On Nov. 28, Vietnamese police arrested Nguyen Van Trinh, the chief-of-staff to the country's Deputy Prime Minister Vu Duc Dam. He was the second chief of staff to a deputy prime minister who has been arrested in the past few months.

The arrests were ostensibly for corruption, both involving scandals during the Covid-19 Pandemic, but in a country like Vietnam where corruption is rife, and investigative/prosecutorial resources are so limited, all such cases are highly political. These arrests shed light on how elite politics are played and how they will shape the leadership moving forward.

In 2020, Deputy Prime Minister Vu Duc Dam was a national hero, in charge of Vietnam’s stellar covid-19 response. Vietnam had mobilized society, called on combatting the virus as a patriotic struggle, sealed its borders, enforced quarantines, and superb and consistent public health messaging.

Dam was in charge of the nationwide response. And many were surprised when, at the 13th Party Congress, the quinquennial leadership turnover in January 2021, he was not elevated from the Central Committee to the 19-member Politburo. Many recall the crushed Dam, caught on film leaving the Congress. And for many Vietnamese that a competent technocrat, who helped the country have the only positive economic growth in Southeast Asia in 2020, was passed over in favor of political hacks, was disheartening.

Things quickly went south for the new government that came to power in early 2021. Vietnam's low covid numbers made it complacent about vaccine acquisition, and the country was hard hit by the Delta and Omicron variants, prompting Ho Chi Minh City and other Mekong delta cities to go into lockdown. Vietnam ended its own "Zero Covid" strategy.

At this time, Viet A, a medical testing firm won a license to produce inferior covid test kits, which it sold to all levels of the government at a 45 percent markup, wracking in $172 million in profits.

Viet A's CEO admitted to paying over $34 million in bribes. The investigations brought down 90 people, including two Central Committee members, one a former Minister of Health, the other a former Hanoi mayor. Two senior military officials were also prosecuted. Over a hundred have been investigated.

Dam’s chief-of-staff was accused of helping Viet A register and receive government contracts.

![Vietnam's Deputy Foreign Minister To Anh Dung [left] and Nguyen Quang Linh, the assistant to Pham Binh Minh, now Deputy Prime Minister, were arrested this year in connection with the scandal-ridden endeavor to repatriate Vietnamese nationals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Credit: Police [left]; Ministry of Public Security](https://www.rfa.org/resizer/v2/4U4MQXPP5UKFH5BZ7KFMS62YIA.jpg?auth=0820ef098e23f5671dbbef7bc003d0aa814cd8c46c1d1c5413a8e72d9719dfb3&width=800&height=298)

Scandal-laden repatriation flights

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs was in charge of organizing repatriation flights for Vietnamese nationals during the pandemic, which became a completely scandal-laden endeavor. 70,000 citizens returned from 60 countries in this program.

In all some 22 diplomats have been investigated with several arrests. Others, including the owner of a travel agency that was used in the scheme, have also been arrested. The highest-ranking official, Deputy Foreign Minister To Anh Dung, was arrested in April 2022, expelled from the party, and prosecuted.

On 27 September, authorities arrested Nguyen Quang Linh, the assistant to Pham Binh Minh, now Deputy Prime Minister, but formally the minister of Foreign Affairs, on whose watch the scandal unfolded.

Minh is a member of the elite 18-member Politburo. And due to party rules, he’s one of six people eligible to become the Party’s General Secretary, however unlikely. Minh was also tipped to become president, a largely ceremonial and diplomatic role.

In the 12th Central Committee, two Politburo members were sacked, one of whom was stripped of his party membership and put on trial. So there is a precedent to go after senior leaders. As mentioned above, two Central Committee members were stripped of their membership and prosecuted in 2022.

But what do these arrests say about the nature of Vietnamese politics?

First, Vietnamese politics are based on patron-client ties.

If individuals like Minh and Dam are too senior or if going after them would cause too much intra-party dissension, targeting their top aides is a very effective tool. Given the routine use of torture by the police, which can result in in-custody death, the aides will talk. And that may be enough.

