and other BRI lenders almost always is.

That collateral can take many forms: sometimes China forces the borrower to have a certain amount of assets in a Chinese bank that can be frozen; other times, the recipient country puts up assets as collateral, meaning that it will forfeit those assets if it fails to repay its debt.

Very little of China’s BRI lending is favorable to the borrower. The interest rates average around 4 percent, nearly four times more than World Bank, Asian Development Bank, Japanese, European or American lending.

In addition, in the Philippines, BRI projects have dispute resolution mechanisms that are skewed toward China. This is likely the case in other Southeast Asian BRI agreements.

Another kind of lending – called Other Official Flows, or OOF – involves state-owned companies, state-owned banks, joint ventures, and private sector institutions, rather than central banks. As such, it is not always publicly reported.

The AidData project’s 2021 report found that due to this “hidden debt,” the average government “is under-reporting its actual and potential repayment obligations to China by an amount that is equivalent to 5.8 percent of its GDP.”

Uganda was the 19th largest recipient of Chinese grants and carried very little in the way of OOF loans, and yet it still seems unable to service its debts.

Now of course, China could renegotiate the terms of lending, or write off the debt, as a grant. But Beijing has shown little interest in doing so. Indeed, in March 2021, the Ugandan government sent a delegation to Beijing to renegotiate the loan terms, but returned empty-handed.

Beijing is refusing to budge for two reasons. First, the Chinese are legitimately afraid of creating a precedent. If one country gets to renegotiate the terms, all the others will clamor for the same.

Second, BRI lending really slowed in 2018-2019, which suggests that many of the loans were non-performing. If people aren’t paying back the loans, there’s less for the banks to lend out, unless Beijing injects a lot of new capital. It may be doing that now, as lending seems to be picking up.

How this plays out in Southeast Asia

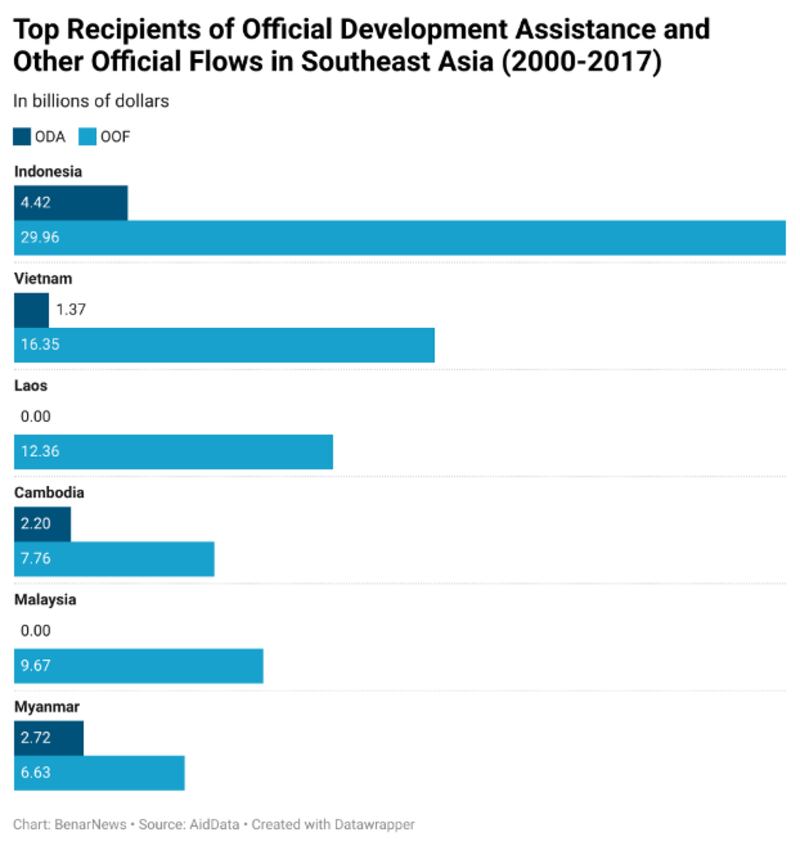

According to the report from the AidData project, China provided $10.7 billion in grants to four Southeast Asian states between 2000 and 2017, and $87.7 billion in OOF loans to six states in the region.

In all countries with the exception of Singapore, which doesn’t borrow from Beijing, sovereign debt loads to China, as a percentage of GDP, range from 1 percent in Cambodia to a whopping 29 percent in Laos. Myanmar is second (5 percent), followed by Vietnam (3 percent). Several states have none. Not including Laos, which is such an outlier, the region’s sovereign debt load to China is a modest 1.4 percent of GDP, on average.

The hidden debt loads tell a different story. The highest amount is Laos at 35 percent of GDP, followed by Brunei (14 percent), Myanmar (7 percent), Vietnam (3 percent), Indonesia (2 percent), and Cambodia (1 percent). Again, excluding the outlier Laos, the average hidden debt to China in the region is 3.4 percent, over twice the amount of sovereign debt.

While 3.4 percent is not unusually high, remember that those loans are at commercial lending rates and are almost all collateralized. Brunei, Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar have public debt exposure to China over 10 percent of GDP. In July 2021, the World Bank estimated that Laos’ overall debt would increase to 68 percent of GDP, up from 59 percent in 2019.

It's hard to imagine that Laos will be able to service its debt for a $6 billion railroad, especially because the Thai government has not completed a rail link that would connect the Chinese city of Kunming to Thai ports – the only economically viable reason for the Lao portion.

Laos has benefited from a recent Thai decision to buy more hydroelectricity, which should allow the Laotians to continue to service debts for their cascade of Chinese-funded dams. Vietnam had to begin servicing a $670 million debt for a Chinese-constructed rail line that still had not opened, after years of delays and a 57 percent cost overrun since the project began in 2011.

With economic slowdowns caused by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, which is unlikely to end any time soon, the region’s hard-hit economies will see weaker recoveries than forecast.

The Asian Development Bank recently downgraded its 2021 growth estimates for every country in the region except for Singapore and the Philippines, and estimated that regional growth would be 3.1 percent in 2021, not 4.4 percent. Revenue will be down for all states, while the continued public health and stimulus costs are rising.

All of this will impact the ability of regional states to service their debt.

China may be willing to play harder ball with African countries than with neighboring Southeast Asia, where public perceptions about China are starting to sour. But China keeps pushing its BRI projects on the region, with new projects announced in Malaysia, and a determination to see projects completed in Myanmar despite the civil unrest since the Feb. 1 coup d’etat and an 18 percent contraction of the Burmese GDP.

The region’s high levels of public indebtedness – and fear of asset seizures by China – should raise a lot of concern, both among Southeast Asian governments and their citizens. And BRI’s heavy reliance on Chinese workers and managers who tend not to return home, shoddy construction, environmental degradation, and corruption should raise even more concern.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or BenarNews.