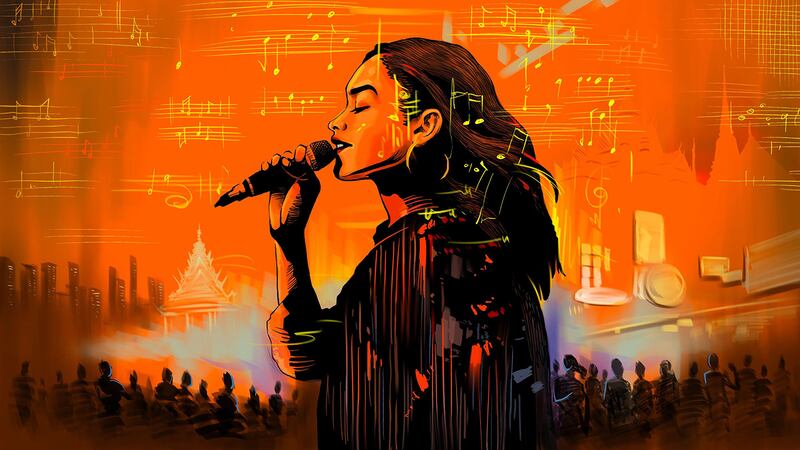

BANGKOK — Once a full-time musician who toured throughout Myanmar, indie-pop star Linnith now finds himself in vastly different circumstances –- just like so many other celebrities who fled the country after the 2021 military coup d’etat.

From his new home in Maryland in the United States, Linnith told Radio Free Asia about working as an Uber driver and trying to experiment with new music, but also generally “feeling lost.”

“In my country, I don’t have to work like this – 50 hours a week, or something like that,” he said last week.

After the coup, Linnith and many other artists took to the streets in protest. They also wrote music and posted on social media against the military dictatorship.

Subsequent crackdowns by the junta left hundreds dead and thousands in police custody as censorship and threats of violence forced many artists into hiding.

But the aftermath of the coup has also brought underground and ethnic artists into the spotlight, as widely popular anti-coup music proliferates both online and off and artists navigate a new music industry with unique challenges.

“Everything is different now, it’s not only the production, literally everything,” Linnith said, adding that he’s had to transition from making music in a major studio with a team and professional equipment to working independently.

“After the coup, I can make music in my bedroom with my laptop with one cheap mic. I don’t even have a soundproof room, you know? That’s it.”

Others are embracing the new underground nature of the music industry, where online platforms have given rise to popularity of new artists.

“My priority is politics, so I write down all these things that I think about politics that I think about in my rap,” said an underground rapper asking to be identified as T.G. “I talk about the military coup and how we should unite and fight them back to get democracy for our generation.”

New challenges

But addressing politics can be a matter of life and death.

At least three hip-hop artists have been arrested for their role in anti-junta movements, two later dying at the hands of the junta. Yangon-based 39-year-old Byu Har was arrested in 2023 for criticizing the military’s Ministry of Electricity and Energy on social media, and later sentenced to 20 years in prison.

But others have met worse fates. Rapper and member of parliament for the ousted National League for Democracy party Phyo Zayar Thaw was executed in 2022. Similarly, San Linn San, a 29-year-old former rapper and singer, died after being denied medical treatment for a head injury sustained in prison linked to alleged torture, according to a family member.

Many others have been injured protesting the dictatorship.

Like many fleeing the country to avoid political persecution and to find work, much of the music industry has also shifted outside of Myanmar.

A former Yangon-based rapper who asked to be identified as her stage name, Youth Thu, for security reasons moved to Thailand when she saw her main job in e-commerce being affected by the coup and economic downturn.

“When I came here, I was trying to stay with my friends because I have no deposit money to get a room because I need to get a job first,” said Youth Thu.

Now working at a bar in Bangkok, she’s starting to incorporate her experiences into music that will resonate with others in the Myanmar diaspora.

“I never expected these things. I never expected to be broke as [expletive deleted]. I never expected to live in that kind of hostel,” she said.

“Especially migrants from Myanmar who are struggling here, I’m representing that group so my songs will be coming out saying all my experiences.”

For those left inside the country, economic factors are also taking a toll on music production, Linnith said.

“Because of inflation, the exchange rates are horrible… All the gear, the prices are going so high, like two or three times what it was,” Linnith said. “So most people can’t upgrade their gear or if something is wrong, they can’t buy a new thing.”

Starting again

The challenges have also ushered in new music and different tastes from audiences, as well as a boom in the underground industry and in rap and grime, a type of electronic dance, artists told RFA.

T.G. said he’s seen a new appreciation for ethnic music coming from the country’s border regions, where languages other than Burmese dominate the music scene and everyday life. He’s also seen a revival of revolutionary music popularized in 1988, when student protests across Myanmar ended in a violent military coup that has drawn comparisons to the junta’s 2021 seizure of power.

“After the [2021] coup, a lot of people from the mainland, a lot of people are going to the ethnic places like Shan, Kachin, Karen and then, Karenni,” he said. “They started to realize there are a lot of people willing to have democracy, so they started to realize that ethnic people are also important for the country.”

Artists are also dealing with new feelings on a personal level. Depressed, anxious and struggling to cope with changing realities, Linnith and others have found new feelings to draw from.

“The lyrics are literally ‘I give everything, I don’t believe in anything. I’m lost.’ That’s the kind of feeling I’ve got at the moment…I wrote it in my head while I was driving, again and again and again,” he said.

“This is perfect timing, a perfect song for me…. Not just a perfect song, but the best song. It came from real feelings, real pain.”

Youth Thu says while her music isn’t inherently political, she is also writing about her new life in ways she hopes will resonate with her audience.

“I got to meet with other girls who are coming to Thailand to survive too. We have different goals, but still we are sharing lunch, sharing rooms, sharing the hostel – and they have no voice,” she said.

“I have a voice – voice means the songs. I can write a song, I can say I’m not afraid in the songs and include all these things.”

Edited by Matt Reed.