After years of friction over currency policy, China's inflation may become a new concern for the United States.

On Feb. 4, the Treasury Department issued a long-awaited report to Congress on China's monetary practices but declined to cite it for currency manipulation as critics have urged.

U.S. manufacturers have argued for years that China deliberately undervalues the yuan by as much as 40 percent to give its exports an unfair price advantage, causing the loss of American jobs.

But in its report, Treasury said the yuan is actually climbing faster than it seems because of China's growing inflation.

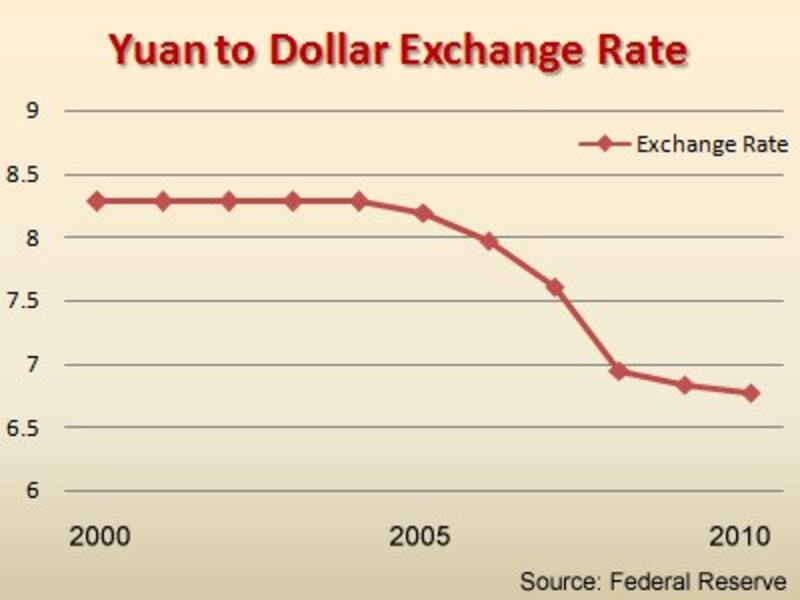

Going strictly by "nominal" exchange rates, the yuan has risen 3.7 percent against the dollar since last June, or 6 percent on a yearly basis.

But with China's greater inflation factored in, the yuan is strengthening at a 10-percent rate in "real" terms, said the Treasury report while noting that the currency remains "substantially undervalued."

U.S. officials appear to have heeded the advice of economists like Harvard's Dale Jorgenson, who told Radio Free Asia in November that Washington has been "too focused" on the yuan's nominal rate.

"It's the real exchange rate that matters," Jorgenson said.

Significant difference

Treasury estimates that inflation was 5 percentage points higher in China than in the United States in the second half of last year, making a significant difference in real terms.

If Treasury and the economists are right, China's inflation could erase more of the undervaluation in coming months.

The government has already raised its inflation target to 4 percent for 2011 after topping its 3-percent limit last year. Officially, China's consumer price index (CPI) reached

3.3 percent but economists believe it was grossly understated.

"Inflation may be substantially higher than the government is letting on," said Gary Hufbauer, senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington.

Some estimates put actual CPI growth at 10 percent or more. That figure could rise even higher this year due to drought in farming regions of China, which may drive up food costs.

According to the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), China's CPI reached a year-on-year rate of 5.1 in November before easing to 4.6 percent in December. Last year, CPI in the United States was just 1.5 percent.

U.S. legislation

But critics aren't buying the inflation argument.

"It's as plain as the nose on your face that China manipulates its currency," said Democratic Senator Charles Schumer of New York, who has backed legislation that could lead to tariffs on imports from China.

"It's just as plain that the only way to address this problem is for Congress to act," Schumer said.

Last week, Senators Sherrod Brown, Democrat of Ohio, and Olympia Snowe, a Maine Republican, introduced legislation that would direct the Commerce Department to "treat currency undervaluation as a prohibited export subsidy."

Hufbauer said Congress is more likely to look at numbers like the U.S. trade deficit with China in considering whether to pass currency measures this year.

In 2010, the trade deficit with China soared over 20 percent to a record $273.1 billion, the Commerce Department reported last week.

Alan Tonelson, research fellow at the U.S. Business and Industry Council in Washington, argued that currency policy should not be based on China's "unreliable" CPI figures.

"It's only the latest smokescreen," said Tonelson. "We're focused on getting Washington to move against a long-standing problem."

Export dependent

Tonelson rejected Treasury's argument that inflation is eating away at the exchange rate gap as a suggestion that "the problem will take care of itself."

"We dismiss that as cynical and self-serving nonsense," he said.

Tonelson argued that China's economy is even more export dependent than it was eight years ago when U.S. industry began its campaign against the exchange rate policy.

The reason is that China's consumer market is not yet developed enough to keep its huge labor force employed. The result is that the government shifts from one export-driven tactic to another, regardless of short-term exchange rate trends, said Tonelson.

While Treasury sees some positive movement on closing the currency gap as a result of inflation, both economists and critics are on guard in case Beijing tries to turn the argument around.

If its prices keep rising this year, China may be able to make the case that it no longer needs to let the yuan appreciate in nominal terms because inflation is doing the job.

Chinese argument

Hufbauer said he has already started to hear the argument from Chinese economists.

"In my meetings, they've already begun to talk about it, and I think it will feature more heavily," he said.

On Sunday, Yi Gang, vice-governor of the People Bank of China (PBOC), argued that the exchange rate is now at "an appropriate level," the official Xinhua news agency reported, citing the Treasury's estimate that the yuan had risen 10-percent in inflation-adjusted terms.

"So far, the International Monetary Fund at least is not buying that argument as a reason to back off from urging China to appreciate," said Hufbauer.

"The Chinese will use that argument but I don't think it will sway the rhetoric to a completely hands-off attitude, which China would love to see," he said.

Tonelson was asked whether his group would accept rising inflation as a valid reason for slowing appreciation.

"Absolutely not," he said.

Treasury has been trying to make the opposite case to China, arguing that appreciation will help to control inflation by reducing pressure to convert dollars into yuan.