Read RFA coverage of this topic in Burmese.

It was just over a year ago that 8-year-old Chit Zaw was playing at his home in northern Myanmar when the junta jet fighter roared overhead.

His parents had no time to think — they simply picked him up and fled, without a chance to take any of their belongings. Bombs from the jet set their house ablaze, and destroyed everything they owned.

“My toys were destroyed in the fire,” Chit Zaw said from a camp for internally displaced persons. “They were left behind at home and I feel like crying all the time.”

His toys were “like my friends” — each with their own precious memories for him — and now, it’s too difficult to get new ones, he told RFA Burmese.

Every day, his parents must travel around 50 kilometers (30 miles) to the town of Monywa to take on odd jobs. Between the cost of transportation and the irregularity of work, they can’t afford to buy toys for him, let alone textbooks for school.

“My parents don’t have money, so they can’t afford it,” he said, adding that he knows he can’t ask them for what he really wants. “I wish I could play with Power Rangers toys and robots.”

Children endure ‘heaviest toll’

Chit Zaw’s story is a common one for children in Myanmar’s conflict zones since the military seized control of the country in a February 2021 coup d’etat, sparking a civil war that has lasted more than four years.

“Children are increasingly bearing the devastating consequences and enduring the heaviest toll of violence, displacement, and disruption to critical services like health and education, putting their survival and well-being at grave risk,” the United Nations Children’s Fund, or UNICEF, said in a report.

The U.N. estimates that nearly 20 million people are in need of humanitarian assistance across Myanmar — just over one-third of the country’s 55 million people.

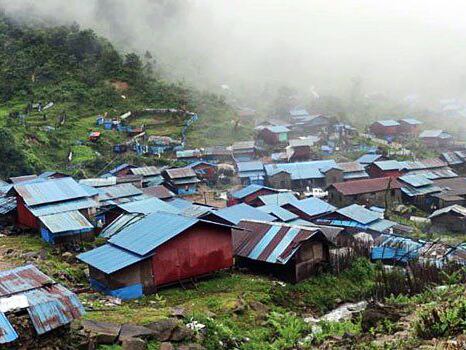

Around 3.5 million are classified as internally displaced people, or IDPs, who struggle to access food, shelter and medical assistance, and UNICEF estimates that around one-third of those uprooted are children.

Schools, hospitals and playgrounds “are now ravaged by airstrikes, landmines and violence,” it said. More than 750 children were killed or maimed in the war last year, “and the toll continues to rise.”

Meanwhile, nearly 5 million children are not accessing an education, UNICEF said, making them susceptible to risks including forcible recruitment by conflict actors, child labor, early and forced marriage, and exploitation.

The agency counts at least 55% of Myanmar’s children as “living in poverty” as displaced families struggle to meet basic needs.

‘All we feel is fear and hatred’

Taken together, kids in Myanmar are “losing their childhoods” too soon, according to experts.

They told RFA that while shelter, food and safety are fundamental needs, their mental health should not be ignored.

Thoon, a 13-year-old girl whose family fled Monywa to a camp in Depayin township, described to RFA how the near-constant threat of airstrikes has left her traumatized.

“I’m always afraid that planes might come and attack while I’m outside, so I stay indoors and draw,” she said. “I don’t feel safe outside, which is why I never stray far from home, even when I do play. I used to love playing, but now I no longer want to.”

Thoon said her family ended up in the IDP camp after their home was set on fire by junta troops, forcing them to move into her grandmother’s home, which later was also set ablaze and destroyed.

“When her house burned down too, we built a new house for ourselves,” she said. “We only spent one night in that house. The next day, neighbors warned us that soldiers had entered the village, so we had to flee again.”

“We couldn’t take much with us,” Thoon said. “The house we had just built, where we had spent only one night, was burned down along with all our belongings.”

Thoon told RFA that all she wants now is to “be safe” and go back to the way things were in Monywa before the military took power.

“Back then, when we saw soldiers, we greeted them, and they greeted us back,” she said. “We respected them because they were protecting our country. But that respect has vanished. Now, all we feel is fear and hatred.”

Prioritizing children’s needs

Children who live in fear of violence are highly susceptible to post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, according to Myanmar’s free mental health counseling program Taipinphaw.

Playing and toys are not simply fun but also a form of psychological therapy for their development, it said.

Taipinphaw, which is operated by psychologists and volunteers under the Ministry of Women, Youth and Children Affairs of Myanmar’s shadow National Unity Government, or NUG, urges caretakers to “make space” for children to be able to play freely, to help them express their feelings and reduce their trauma.

“For children forced to flee their homes and loved ones, owning toys provides a sense of belonging,” said Director Saw Thahe Sree. “These toys help them develop a sense of attachment and ownership, which plays a crucial role in building their resilience by giving them something to protect.”

Phu Pwint Wai, the head of the Anya Pyit Tine Daung Lay Myar youth organization, which assists displaced persons, noted that as parents in Myanmar focus on providing food and safety for their families, many children cannot afford to go to school and instead find work to help pitch in.

“When parents struggle to provide food and basic necessities, they are unable to prioritize their children’s needs,” she said.

Even something as basic as toys become a luxury, she added, noting that toys are typically the first thing children ask for whenever her organization visits camps for the displaced.

‘Exhausted’ from displacement

Meanwhile, in eastern Myanmar’s Kayah state, Christiano, a 12-year-old boy, and Naw Hae Jawa, a 12-year-old girl both yearned to return to life before the war.

Both were displaced by fighting from their homes in the state capital Loikaw and forced to take shelter with their families at an IDP camp in Demoso township.

Christiano told RFA that he misses his home and is praying for the war to end.

“I wish I could see my friends and go to church with my parents once more,” he said of what he longs for most back in Loikaw.

Naw Hae Jawa said she had been living at the IDP camp for four years and is “exhausted from being displaced.”

“The living conditions are poor, the food is inadequate, and I feel deeply unhappy,” she said. “I long to go to church again, just like before, and to play with my friends once more. I desperately want this war to end. The sound of planes fills me with fear.”

Translated by Aung Naing and Kalyar Lwin. Edited by Joshua Lipes and Malcolm Foster.