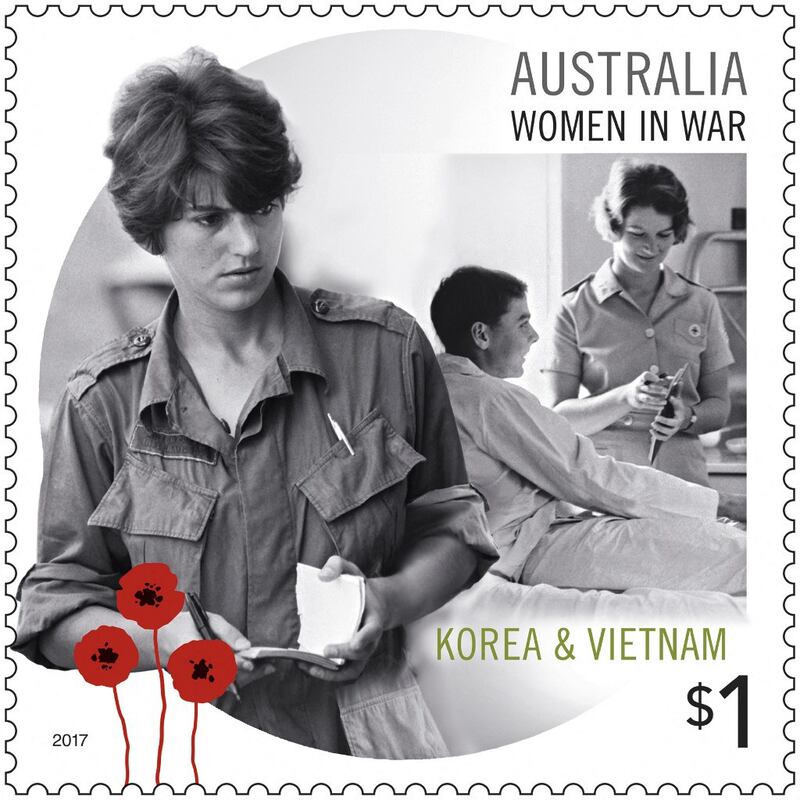

During the Vietnam War female war reporters and photographers performed admirably but often received less recognition than their male counterparts.

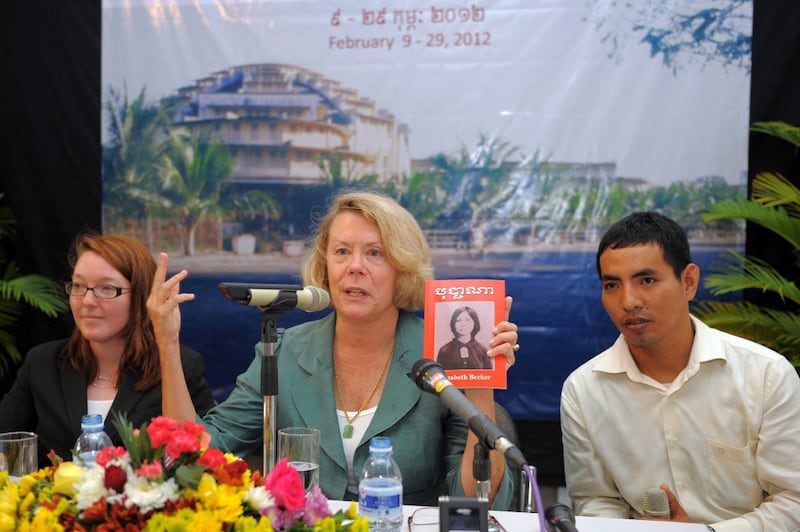

Elizabeth Becker, who reported on the war in Cambodia in the early 1970s, has written a new book that sets the record straight.

In her book titled You Don't Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War, Becker focuses on two female war correspondents and a female photographer.

I should state early on that I knew both of the war reporters as well as the author, whom I consider a friend.

I only wish that I’d had a chance to meet the photographer, a French citizen named Catherine Leroy who loved nothing better than to be taking photos of U.S. Marines in the middle of a firefight.

Frances FitzGerald, the second of the three, wrote for The New Yorker and other magazines. She has written several books, most notably Fire in the Lake, which deals with the Vietnamese and the Americans involved in the Vietnam War.

While most American reporters were focused on covering the American military forces, FitzGerald focused on getting to know the Vietnamese from both sides. She arrived in Vietnam in February 1966.

And then there was Kate Webb, who went on to become perhaps the most famous of the three after she arrived in Vietnam and began working for United Press International (UPI), which was my employer at the time.

Some of the most powerful passages in Elizabeth Becker’s book deal with the challenges that Kate Webb faced in a male-dominated world as well as with her achievements.

