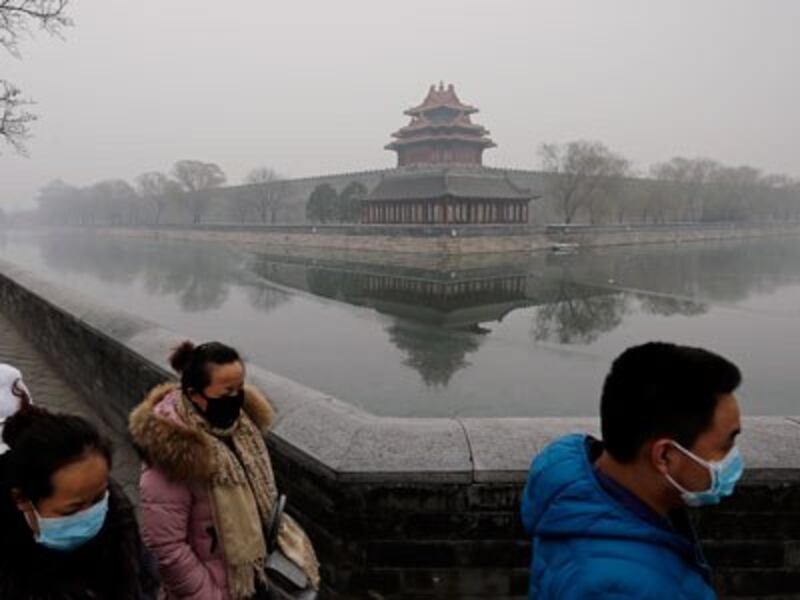

China is gradually transforming its economy and patterns of energy consumption, but it may be decades before citizens see dramatic improvements in air quality, according to a recent report.

The finding this month by the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) came as an international group of climate scientists blamed an increase in China's coal consumption for the first big rise in global greenhouse gas emissions since 2013.

The warning from the Global Carbon Project of a two-percent jump in 2017 emissions coincided with the IEA's release of its long-range energy forecast and its first in-depth China analysis in the past 10 years.

In its 2017 Global Carbon Budget, the scientists' group cited a projected three-percent rise in China's coal use this year and a 3.5-percent increase in emissions as causes of the climate setback after three years of relative stability.

"The 2017 growth may result from economic stimulus from the Chinese government, and may not continue in the years ahead," the scientists said during the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Bonn, Germany.

Speaking at the conference, China's top climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua acknowledged the findings but argued that the higher emissions were not the start of a trend.

"Carbon emissions do fluctuate, but a single indicator cannot reflect the whole picture," Xie said in remarks reported by the official English-language China Daily.

The IEA's long-term analysis as part of its annual World Energy Outlook was generally positive about the decarbonization trends of China's transition to more sustainable economic growth and cleaner fuels.

Even so, some details of the 780-page study may raise concerns about how long it will take for China's "war on pollution" to pay off with public health benefits in terms of exposure to fine particulates known as PM2.5, mainly from coal.

As it stands now, only about two percent of China's nearly 1.4 billion people breathe air that meets World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, the IEA said.

That proportion would rise to only three percent by 2040, even if China meets all the targets set in its expected economic, energy and environmental plans, according to the report.

The massive IEA study does not present an overarching theme, as the agency's annual forecast did five years ago in predicting a "golden age of gas."

Instead, it is a collection of hundreds, perhaps thousands, of implications of energy data points and emerging trends with consequences for the global economy and the environment.

Changes in the global scheme

Sweeping shifts are predicted as a result of factors including greater U.S. oil and gas production, lower costs for renewable energy, broader use of electricity and China's economic transition, the IEA said.

China's place in the global scheme has changed since the last major analysis. Projections of its energy use and emissions are falling behind those of India and Southeast Asia in long-term forecasts of world growth.

But it continues as the leading emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2), with 28 percent of the world total in 2016, making its carbon reduction efforts critical to both climate change and smog.

