Eight months after a major water pollution disaster in China's Songhua River, Russian officials are still complaining about the damage caused in the downstream regions and calling for a Chinese cleanup.

The chemical spill from a factory explosion near the Songhua River in the northeastern province of Jilin last November continues to trouble residents on the Russian side of the border.

Officials in the Far East region of Khabarovsk have banned swimming and fishing in the Amur River, known as the Songhua River upstream in China.

After meeting with Heilongjiang governor Zhang Zuoji on July 3, Khabarovsk governor Viktor Ishayev issued a statement demanding that China take responsibility for cleaning up the Amur.

The concentration of E. coli bacteria in the river is twice the normal level, while the toxin phenol is seven times over the standard and heavy metals are four times higher than usual, the Russian governor said.

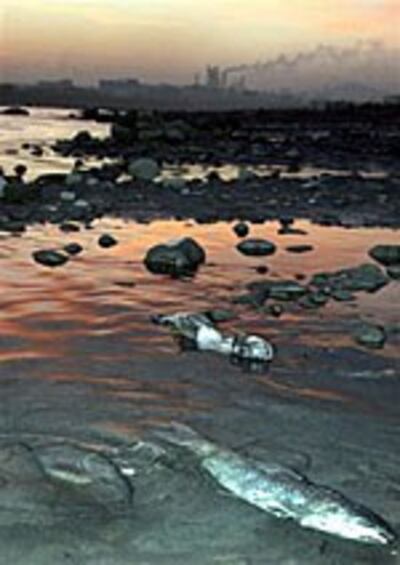

Heavy pollution in Songhua

Jennifer Turner—coordinator of the China Environment Forum at the Washington-based Woodrow Wilson Center and co-author of the recent book Reaching Across the Water—said that last year's spill was only part of the problem.

I think it’s admirable that the governor in the Russian Far East is speaking out.

Turner told RFA's Wu dialect service that pollution had been going into the Songhua “from all the factories in Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces.”

Ishayev’s decision to speak out appears to represent straight talk from a regional official about environmental damage, Turner said.

“I think it’s admirable that the governor in the Russian Far East is speaking out.”

David Gordon, executive director of the San Francisco-based non-governmental organization Pacific Environment, said he has heard concerns about China’s chemical dumping voiced by scientists, officials, and fishermen in the Russian Far East for the last 15 years.

Gordon noted that safety questions about drinking water and eating fish from the Amur river had yet to be fully answered.

Reporting constraints

“We believe in the precautionary principle, which is, do not assume that it’s safe until it’s been tested and proven to be safe. Our knowledge of the Amur is that it’s not yet safe.”

Gordon’s group follows reports on the Songhua and other pollution issues in the region on its Web site, www.pacificenvironment.org.

But reporting on China’s environmental problems could become tougher as the result of a proposed new Chinese press law.

The measure would require both domestic and foreign news organizations to seek state approval before reporting disasters and accidents, China’s official news agency Xinhua reported in June.

Journalists could be fined up to 100,000 yuan (U.S.$12,500) for reporting accidents such as the Songhua spill if they are not authorized to do so.

David Gordon said the law could have serious consequences for safety and the environment, noting that officials first tried to dismiss the Jilin accident as a rumor.

“Only through the efforts of local journalists did, in fact, the truth come to light so that people could know in Harbin and further down the river that their water was polluted and that they needed to be very, very careful and not ingest that water.”

Restrictions on the press could conflict with government pledges to keep the public informed, Gordon said.

Original reporting by Michael Lelyveld. Edited for the Web by Richard Finney and Luisetta Mudie.