Anti-corruption as a political weapon

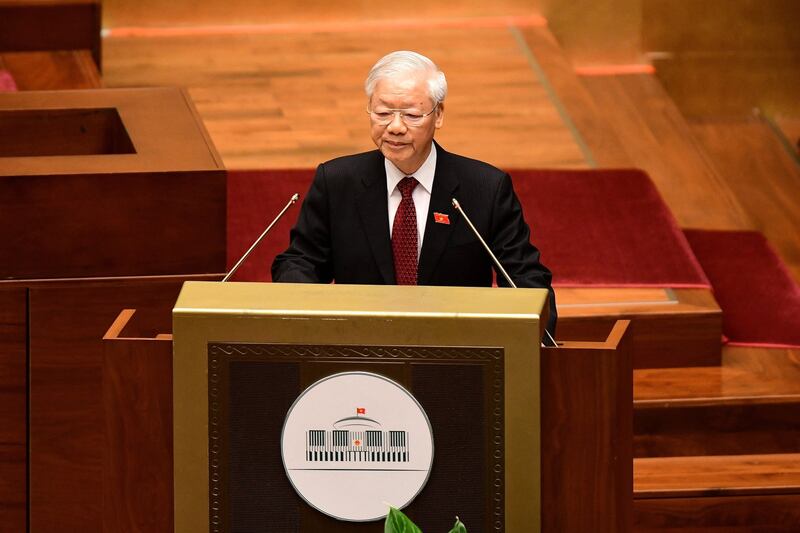

In the unlikely case that they both survive until the 14th Party Congress is held in early 2026, their wings are clipped, and they will pose no threat to General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong who is maneuvering to have his protege elected.

The 78-year-old Trong, now in his third term, has already received two age waivers. He was expected to step down before the 14th Congress but shows no signs of retiring. Though he has made counter-corruption the theme of his leadership, constantly warning that it threatens the VCP’s legitimacy, the reality is that he has wielded anti-corruption as a political weapon.

Trong neutralized former Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung at the 12th Congress in 2016, and then went after Dung’s proteges, including Politburo member and rising political star Dinh La Thanh.

Ahead of the 13th Congress, Trong unleashed the head of the Central Inspection Commission, Tran Quoc Vuong on political rivals. Here Trong may have overplayed his hand.

Vuong was his own heir apparent to succeed him as General Secretary. With a shared threat, various factions united to prevent that from happening, and Vuong was not only not elected General Secretary but voted off the Politburo altogether.

Trong appears to have learned his lesson and has been more restrained in in targeting senior leaders, especially his rivals. He can’t give them another reason to rally against him. So Trong has set his sights on the aides and protégés of rivals, coming close enough to politically emasculate them.

It’s not clear whether Trong will last until 2026, but this time around, he’s laid the groundwork for his protege to be elected General Secretary.

According to party statues, you can only be General Secretary if you have served two terms on the Politburo, leaving six eligible candidates: President Nguyen Xuan Phuc, Prime Minister Phạm Minh Chính, National Assembly chief Vương Đình Huệ, Minister of Public Security Tô Lâm, Vietnam Fatherland Front Chief Trương Thị Mai, and Deputy Prime Minister Phạm Bình Minh.

Minh is out of the running for the corruption scandal, while To Lam has his own scandal from his $2,000 gold steak fiasco, and is vying for the presidency once his term as Minister of Public Security expires. Truong Thi Mai has the wrong chromosome. President Phuc, who vied for the post in 2021, has allegations of corruption hanging over him and may bow out to save himself. The last thing Phuc wants is a corruption investigation into him, his family, or close associates.

That leaves Prime Minister Chinh, who would be acceptable to Trong, or his preferred choice and protege, Vuong Dinh Hue.

Either way, Trong has used corruption investigations to neutralize opposing factions and individual rivals. To a degree he was thwarted in 2021; he won’t be in the run-up to 2026.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or RFA.