Part of a three-story series to mark the fourth anniversary of Myanmar’s 2021 coup, looking at how the military treats its own soldiers.

Thirty-year-old Aung Aung was arrested at gunpoint on a July morning as he left his house in central Myanmar - one of about 30 people rounded up and taken into custody in his town that day. Their crime? Being the right age to be enlisted in the struggling ranks of the Myanmar army.

Less than a month later, during a monsoon downpour, he and 10 others fled No. 7 Basic Military Training Center in Taungdwingyi township, about 70 miles from his home in Yenangchaung in Magwe region. They were clothed in little more than their underwear and were drenched in the heavy rain.

They spent two nights in the forest and had to avoid military checkpoints as they fled northward, relying on local people to provide them food, money, clothing - and directions – until they reached safety three days later.

“The journey was extremely difficult, unlike anything I had ever experienced,” Aung Aung told RFA Burmese. He requested his name be withheld as he remains at large from the military. The punishment for avoiding conscription is up to five years in prison; those who abscond from the military after enlistment could face the death penalty.

It’s not an unusual story in Myanmar. Since the ruling junta declared national conscription in early 2024 for men aged 18-35 and women aged 18-27, growing numbers of men are being forced into the army.

The military’s ranks have been depleted in the civil war that has ensued since army chief Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing launched a coup four years ago against an elected government. The recruits to fill the ranks typically come from poor families that are unable to pay off officials to avoid conscription.

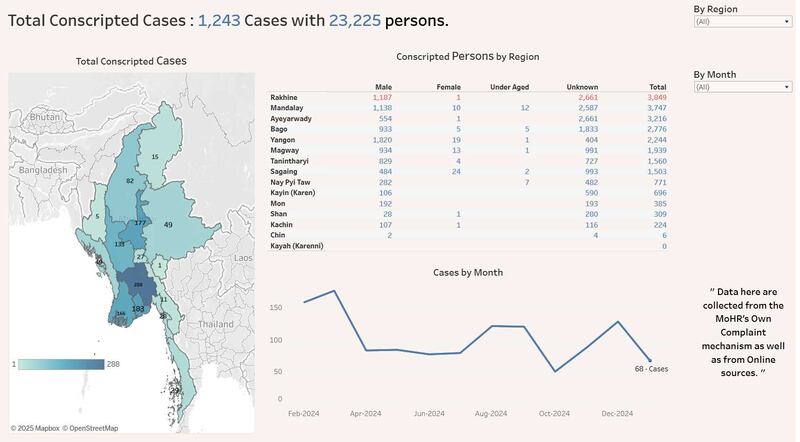

The shadow National Unity Government, formed by pro-democrats ousted from power in the coup, says that 23,000 people have been conscripted against their will since the start of 2024.

But the problem actually pre-dates the conscription law.

Killed in action

In November, the relatives of Min Khant Kyaw, 23, got a call out of the blue from authorities that he’d been killed in action. He’d been missing for three years, and it was the first they’d learned that he was in the Myanmar army.

Authorities offered little information. No details about how, when and where Min Khant Kyaw, who had been living in Yangon, died. They were just told that he was dead and the army would provide his next-of-kin with some benefits. It was only because his national registration card was found in his shirt pocket that authorities were able to contact next-of-kin in his native village.

His uncle, Lu Maw, recounts the story with sadness and anger. He had raised Min Khant Kyaw since age 7 after he was orphaned during the massive Cyclone Nargis in 2008 that devastated the Ayeyarwady delta and claimed the lives of his parents and three siblings.

Lu Maw is convinced that his nephew was forced to enlist.

“None of us, no one in our family, knew he had joined the army,” he told RFA Burmese.

“After asking all his relatives, we concluded he didn’t join the army of his own will. If he did, his relatives and everyone close to him would have known. We all knew nothing, but the authorities just informed us he died on the frontline,” Lu Maw said.

“I would not complain if Min Khant Kyaw had joined the army on his own account, but it was not like that. He was dragged into it.”

The Myanmar military has a record of duping recruits and of forced recruitment. The International Labor Organization reported the practice in the 1990s, a time when the military was in the ascendant and was seeking to boost its ranks.

Its need for recruits has become far more acute since the 2021 coup. The ruling junta has suffered mounting losses on the battlefield and has lost control of most of the country.

RELATED STORIES

‘My father’s death wasn’t worth it’: Poverty awaits families of Myanmar army dead

In the Myanmar military, life insurance for soldiers isn’t paying out

Snatched off the street

In an analysis last year, Myanmar expert Ye Myo Hein estimated that by late 2023, it had about 130,000 military personnel – about half of them frontline troops – compared with earlier estimates of between 300,000-400,000. Anecdotal evidence suggests battalions are at a fraction of regular fighting strength.

In February 2024, when the junta enacted a compulsory conscription law that took effect in April, chief junta spokesman, Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun, indicated that about 50,000 people would be recruited by year’s end. He said women would only be drafted starting in 2025. Residents say initial steps for that have now begun.

There’s no reliable count of how many people have been drafted so far. What is clear is that conscription has accelerated the exodus of able-bodied people from Myanmar. It’s also fueled a cottage industry of graft where families pay administrators the equivalent of hundreds, even thousands, of dollars to avoid the draft.

Even more sinister is that people are being snatched off the street both in cities and rural areas, multiple sources say.

Data collected by RFA showed a spike in youth arrests in Yangon, Mandalay, Naypyitaw and Bago in December. The spike appeared connected to clandestine operations at night, which residents described as “snatch and recruit,” by men wearing plain clothes and driving private vehicles. RFA reporting indicated 250 people were caught in the dragnet in those four cities in a single month.

Zaw Zaw, 27, lives outside the big city. He’s from Salay town in Magwe region. He told RFA Burmese that he was caught in a night raid on his home in early July. He was taken to the local police station before being sent for a medical at another town in the region, Chauk.

“Even those who were mentally unfit passed the test, as it seemed they accepted everyone regardless of their condition,” said Zaw Zaw – not his real name as he wanted to protect his identity.

“When I arrived at the training center, they confiscated everything my family had given me: clothes, watches, phones and money.”

Like Aung Aung, he was at No. 7 Basic Military Training Center in Taungdwingyi, and was among the group that escaped, heading toward an area controlled by an anti-junta People’s Defense Force.

No option but to enlist

Forcible recruitment takes different forms. Not all are snatched off the streets. Others are simply presented with little option but to enlist.

Moe Pa Pa, a mother of three living in Kungyangon township in Yangon region, says her missing husband, Ye Lin Aung, 29, signed up because he couldn’t afford to bribe his way out of conscription.

“He said that if he did not go this time, the ward administrator would force him again and again. I told him not to go, he should stay and work here so at least we wouldn’t run out of food. I strongly discouraged him, but he went anyway.” she said.

She last saw him, for a 15-minute conversation, just before he was shipped out to the front line in Rakhine state, where junta forces have taken a battering from the rebel Arakan Army.

“The ward administrator told my husband he would pay us 500,000 kyats ($110) up front. He also promised to pay 310,000 kyats per month while my husband was undergoing three months of training, with payments to be made monthly,” Moe Pa Pa told RFA.

All she’s seen is the bonus, no salary.

“He called me two or three times after arriving at the front line in Buthidaung and Maungdaw,” Moe Pa Pa, referring to two battle zones in Rakhine state. “He said he would transfer his salary, but since then, I have been unable to contact him. He never sent his payment, and we have been out of contact ever since.”

She suspects he’s dead. Phone calls made from the Rakhine front line stopped six months ago.

Other RFA Burmese journalists contributed reporting. Edited by Ginny Stein and Mat Pennington.