Part of a three-story series to mark the fourth anniversary of Myanmar’s 2021 coup, looking at how the military treats its own soldiers.

Min Din didn’t want to be a soldier. He joined the Myanmar military 33 years ago, seeking a steady income for his wife and his newly born son. Seven months ago, that long career came to a bloody end. The 57-year-old army sergeant was felled by a rocket fire in a rebel assault on a besieged military base in Shan state. His body was buried nearby.

Far from enjoying financial security, his wife Hla Khin is now a widow without income. She’s still waiting for a payout from his military pension.

Min Din’s grown-up son, Yan Naing Tun, who has fled Myanmar to escape military conscription, is bitter about the leaders who ordered his father into battle in the first place.

“Old soldiers like my father fought and sacrificed their lives, but their deaths did not benefit the people,” Yan Naing Tun told RFA, his eyes sharp and full of pain. “My father’s death was not worth it; he gave his life protecting the wealth of the dictators.”

Four years after the coup against a democratic government that plunged Myanmar into civil war, the military has inflicted terrible suffering on civilians. Torching of villages, indiscriminate air strikes and stomach-churning atrocities have become commonplace. Even the military’s own rank and file are paying a price.

This is a story about two veteran soldiers of the Tatmadaw, as the military is known inside Myanmar, whose bereaved families spoke to RFA Burmese about how they’ve struggled to survive after the soldiers’ deaths in combat after more than 30 years of service. All their names have been changed at their request and for their safety.

While reviled by many for its long record of human rights abuses, the Tatmadaw remains the most powerful institution in the country - and one that has traditionally offered a career path for both the officer class and village recruits.

But any appeal that a military career once had has been eroded – not just through its reputation for corruption and atrocities, but by setbacks on the battlefield. By some estimates, it now controls less than half of a country it has long ruled with an iron fist. Its casualties from fighting with myriad rebel groups likely runs into the tens of thousands.

There are growing signs it can’t look after its own.

Aung Pyay Sone, the son of Myanmar’s military leader Min Aung Hlaing, has been accused of running a predatory life insurance scheme in which all soldiers make contributions. They are also obliged to make monthly contributions to a sprawling military conglomerate known as Myanmar Economic Holdings. According to families, the life insurance scheme is no longer paying out on the death of a soldier. Families also struggle to get pension payments they are due.

A way to support a family

Another recent Tatmadaw fatality, Ko Lay, signed up for the army during what might be considered as its oppressive heyday in the early 1990s when the military was in the ascendant against ethnic insurgencies and expanding its business interests.

He enlisted soon after the country’s first multi-party democratic election. The pro-military party lost by a landslide, but the ruling junta refused to hand over power – leaving the winning party’s leader Aung San Suu Kyi under house arrest. (That’s a situation similar to now. Suu Kyi, who had led the now-ousted civilian government for five years, has been imprisoned at an undisclosed location since the 2021 coup).

RELATED STORIES

Myanmar’s forced conscription: How the junta targets young men for military service

In the Myanmar military, life insurance for soldiers isn’t paying out

Against this backdrop of democracy suppressed and the military in control, Ko Lay enlisted aged 20. He was a villager from central Myanmar’s Bago region, who had dropped out of school because his parents could not pay the fees.

His wife maintains that joining up was never a political decision. The military offered a pathway to employment and a way to support a family.

“My husband was uneducated,” his wife Mya May told RFA. “He didn’t even pass the fourth grade. His parents did not remember when he was born. When he joined the army, one of the officers looked at him and estimated his birth date and the year and enlisted him.”

Ko Lay only married in his 40s, but once he did his family moved with him every time he was transferred, which is customary. But after the 2021 coup, with fighting intensifying as people across Myanmar took up arms against the junta, they sent their 10-year-old son to live with relatives near Yangon.

At the start of 2024, with rebel forces in northeastern Myanmar gaining in strength, Ko Lay was deployed with Infantry Battalion No. 501 in Kyaukme, in northern Shan State. Mya May and her 89-year-old father Ba Maung followed him.

Under fire

In February, villagers were starting to flee the area as a military showdown beckoned. Ko Lay’s battalion was meant to be strengthened for this fight, but in reality, it numbered fewer than 200 troops, less than a third of full strength. By late June, the combined forces of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) and a People’s Defense Force unit from the Mandalay region were closing in.

Mya May said that Ko Lay was stationed on the outer perimeter of the military camp at Kyaukme. Inside the camp, Mya May, along with other wives, were put to work loading and carrying ammunition.

“My husband was stationed on the outer perimeter near a monastery. Resistance forces used the monastery as a strategic position, drilling holes into the brick walls to fire guns and launching missiles from above,” she said.

As the attack intensified, frontline soldiers, including Ko Lay, retreated into the camp. Snipers began picking them off. At 7:30 a.m. on June 27, Sgt. Ko Lay was killed by sniper fire.

Mya May never retrieved his body. She believes he was buried at a rifle range.