Kate arrived in Saigon in 1967 at age 23 on a one-way ticket from Australia, where she had resigned from a job as a junior copy editor. Kate went to UPI looking for a job.

Bryce Miller, the UPI bureau chief at the time, asked “What the hell would I want a girl for?”

Bryce’s attitude was typical of an era when women war reporters were rare.

But he gave Kate some trial assignments and quickly came to respect her.

When I first arrived in Vietnam in early 1966, UPI sent me out to cover combat operations, including stints with the 1st Cavalry Division and U.S. Marines operating in the northern part of South Vietnam.

Then I got a huge break. Gene Risher, who had replaced Bryce Miller as the UPI bureau chief, encouraged me to do analytic pieces, or “think pieces,” as we called them.

Partly because I could speak French, which was still useful then, Gene assigned me to cover Vietnamese politics as well as the non-military aspects of the war, including war victims, refugees, and the “pacification” program.

I had been complaining that we weren’t covering the South Vietnamese aside from some of the biggest military clashes that they engaged in.

Now thanks to Gene, I had a chance to cover the country, not just the war. It opened up a whole new world of uncovered stories. At one point, I took a break on my own dime to study Vietnamese with a Vietnamese tutor.

After Kate Webb arrived in Saigon in 1967 her first job was to work as my assistant on the “political staff,” as she called it.

But that staff was just the two of us with UPI in Saigon out of a total of 10 reporters and four or five photographers.

Kate Webb becomes famous

Kate went on to cover all aspects of the war for six years for UPI, including a stint in Cambodia in 1971 when she was captured by the Viet Cong and held prisoner for 23 days. While in captivity Kate developed a bad case of malaria before being released.

During her ordeal in captivity, Kate was given up for dead. The New York Times published her obituary.

At that point, Kate Webb became truly famous.

What I remember most about Kate was her ability to get to know people wherever she went. As Kate described it in a book written by women war reporters, she tended to find her friends among the Vietnamese “from MPs, journalists, priests and students to soldiers, bar girls, and street kids.”

In that book titled War Torn, Kate said that in later years when her thoughts returned to Vietnam, it was often to Captain Truong of the South Vietnamese Army's 1st Infantry Division. The division was often ranked as the Vietnamese Army's best along with the marines and paratroopers.

The captain’s soldiers were, unlike the American GIs, in it for the duration. His company operated at night without helicopter support. The men carried their wounded out on foot.

In her book, Elizabeth Becker says that I sent Kate Webb out on high-danger night patrols. I don’t remember doing that. But I do remember Kate telling me about Capt. Truong and her desire to go on a patrol with him. I said okay, but you must pull back if you sense any danger.

Kate was there on a patrol when Capt. Truong was wounded. When his number two man was hit, Kate helped to carry him on a stretcher back to headquarters, where his arm was amputated.

I should add that I went out on a patrol with a U.S. Marine squad at the end of January 1966, which may have been one of the stupidest things that I ever did during the war. The Marines had lost their squad leader to a sniper on the same trail just the day before that.

So I didn’t serve as a great role model for anyone.

It's hard to imagine anyone better qualified to write a book about female war reporters than Elizabeth Becker.

She was a war correspondent for The Washington Post in Cambodia. She later became the senior foreign editor of National Public Radio and a New York Times correspondent covering national security and foreign policy. She is the author of two previous books, one of which dealt with Cambodia.

UPI’s amazing female reporters

I was inspired by the stories in Elizabeth Becker’s book to recall that aside from Kate Webb several outstanding women reporters based in Saigon for United Press International also worked frequently in the field.

They took the same risks as their male counterparts.

Betsy Halstead, one of the best of them, wore South Vietnamese soldiers’ combat fatigues when she went on operations with them. Bob Kaylor, a reporter who worked for UPI mostly in the northern part of South Vietnam, told me recently that Betsy was respected everywhere she went,

Bob said that he’ll never forgot going to Saigon’s Tan Son Nhut airport once with Betsy when the two of them were getting on flights to go to different destinations in the field.

Several American soldiers waiting for flights saw Betsy dressed in her fatigues. They asked Bob, “Who is she?”

They were amazed when they learned that Betsy was heading into the field while her husband, the photographer Dirk Halstead, who was with her and wearing civilian clothes was staying behind.

UPI’s Helen Gibson went through the South Vietnamese Army Airborne Division’s jump school at Tan Son Nhut and “got her wings,” as they used to say.

Helen’s husband was assigned as a reporter in Vietnam in early 1968, and she joined him shortly thereafter. They left in early 1970 after serving in Vietnam for two years.

I recently contacted Helen, who now lives in southern France, and asked her whether she felt that she got less recognition for her work in Vietnam than her male counterparts.

“I think that women did fine,” she said. “If they did a good job, they were recognized for it. I can’t remember anyone saying otherwise.