The first anniversary of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine has largely gone unnoticed in Southeast Asia, despite the war’s economic impact, the potential loss of a key arms supplier, and the dangerous legal precedent that was set.

Southeast Asian governments have been self-interested, more concerned about securing wheat and cheap oil than they have been about standing up for international law and supporting a country that’s fighting in self-defense.

The messaging

Ukraine’s messaging and the strategic communications of President Volodymyr Zelenskyy have made a deep impact in the West. This has not been the case in Southeast Asia.

In part, this is because prior to the invasion, Russian President Vladimir Putin enjoyed high favorability in Southeast Asia. He was seen as a strong leader who presented a non-Chinese alternative to the United States, and a champion of a multi-polar world, who had no territorial ambitions in the region.

The Russian narrative is pushed out through propaganda platforms and is amplified by Chinese state media that provide free Xinhua and CGTN feeds to regional print and TV media.

In some countries, such as Vietnam, Ukrainian messaging has been censored or impeded. The state media in Vietnam, not to mention their army of red bull influencers and trolls, has been very pro-Russia despite Moscow's battlefield losses in Ukraine.

Moscow’s media and influence operations have effectively shifted the blame to the United States, alleging that NATO expansion justified Russian self-defense. Too many people in Southeast Asia are too eager to blame the United States for international conflicts.

While there is some sympathy for Ukraine, because of Moscow’s success in spreading its propaganda in the global south, there’s been too much “both sides-ism.”

Official policies

Other than Singapore or Cambodia, no countries in Southeast Asia have strongly defended the principles of international law, spoken out against the illegality of changing borders by force, or have shown a willingness to explicitly condemn Russia.

Indonesia’s policies have evolved the most significantly over the past year.

The “military attack on Ukraine is unacceptable,” Jakarta said without naming Russia as it called for de-escalation.

As chairman of the G20, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo pushed through a joint declaration condemning Russia’s invasion, and Indonesia’s language has been stronger since.

Former Malaysian Foreign Minister Saifuddin Abdullah summed up Putrajaya's position: "Malaysia does not support either side of the conflict." It offered to evade sanctions and sell semi-conductors, before threats of western retaliation. Even the new government of Anwar Ibrahim has maintained a stance of unprincipled neutrality.

Thai Prime Minister Prayuth Chan-o-cha pandered to Putin in the hope that he would attend the APEC summit; which he still failed to do. Some 200,000 Russians have fled to Thailand where they are avoiding conscription and the economic downturn.

Singapore has remained the most steadfast in its condemnation and the only country in the region that sanctioned Russian financial institutions. It’s also helped enforce U.S. Treasury Department designations on three firms that were evading sanctions.

The Philippines has taken an increasingly more principled stance and President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. has publicly supported President Zelenskyy and defended Ukraine’s right to self-defense.

Vietnam’s ambassador to the United Nations made a principled defense of international law and the U.N. Charter, criticizing the altering of borders by force. Yet Vietnam’s long history with Russia has shaped its actions.

Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stopped in Hanoi and held high-level meetings with his counterpart and Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh last July and participated in Russia's Army Games. Yet no country in the region is more vulnerable to the dangerous legal precedent that Moscow used to justify its invasion, which China endorsed.

Myanmar's military government is the only government in the region that said Russia's invasion of Ukraine was "justified." Coup leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing met with Putin in Vladivostok in September and secured subsidized oil and discussed arms sales. Two Myanmar banks opened offices in Moscow in an attempt to evade sanctions on both countries and avoid dollar-denominated trade.

