Vietnam’s support for Russia during the latter’s illegal invasion of Ukraine is not surprising due to the long historical relationship between the two states, even though the justification for the attack creates a very dangerous legal precedent for Hanoi, coping with a territorially aggressive neighbor of its own. Russia is a “strategic comprehensive partner,” many ranks above the United States in Hanoi’s diplomatic hierarchy. But Russian losses put the government in a very awkward position vis-à-vis its public who often use foreign policy as an oblique means to criticize the Communist Party.

Vietnam will forever be indebted to Russia for its support during the American War. In particular, the provision of some 7,600 advanced surface-to-air missiles denied the United States uncontested airspace. During Vietnam’s occupation of Cambodia in the 1980s, the Soviet Union provided significant amounts of weaponry and economic support and was one of the diplomatically isolated Hanoi’s few allies.

Though economic aid and military assistance ceased by 1991, and the leadership in Hanoi was aghast at the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia became the main supplier of Vietnam's military modernization program. At its peak, 80 percent of all Vietnamese military equipment was Russian. That number is coming down, but Russia still accounts for 74 percent of Vietnam's imported weaponry, even amidst a diversification effort.

There remain close intelligence ties as well. Although the Soviets withdrew from their naval base in Cam Ranh Bay in 1991, they maintained their signals intelligence facility there, which remains operational. There continues to be close intelligence sharing and training. This fact is not lost on the 19-member Politburo, five of whom came out of the Ministry of Public Security.

On the diplomatic front, Vietnam largely blamed Ukraine for bringing the war on itself, by not managing great power competition correctly. The thinking went, that if Kyiv had Hanoi’s “4 Nos and a Maybe” foreign policy, they wouldn’t have gotten themselves invaded.

But most of all, until the war, Putin was held in high regard in Vietnam by both the leadership and public alike. For a country perpetually torn between the United States and China, Putin’s Russia provided an interesting alternative pole that at least appeared self-reliant and somewhat independent.

Cool with it

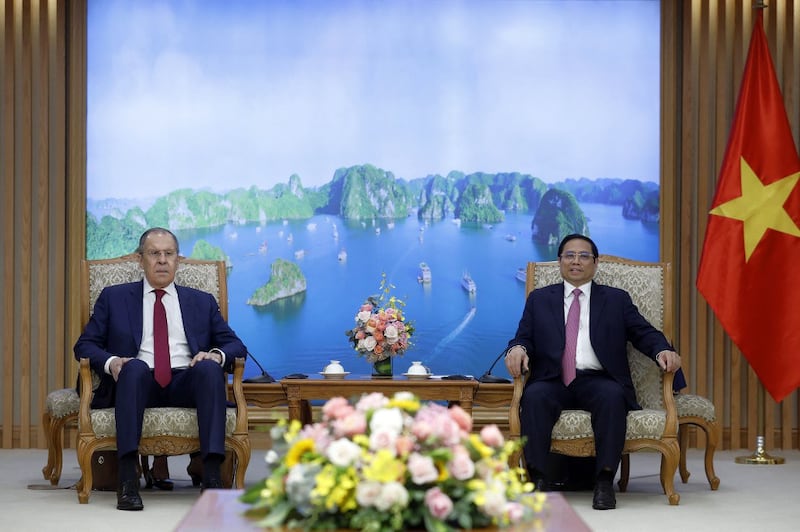

At a time when Russia is increasingly diplomatically isolated, Hanoi has continued its embrace. Hanoi welcomed foreign minister Sergei Lavrov ahead of the G20 foreign ministers' meeting in Indonesia. Lavrov reiterated Hanoi's concerns about "non-interference" and "sovereignty", playing up fears of U.S. meddling in Vietnam's domestic politics. Russia, he reminded his interlocutors was a benevolent power committed to Hanoi regime security.

Vietnam abstained in the vote to condemn the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but supported Russia in its bid to stay on the Human Rights Council. Vietnam also sent a military team to participate in Russia's annual " army games."