Echoing earlier studies, the IEA estimates that outdoor air pollution causes nearly 1 million premature deaths in China annually, while indoor pollution claims an additional 900,000 lives.

China is already ranked first in growth of renewable energy, but high-polluting coal still accounts for nearly two-thirds of primary energy use, the IEA said.

With contributions from solar, wind and nuclear sources, low-carbon generation capacity will surpass that of fossil fuels in power production by around 2025 under the study's "new policies scenario," which includes agreed and intended plans.

China's transition to a slower-growing economy, driven by services, consumption and light industry rather than investment and heavy industry, promises continued gains in energy efficiency and lower rates of demand.

The share of all fossil fuels in primary energy demand will slowly slide from 89 percent in 2016 to 76 percent in 2040. Demand for coal is forecast to decline at an average annual rate of 0.6 percent.

But other trends in China's complex transition may limit the relief that citizens can expect. Demographic shifts are a major factor.

Urbanization is proceeding at a rapid rate, exposing a higher proportion of the population to pollution, while the average age is also rising.

The phase-out of firewood and biomass for cooking in rural areas may reduce indoor deaths to 500,000 by 2040, but premature deaths from outdoor pollution could rise to 1.4 million with the more elderly population, even though PM2.5 may fall to half of current levels by then.

By the end of the forecast period, the share of the population older than 65 will grow to 14 percent from 4 percent now, the study said.

The presence of uncertainties

To a greater degree than previous annual outlooks, the study frequently cites uncertainties in its forecasts.

"There is no certainty about the CO2 emissions outlook for China," the study said. "It is entirely possible that emissions could peak later than 2028, or indeed earlier. But perhaps the bigger issue is uncertainty about the actual level of the peak."

One major concern is the pace of China's economic transition.

A 10-year delay in the reform agenda could add more than 1 billion metric tons to coal demand, or 35 percent, to the central projections for 2040, the IEA warned.

Although the study does not say so, China's credit-fueled growth spurt to spur recovery this year from a slump in 2015 has raised questions about its commitment to sustainable growth policies.

In the first three quarters of this year, China's gross domestic product topped government targets with a growth rate of 6.9 percent, rising from a 6.7-percent pace in 2016.

Infrastructure spending has driven demand for building materials including steel, despite the government's directive to cut production overcapacity in the industry.

The study estimates that lower iron and steel output accounts for about 80 percent of the projected decline in coal consumption by 2040.

Failure to meet the capacity cutting targets for steel and cement could add 100 million tons of coal equivalent to the energy total in 2040, nearly equal to South Africa's current coal consumption now.

A 10-year delay in meeting targets for lower steel and cement output would increase CO2 emissions by 5 gigatons, or more than all the current emissions from China's power sector.

China's own official statistics this year have not been encouraging.

In the first 10 months of the year, steel production climbed 6.1 percent from the year-earlier period after rising 1.2 percent in 2016, according to National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data.

Pig iron production is up 2.7 percent, and coal output has risen 4.8 percent, the NBS said.

Renewed outbreaks of winter smog in China's northern cities may also be a sign of unreported coal burning despite the government's push to require heating with natural gas.

At a pre-release press conference for the IEA report, the study's main authors were asked about concerns that China's higher rates of GDP growth and steel production this year may conflict with forecasts.

"It shouldn't be taken for granted that China jumps into this new era with no bounds whatsoever," said Laura Cozzi, head of the IEA's energy demand outlook division, in response to questions from RFA.

Cozzi said the agency had analyzed the consequences of delay or failure to meet China's targets for transition to more sustainable growth.

"I think the findings are quite remarkable and quite important, and we are telling those to Chinese policy makers, as well," Cozzi said.

Tim Gould, head of the supply outlook division, said the IEA was "aware of the data coming in, in relation to China's coal consumption" so far this year.

"I think it's too early to draw definitive conclusions from that," he said.

"Our analysis is really trying to look at longer-term structural trends, even while we pay very close attention to the short-term data," he said.