China is strengthening its strategic ties through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), but experts say there is little chance it will benefit from a proposed SCO “energy club.”

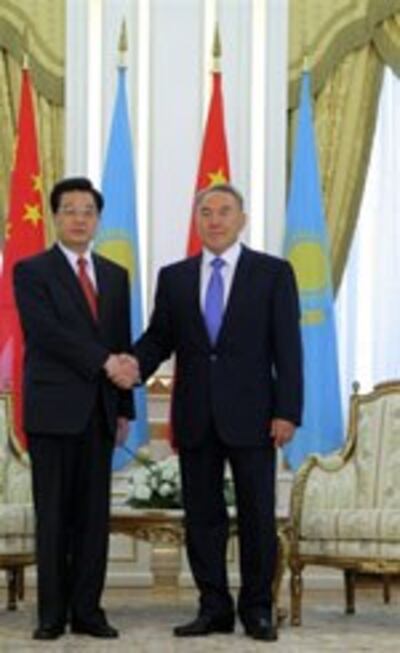

On August 16, China’s president Hu Jintao joined the leaders of Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan for an annual SCO summit in the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek, marking increased coordination within the six-year-old security group.

The summit was accompanied by extensive joint military exercises, with some 6,000 troops from SCO member states taking part with combat aircraft, artillery, and armored vehicles.

Plans to create an SCO energy club to serve the common interests of the group’s members may prove to be unworkable, though, analysts say. Cooperation on energy, including comparisons of national energy strategies, may be difficult because member states compete.

A zero-sum game

In an interview with Radio Free Asia, Martha Brill Olcott—a Central Asia expert and senior associate at the Washington-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace—said that “in some areas, energy in Central Asia really is a zero-sum game.”

“You can’t ship the same gas in two directions at once,” Olcott said.

China and Russia, for example, compete for non-SCO-member Turkmenistan’s rich gas resources, Olcott said. While Russia wants all Turkmen gas to flow through Russian territory, China would provide both an alternate market and a pipeline route that could benefit Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan.

“So I can see where China feels that it has a lot to offer the Central Asian states in terms of strengthening their negotiation position with Russia … but I don’t see where Russia gains a whole lot from sitting at the table as an equal with these five other states.”

Russia has been trying to reach an agreement for its own gas sales to China, but talks have stalled for two years because China refuses to meet Russia’s price demands. In addition, Olcott said, Russia and China operate differently in pursuing their energy interests in the region.

“Russia in general has preferred to use a bilateral approach in securing its long-term energy supplies, and its long-term gas supplies in particular, whereas China is effectively forced to have a multilateral approach because you have to cross more than one country to get gas from Central Asia to China, with the exception of Kazakh gas.”

Mutual suspicions

Mikkal Herberg, research director of the energy program at the Seattle-based National Bureau for Asian Research, said that Central Asian nations must cooperate on pipeline transit to get their resources to export markets in the east.

An SCO role in this “would seem like a logical thing,” Herberg said.

“But when you look at the on-the-ground facts of how suspicious each one is of the others … it’s difficult for me to see that the SCO’s really going to change that,” he said.

Asked whether SCO nations might be willing to share sensitive commercial information, Herberg said “Nobody’s going to divulge what their pricing concerns are and what prices they’re willing to pay.”

“These are all very tough strategic issues for each of the countries. It’s difficult for me to imagine that they’re going to hand any real significant authority over to a Central Asian authority or SCO authority for that.”

Original reporting by Michael Lelyveld. Edited for the Web by Richard Finney.