This prompted U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken to cancel his visit to Hanoi. This was a very clear signal of displeasure towards a government that has been showered with attention since 2021, including visits by the Secretaries of Defense, State, and the Vice President, amongst others.

U.S.-Vietnam bilateral trade in 2021 was $112 billion, compared to a mere $5.54 billion with Russia. The United States is now Vietnam’s largest export market - accounting for 25.6 percent of all exports in 2021, and a source of high-tech investment.

The United States has already quietly sanctioned one Vietnamese firm for evading sanctions for Russia.

Media carry disinformation

Vietnam's state-controlled media was not as neutral as some suggest, and tended to be more pro-Russian from the start. Ukraine had a really hard time getting their message out amidst Russian disinformation.

There was some pro-Ukrainian sentiment in Vietnam’s lively Facebook groups. Some people were very sympathetic to the country being victimized by a rapacious neighbor. Others understood the legal precedent that China would take from Putin’s justification for war.

But by and large, the online sentiment was a pro-Russian and explicitly anti-western "echo chamber". Two Vietnamese researchers who studied the 28 Facebook pages and groups found that there were eight pro-Russian out of patriotism and nostalgia, 18 that were patriotic/conservative and anti-western, and finally those that simply presented pro-Russian news takes.

Force-47, the Vietnam People’s Army’s (VPA) 10,000-man cyber watchdog and shaper force, has been active in blocking pro-Ukranian and anti-Russian sentiment while pushing the Russian narrative through its own network of influencers.

But Russian forces are now being humiliated and in the midst of a strategic collapse. Kyiv's offensive has routed Russia in northern and eastern Ukraine. Over 1,500 square miles of territory have already been recaptured, as Russia was forced to implement their "tactical withdraw plan". Putin had to address Chinese President Xi Jinping's " concerns" at the Shanghai Cooperation Organization's recent summit.

The setbacks in Ukraine forced Putin to order the country’s first military draft since the second world war, a "partial mobilization" of all reservists and able-bodied veterans. The order prompted demonstrations across Russia and triggered an exodus of fighting-age men to foreign countries. Resistance to the draft is further demonstration of President Putin's deteriorating control, and the rapid deployment of untrained troops is a sign of the regime's desperation.

For Hanoi, the real concern is that a greater questioning of Russian capabilities and Putin's leadership will quickly morph into anti-party discussions. Government pundits have doubled down, and been dismissive of Russian losses.

And that’s for a reason: Foreign policy debates have a nasty habit of turning into opportunities to question the leadership in Vietnam.

Soul searching

Russian losses should prompt concerns in Hanoi. Their military is dominated by Russian equipment. The VPA is still highly influenced by Soviet doctrine. Their military remains top down and unable for local commanders to seize the initiative. The VPA remains a party army, legally bound to defend the regime, not the state.

And Hanoi should be very concerned about the deleterious effects of corruption on force readiness, logistics, and operations. The once vaunted VPA has been caught in a number of corruption scandals of late, including a Covid-19 testing scheme, a Coast Guard procurement and protection racket scandals, and land. Russia's military was hollowed out by endemic corruption, something that's become normalized in Vietnam.

Finally, Hanoi has to be alarmed that Russia's very real losses will impact the VPA's own procurement. Russia must quickly recapitalize its forces, and do so in the face of continued sanctions and shortages of precision milling equipment and semiconductors. There will be a shortage of Russian spare parts for years, let alone delayed delivery schedules for new equipment and munitions. This has an immediate impact on Vietnam's security.

Kyiv’s strong defense and now successful offense put Hanoi in a bind in one final way: Ukraine’s success was borne out of knowing Soviet doctrine, but adapting Western force structures, tactics, doctrine, and some western equipment. And what made all of that possible was their democratization. If anything Ukraine presents a much more compelling example of a state successfully defending itself against an aggressive great power on its borders. But that is an inconvenient truth for Hanoi.

Zachary Abuza is a professor at the National War College in Washington and an adjunct at Georgetown University. The views expressed here are his own and do not reflect the position of the U.S. Department of Defense, the National War College, Georgetown University or RFA.