Vaclav Havel’s death at the end of last year took me back to my travels as a student to Eastern Europe during the Cold War.

As an exchange student in West Germany in the late 1950s, I had an opportunity to visit Moscow, East Berlin, several Polish cities, and finally Prague, the Czech capital.

I felt that Prague had the most controlled and repressed atmosphere of any of those East Bloc cities.

It was impossible for me to imagine that a dissident such as Havel would emerge in a country like Czechoslovakia.

An opening in Poland

And it was even more unthinkable that this tightly controlled country would later undergo a “Velvet Revolution” under the leadership of Havel and a small number of other brave souls. In the end, Havel became president of the country.

If I’d been older, wiser, and more experienced, I might have recognized the significance of a few small signs of dissent during an evening spent with a Czech engineer who took me into his home one evening in mid-August 1957.

I had come to Prague from Poland, where I had spent a glorious week. Poland was opening up to new ideas thanks to a wave of de-Stalinization and reforms introduced by Wladyslaw Gomulka, the Polish Communist Party leader. People on trains and in the streets were talking about “freedom.”

Meeting a ‘real communist’

While in Warsaw, I had a mini-debate with an East German Communist Party official who was escorting a group of East German students on a trip to Poland. I told the students that I wanted to meet a real communist, and they introduced me to him.

Although the official defended communism and derided my belief in God, he admitted that most East Germans were unhappy with their government!

But Prague was something else.

I immediately encountered a kind of bureaucratic communism that I hadn’t seen in Poland. I spent an entire afternoon trying to change a $10 bill. The first bank I went to wouldn’t accept the bill because a tiny corner was torn off.

I tried another bank, but they sent me back to the first bank. I then tried to change a German 50 mark bill, but the bank had no change for it. Just before closing, they sent me to a third bank. That bank changed the German bill, but not before three clerks had scrutinized it.

In the streets of Prague, people were much more reluctant to talk than were the Poles or even the East Germans whom I had met.

A chance encounter

But then my luck changed. I got lost and started asking for directions. A passerby named Zdenek Teply said that he would show me around Prague that evening, and he did.

He also invited me to his home for dinner.

Teply was an engineer who lived with his wife and mother-in-law in a small apartment. He didn’t have enough food on hand for a full-scale dinner so he served jelly-filled rolls and tea with rum.

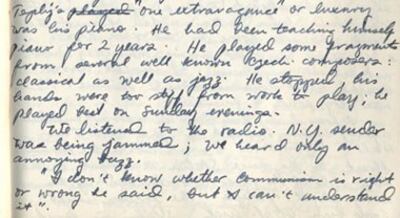

Teply declared that his “one extravagance” was his piano, and he played some jazz as well as passages from Czech composers.

Then he tried to tune in an international radio broadcast, but it was jammed. All we could hear was a buzzing sound.

A sign of dissent

Teply seemed to enjoy the conversation he was having with the first American he had ever met. He suggested that I stay overnight at his apartment but then quickly decided that the Palace Hotel, where I had reserved a room, might notice that I was absent that night and conclude that something suspicious was going on.

Aside from our failed attempt to hear an international broadcast, nothing seemed all that unusual that evening until—out of the blue—Teply made a comment about communism that was the only real sign of dissent that I had detected during two days in Prague.

“I don’t know whether communism is right or wrong,” he said, “but I can’t understand it.”

I know that these were his exact words, because I noted them in my diary at the time, a diary that I managed to find on a shelf in my study following Havel’s death.

I didn’t realize that Teply’s comment probably reflected a degree of unrest that lay under the surface of Prague’s repressive atmosphere.

Looking back

Looking back on my conversation with Teply more than half a century later, I can’t help but think that there might be many more Teplys in countries that now appear frozen by fear. Even North Korea comes to mind, where an ill-advised remark can send you to the gulag.

Twenty years after I met Teply, Vaclav Havel and 241 other dissidents produced their Charter 77, issued in early January 1977. Charter 77 criticized the Czech government for failing to honor human rights pledges contained in the Czech constitution.

I was a diplomatic correspondent at the time, working for The Christian Science Monitor out of Washington, D.C. I recalled the frozen atmosphere of Prague and thought that Havel and his relatively small band of dissidents must be crazy. How could these advocates of nonviolent resistance ever succeed?

But within weeks after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, Czechoslovakia’s communist leaders stepped down in a peaceful transfer of power. Havel was later to become the first president of a post-communist Czechoslovakia.

A democratic East Asia?

There is a tendency today to dismiss the Cold War as holding no lessons for today’s rapidly changing world. But when some experts assert that China, Vietnam, or North Korea are unlikely to become democratic for many years to come, I hark back to that time in Prague when it was impossible for most of us to predict the Velvet Revolution.

Despite recent crackdowns on dissent in China and Vietnam, one expert on the prospects for democracy, Larry Diamond, takes a contrarian view in the current issue of the Journal of Democracy. He concludes that “if there is going to be a big new lift to global democratic prospects in this decade, the region from which it will emanate is most likely to be East Asia.”

He draws this conclusion partly because East Asia, unlike the Arab world, in his view already has “a critical mass” of democracies.

Within a generation or so, he predicts, “it is reasonable to expect that most of East Asia will be democratic.”

Predicting China

In China, in fact, Vaclav Havel has already inspired an entire generation of civil liberties advocates, including the imprisoned Nobel Prize winner Liu Xiaobo.

Liu’s “crime” was to have authored a Charter 08, written in 2008 and modeled on Havel’s Charter 77, calling for democratic reforms in China.

I’m leery of sweeping predictions about the future, particularly when it comes to China, but I’m also mistrustful of the idea that some societies are impervious to the pressures for democratic change that South Korea and Taiwan experienced more than two decades ago.

During the recent presidential election in Taiwan, millions of mainland Chinese followed the election through the Internet, with microbloggers avidly debating the virtues of a Chinese democracy just offshore.

And the closely contested election gave rise to a call for “real elections” from many Chinese who for their entire lives have known only one-party rule.

Dan Southerland is RFA's Executive Editor.