Vietnam has been riding very high the past few years with its superlative initial handling of the Covid-19 pandemic that kept its factories open and as the single biggest beneficiary of corporate supply chain diversification out of China.

Vietnam realized 8.5% growth in 2022 and had commitments of $22.4 billion of foreign direct investment (FDI). Pledged FDI by September 2023 already reached $20 billion.

A stream of high-level foreign visitors - including U.S. President Joe Biden - have come to court the leadership in Hanoi. Apple moved a supply line to Vietnam, Lego is building a solar-generated plant, and other chip manufacturers have made announcements about establishing production in Vietnam.

Yet, growth for the first six months of 2023 was only 3.72%, half the target. Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh announced that the target for 2023 remains 6.5% but the Asian Development Bank, IMF and Singapore’s UOB have all sharply lowered their predictions closer to 5%.

While Vietnam has benefitted from supply chain diversification, that’s also made it over-dependent on exports; Exports reached 93% of GDP in 2021. Exports fell for five consecutive months in 2023, the longest slump in 14 years.

Exports to the United States in the first nine months of 2023, were down 24% compared to the previous year, which had a large impact on their overall trade balance. Vietnam runs enormous trade deficits with China, as its manufactured goods are dependent on imported components.

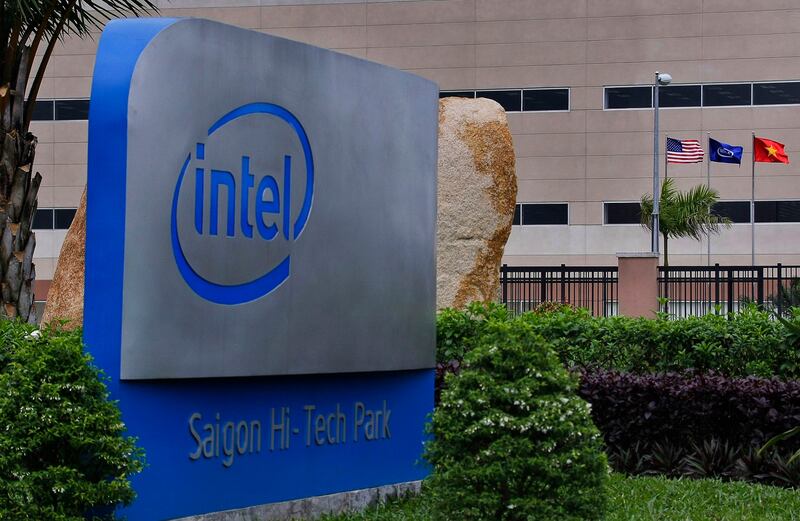

Recent announcements by two important foreign investors, Intel and Ørsted, should also be red flags for the leadership.

Jumping the gun

Intel opened their chip assembly and packaging plant in 2010 and in 2021, increased their investment to $1.5 billion.

In early 2023, there were unconfirmed reports that the firm was planning a $1 billion expansion. Vietnamese leaders were clearly expecting that and more. In February, the Vietnamese government jumped the gun in announcing a $3.3 billion investment from Intel.

The firm’s CEO told Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh in a May 2023 meeting in Hanoi that the firm still had plans to invest in the country.

Despite the fanfare around Biden's September 2023 trip to Vietnam, the passage of the CHIPS Act, and Chinh's whirlwind tour of Silicon Valley in September, Intel announced that they would not be expanding in Vietnam in the foreseeable future.

Both sides tried to do damage control. Intel reiterated that they had “never made any official announcement of a new investment.” But clearly something was amiss.

In June 2023, the Danish renewable energy giant Ørsted announced that it was leaving Vietnam's wind market, stating that "Our business ethics have met hurdles."

Vietnam, according to the World Bank, has the fastest growing electricity market in Southeast Asia. And it also has the fastest rate of renewable energy growth in the region. With its long coastline, Vietnam is thought to be the largest market for wind power in Southeast Asia, an estimated 600GW.

Ørsted signed an agreement with T&T, a sprawling conglomerate, in 2021, with an ambitious target of investing in 21GW of offshore wind by 2030. In August 2022, the joint venture announced two offshore wind farms off Ninh Tuan province. In May 2023 it had signed a contract with a division of the state-owned oil company to build foundations for its turbines.

Unaddressed systemic issues

So the country that is trying to attract more semiconductor production and more investment in its renewable sector has seen leading global players equivocate or walk away. What’s going on?

While it's incorrect to say that Vietnam is no longer a darling of foreign investors, the country has no shortage of challenges and issues that will ensure that it doesn't reach its full potential and perhaps be caught in the middle income trap.

There are five interrelated things worth noting.

First, Vietnam's electricity supply remains erratic. Last summer's heat waves resulted in daily brownouts at many industrial estates in the Hanoi-Haiphong corridor. The government called on firms to reduce their energy consumption.

If you want to be the “plus one” as companies seek to diversify supply chains, then you have to get basic infrastructure right.

While there was great relief that Vietnam finally produced its long awaited power development plan (PDP-8), in May 2023, it took years to negotiate and was highly contentious; the prime minister didn’t even sign off on it.

PDP-8 remains short on details and it watered down Vietnam’s commitment to reducing its dependence on coal fired power plants. The government is not even close to getting their implementation plan completed, and the grid remains antiquated and underdeveloped.

Although Vietnam joined the $15.5 billion Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) program in 2023 to wean itself off of coal, and has committed itself to carbon neutrality by 2050, it’s been slow to provide the donor community with concrete plans.

It hasn't helped that it has arrested six climate activists on trumped up charges who were presenting plans to help the government reach their carbon neutral goals.

Corruption worries

The regulatory framework remains both unclear, contradictory, and oftentimes undeveloped. Ørsted indicated concern that the power purchase mechanism is still not in place, and unlikely to be agreed upon anytime soon.

Second, there are real human capital concerns. With Samsung, Amkor, Synopsis, and others rushing into Vietnam’s young semiconductor industry, there are already shortages of trained engineers and designers. Vietnam has an estimated 5,000 chip engineers, and it will take years to get more trained.

Third, corruption remains endemic. The most recent scandal, an $12.5 billion embezzlement scheme at Saigon Commercial Bank, highlighted the lax oversight and corruption within the banking sector.

Ørsted’s announcement made indirect mention of corruption.

Fourth, Vietnam is less politically stable than what meets the eye. The three politicians most trusted by the international business community were purged in December 2022 to February 2023 in the “Blazing Furnace” anti-corruption campaign of Communist Party of Vietnam General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong.

None was directly tied to corruption, and the moves against them were seen as being politically motivated. Throughout 2023, there were rumors that the Prime Minister himself was in fear of losing his job.

There have now been two CPV Central Committee Plenums that have been unable to come to a consensus on who to fill the two vacancies on the Politburo. And infighting ahead of the 14th Party Congress, expected to be held in January 2026, is already underway.

Finally, policy making remains slow and cumbersome and no one is expecting a bold response to the slowing economy ahead of the Party Congress.

Vietnam still has a lot going for it, but its growth and attractiveness as a destination for foreign investment are not preordained. In a very competitive global landscape, Vietnamese policy makers have to be responsive.

The recent signals by two global industry leaders suggest a lack of confidence in Vietnam's leadership to provide sound corruption-free economic stewardship.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or Radio Free Asia.