After Beijing imposed the draconian National Security Law for Hong Kong in 2020, the UK, Canada and Australia responded by opening "lifeboat schemes," or special immigration pathways, for Hong Kongers. Article 23, the latest tightening of the screws on Hong Kong freedoms, requires a similar response from the European Union.

The UK provided an escape valve by allowing Hong Kongers with British National (Overseas) (BNO) status to apply for a visa with a permanent residence pathway in Britain. More than 160,000 Hong Kongers have resettled in the UK alone since the imposition of the law, and London has taken further steps to welcome them in anticipation of the passage of Article 23..

Canada launched programs to provide permanent residency to Hong Kong residents who have graduated from a selected post-secondary institutions in Canada, and to Hong Kongers who have completed post-secondary education and have worked in Canada for a minimum of one year.

Australia enabled Hong Kongers completing eligible tertiary studies to apply for a temporary graduate visa after their studies, with a pathway to permanent residency.

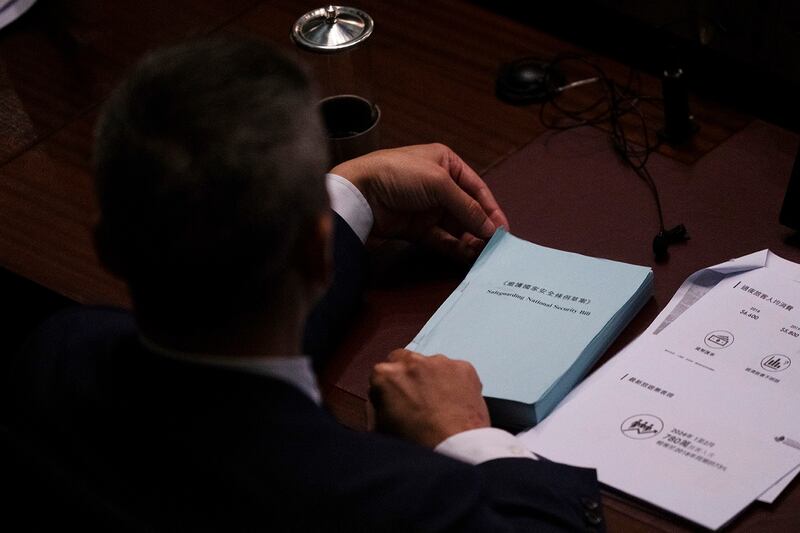

This week, the Hong Kong government enacted the Safeguarding National Security Bill, colloquially known as "Article 23 legislation," in the territory. Article 23 is a domestic, albeit more severe, version of the National Security Law, and was first proposed in 2003.

Under the Basic Law of Hong Kong, the city’s constitution, the Hong Kong government is required to introduce legislation to safeguard national security. In recent days Hong Kong officials have said that it is their constitutional “duty” to introduce Article 23 legislation, but I am not sure that broad and unclear language is what the writers of the Basic Law had in mind.

When the Hong Kong authorities attempted to introduce Article 23 in 2003, more than 500,000 Hong Kongers protested, and the plans were abandoned. But today, the Hong Kong people do not have a choice nor the right to protest without facing serious repercussions.

Vague terms

Under directives from Beijing to pass Article 23 "as soon as possible," the Hong Kong government left a few days to consider a public consultation process which received over 13,000 submissions and for the Hong Kong Legislative Council to review and make amendments to the 212-page bill.

Article 23 prohibits seven types of activities: treason, secession, sedition, subversion, theft of state secrets, foreign political organizations or bodies conducting political activities in Hong Kong, and political organizations or bodies in Hong Kong establishing ties with foreign political organizations or bodies.

The language surrounding what constitutes these activities is vague to intentionally allow the government to criminalize whatsoever and whosoever it wishes. For example, starting with the definition of ‘national security’, the bill reads “specific measures to be taken to safeguard national security will depend on the actual situation in the HKSAR.”

Under which circumstances, and in what situations, will certain individuals and organizations be criminalized? This language not only mirrors the definition of national security on mainland China, but potentially contravenes the “principle of legal certainty” protected under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Article 23 also poses a major risk to Hong Kongers in exile abroad, particularly the 13 in the UK, U.S. and Australia who continue to be targeted by the Hong Kong authorities with arrest warrants with HK$1 million (US$127,800) bounties. The legislation refers to such individuals and others who have fled from Hong Kong to seek refuge from repression as “absconders,” and includes provisions which allow the Hong Kong government to cancel their Hong Kong passports.

Hong Kongers in the EU are not immune. In December 2017, the Hong Kong government issued an arrest warrant for Ray Wong, the first Hong Konger to secure asylum in Germany. The prosecution in the show trial of British citizen Jimmy Lai has also cited Wong’s name.

Under Article 23, the likelihood and severity of arrest warrants with bounties and transnational repression, as well as the targeting of exiled Hong Kongers’ family members and friends who remain in the city, will only increase.

Deterioration of rights and freedoms

After the imposition of the National Security Law, Hong Kongers hopped on planes to welcoming countries, used speedboats to flee to Taiwan, or accepted jail terms.

In response to the enactment of Article 23, EU member states should link arms with allied nations to introduce lifeboat schemes for Hong Kongers. This would not only provide thousands of Hong Kongers with needed safe haven, but send a strong message to Hong Kong and Chinese officials that crackdowns on basic civil and political liberties will not be tolerated.

The first step is for EU member states to introduce pilot lifeboat schemes, which, for example, would allow up to 100 Hong Kongers each year to apply for five-year work visas in areas where there are shortages of skilled labor. Opening lifeboat schemes for Hong Kongers would be consistent with previous recommendations from the European Council and European Parliament calling for a review of immigration schemes for Hong Kongers in the EU.

The National Security Law of 2020 was Beijing warning Hong Kong officials to remember who runs the show. Now, the passage of Article 23 is confirmation of the tightening relationship between Beijing and Hong Kong officials, as well as the utter deterioration of rights and freedoms in the once-thriving international financial hub.

Hong Kongers have a track record of participating in civil society and peacefully defending democratic values, and in every country they relocate to, they contribute to local communities, the economy, the workplace and education, including in high-skilled jobs. They would contribute to the greater EU and national economies as they have in the UK and elsewhere

With Russia’s war on Ukraine, the crisis in Israel, and threats to Taiwan looming on the horizon, the EU must not let this further assault on Hong Kong’s already diminished freedoms, rights and the rule of law go unchallenged and it should not miss this important opportunity to provide a lifeline to Hong Kongers in their darkest hour.

Megan Khoo is a research and policy advisor at the international NGO Hong Kong Watch. Khoo, based in London, has served in communications roles at foreign policy non-profit organizations in London and Washington, D.C.. The views expressed here do not reflect the position of Radio Free Asia.