She and her father were now under fire themselves. As they sheltered in a building inside the base, rebel rocket fire hit the building and showered glass over them. They fled during a lull in the fighting in vehicles organized by the military that transported them and other families to another military base.

The remaining soldiers were left to fight. Within a month, their commander would be dead, and almost the entire battalion wiped out.

Struggling to get by

Mya May, her 10-year-old son, and Ba Maung are now living near Yangon with relatives. She still feels deep sorrow that she was not able to bury her husband or be with him in his final moments.

She’s also struggling to make ends meet.

It took Mya May three months to receive her husband’s pension. She now gets a monthly stipend of 174,840 kyats (about $40), with an additional 19,200 kyats ($4.30) per month for her son – which is scarcely enough to survive in Myanmar’s stricken economy. But because her husband died on the frontline, she received an additional one-off payment of 13,166,500 kyats ($3,006).

This frontline death payment was a much-touted inducement offered prior to the 2021 coup aimed at encouraging young men from poor families to sign up.

Her father, Ba Maung laments their situation after Ko Lay’s death.

“Seeing my daughter in trouble, having lost her husband and all her belongings, is deeply disappointing,” the 89-year-old said. “When she got married, she promised to support me. She is very clever. But now I can’t help her, and it fills me with great sadness.”

They’ve also been short-changed by the life insurance scheme that Ko Lay bought. For the past five years, the sergeant had paid 8,332 kyats (almost $2) a month for a policy aimed at providing for his family in the event of his death. Four months after her husband’s death, Mya May has received exactly the same amount that had been taken from her husband’s wages. Not a kyat more.

Dying in a war zone

The widow of the other fallen military veteran mentioned in this story, Min Din, who served in the same battalion as Ko Lay and also died in June, has fared even worse.

His wife Hla Khin learned from a soldier in his company that Min Din was killed in a direct hit on the battalion headquarters by a short-range rocket. He was buried near the central gate of the base.

“Due to the dire situation in Kyaukme, we couldn’t travel there to see him or pay our respects,” Hla Khin said, adding that the best they could do was to offer alms to monks and donate 100,000 kyats to a monastery in his honor.

Her attempts to secure a military pension or any payment has so far been unsuccessful.

Applications are meant to be made in person where the soldier last served, which is no easy matter in a war zone.

“There was nobody in Battalion 501 as many people died. Almost all documents have been lost as some office staff moved out, some died and some are still missing,” she said.

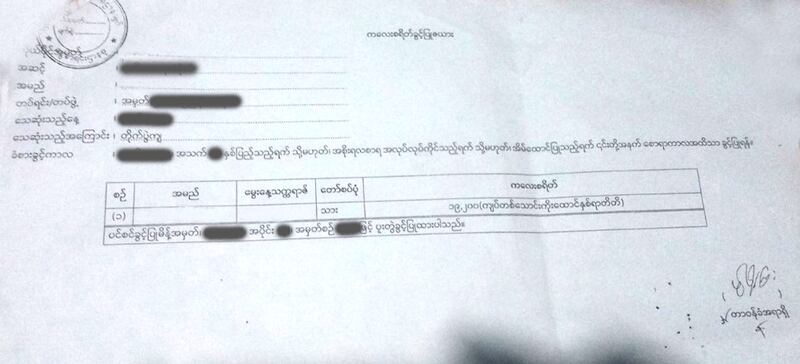

But Hla Khin, now living in her elderly parents’ house in Ayeyarwady region, said that now the necessary paperwork has been submitted. She sent a formal letter to the commander of another battalion where some of the soldiers and families have relocated. She’s waiting for a response.

Her plight is compounded by the knowledge that her husband had been desperate to retire from the military for years before his death. Months before the 2021 coup, Min Din, then aged 54, had made that request because of high blood pressure and a heart condition. He went to the army hospital at the cantonment city of Pyin Oo Lwin but was told he would have to wait until he was aged 61 to retire.

Instead, he ended up deployed on the frontline of the junta’s fight against the rebels – first at Laukkaing, a strategic town on the border with China, where junta forces surrendered under a white flag. After that humiliation, Min Din requested discharge again, and again was denied. He was then redeployed to Kyaukme, where he died.

Holding onto hope

Min Din’s eldest son, Yan Naing Tun, 33, said he is filled with overwhelming sadness. He remembers his father as kind and someone who deeply cared for his children. The family often lacked food, and he recounted his father once donating his own blood to earn some kyats to buy food and cook for them.

Like many of his young countrymen, Yan Naing Tun has voted with his feet, fleeing Myanmar for Thailand to avoid the draft and fighting for the “dictators” he says are only interested in protecting their wealth.

“There are countless young people fleeing the country, many sacrificing their lives, and countless others enduring great suffering. Our shared hope is for an end to the fighting and the arrival of peace. I am one of the young people holding onto this hope,” he told RFA.

Edited by Mat Pennington.