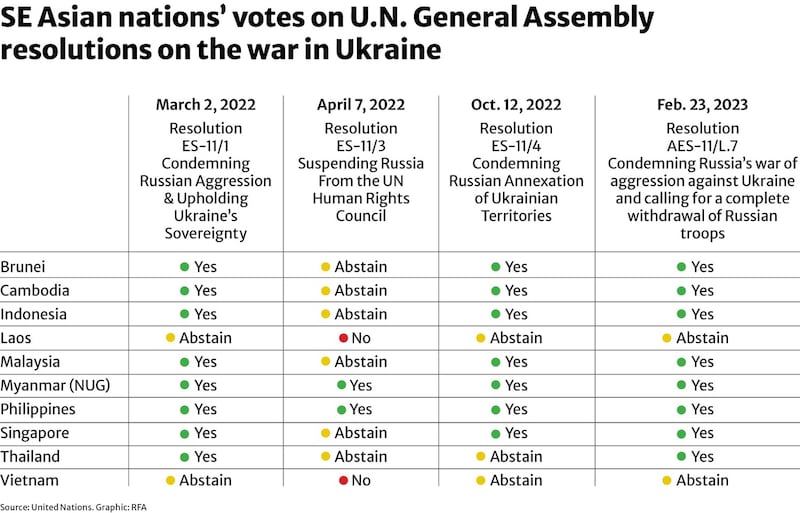

Russia’s two closest allies are Vietnam and Laos, both of whom, in U.N. General Assembly resolutions, abstained in condemning the Russian invasion, the condemnation of Russian annexation of provinces in eastern Ukraine and in the call for a complete withdrawal of Russian troops.

The most steadfast supporters of Ukraine have been the Philippines and Myanmar, whose seat in the United Nations is under the control of the opposition National Unity Government. All the other countries, including Thailand, have split their votes, condemning the invasion, annexation, and calling for a withdrawal, but abstaining in the vote to expel Russia from the Human Rights Council.

Inflationary pressures

The war has had a direct impact on commodity prices in Southeast Asia. Wheat, which was already at record high prices, went up by 30% due to the invasion, as fighting centered in the Ukrainian wheat belt and Russia bombed or blockaded ports. Ukrainian grain exports fell by 29% in 2023.

This in particular impacted Indonesia, Vietnam, and the Philippines. But regional elites went out of their way to blame anyone but Russia. And wheat prices, though down from their summer 2022 high, are still where they were at the start of the war last February.

This was unwelcome news from governments who now had inflation on top of slow growth as they emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic. Inflation in the region has been at a low of 5% in Vietnam and up to nearly 40% for Laos and Myanmar.

While Indonesia tried to present itself as a peacemaker with President Widodo’s mid-2022 visit to Moscow and Kyiv, his priority was assuring the export of wheat and securing cheap Russian oil. To put it into perspective, Urals crude oil today is trading 31% lower than the benchmark Brent crude oil.

Russian arms

Between 2010-2019 Russia sold nearly U.S. $11 billion in arms to Southeast Asia.

Countries that rely on Russia for arms, in particular Vietnam and Myanmar, should be re-evaluating their procurements. Russia has no ability to produce for export markets given the rate at which its forces in Ukraine are burning through equipment and ammunition.

International sanctions on everything from semi-conductors, replacement parts for machine tools, to ball bearings, have ground production down to a halt. Moreover, Russian arms have not proven themselves to be of good quality and perform well.

Myanmar took delivery of two of six SU-30s that it purchased; It’s not clear when they will receive the remaining four.

Vietnam, had already been seeking to diversify its supply chains, largely benefitting Israel and India. Hanoi feted 119 defense contractors from 28 countries at their defense expo in December 2022. If anything, Vietnam is poised to offer spare parts, missiles and munitions to Russia.

Indonesia has over-diversified its arms suppliers. While it has imported SU-27 and SU-30 fighter-jets, Mi-35P and Mi-17 helicopters, armored personnel vehicles, artillery, and anti-ship missiles from Russia, it’s a small market for Moscow, and thus won’t be a priority.

Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam, which all fly SU-27s, have to consider that spare parts are going to be very hard to come by in the coming years, and some of their wings will be grounded.

In March 2022, the Philippines scrapped its only major defense deal with Russia, a $227 million helicopter deal for six Mi-17 helicopters, to avoid CAATSA Sanctions from the United States. The Philippines is trying to get its down payment back, which seems highly unlikely at this juncture.

In sum, the governments of Southeast Asia will continue to have fairly weak responses to a distant conflict; ignoring the economic costs imposed, shifting blame elsewhere. Inexplicably for small and medium-sized states that rely on the principles of international law, they remain too craven to defend the U.N. Charter.

Their stances will remain parochial, not principled. Most see little reason in provoking Russia, despite overall limited economic engagement with the region, and are aware of Beijing’s “no-limits” friendship with Moscow.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or RFA.