As Cambodia takes over the chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations in 2022, it faces an uphill task to accelerate negotiations for a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea.

The code, which is intended to mitigate the risk of conflict in those contested waters, has been in the works for about as long as Cambodia has been in ASEAN.

The Kingdom joined the 10-nation grouping in 1999, and 2022 will be the third-time that Cambodia has held the rotating leadership of the regional bloc. It’s also the third time that Prime Minister Hun Sen, who has been in power since 1985, has held the ASEAN gavel that was handed to him from outgoing chair Brunei on Thursday.

Of similar vintage is the China-ASEAN Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) that was signed in 2002 and was meant to pave the way for the COC. But analysts say a final deal is still a long way off.

At the ASEAN virtual summit this week, where the bloc agreed to establish a "comprehensive strategic partnership" with Beijing, Chinese Prime Minister Li Keqiang urged ASEAN countries to "expedite COC (Code of Conduct) negotiations and strive for its early conclusion." Chinese officials have been reportedly pressing for a conclusion by the end of next year.

ASEAN members Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam contest parts of the South China Sea with China, which claims 90 percent of the area. Over the past decade, it’s become an issue that has divided the Southeast Asian bloc, because of the competing interests of its members – including non-claimants like Cambodia with close ties to Beijing.

“As the 2022 ASEAN Chair, Cambodia will play a vital role in the negotiation process to finalize the Code of Conduct for the South China Sea,” said Kimkong Heng, a PhD candidate at the University of Queensland and visiting senior research fellow at the Cambodia Development Center.

But Viet Hoang, a well-known Vietnamese commentator on South China Sea, told RFA this week that given ASEAN’s consensus-based decision-making, “I can’t see how ASEAN countries and China can achieve any agreement on key issues, even if China’s ally Cambodia will take over the bloc’s presidency next year.”

Risk upsetting China

In his speech at the closing ceremony of the ASEAN summit on Thursday, Hun Sen said Cambodia “will steer ASEAN’s collective efforts to accomplish our most important tasks – especially expediting the rebuilding process of an equitable, strong and inclusive ASEAN Community.”

According to Heng, this will be a crucial year for Phnom Penh "to improve its international image which was damaged in 2012 when it was accused of siding with China and preventing ASEAN from reaching an agreement" on the South China Sea.

It was the first time in the bloc’s 45-year history that ASEAN failed to issue a joint statement.

Again in 2016, after the Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration awarded the Philippines a legal victory against China's maritime claims, ASEAN foreign ministers also failed to issue a joint communique due to Cambodia's objection to the mention of the South China Sea dispute.

“However, the opportunity and ability to mediate the South China Sea disputes will be constrained by Cambodia's close relations with China,” said the Cambodian researcher, adding: “Given China's growing influence and presence in Cambodia in many areas, including economy and military, it's unlikely Cambodia will do something to upset China.”

Hun Sen in his summit remarks reiterated what he called “the core spirit of ASEAN” - “One Vision, One Identity and One Community.”

ASEAN since its establishment in 1967 has been operating based on consensus, yet according to Carl Thayer, emeritus professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia and a long-time Southeast Asia watcher, “many years ago ASEAN gave up its prerogative to reach a common position on the Code of Conduct prior to meeting with China.”

Claimants like the Philippines, Malaysia and Vietnam don’t share the same interests as non-claimants such as Laos and Cambodia.

Since 2013, however, ASEAN has come up with a formulation on the South China Sea that is included in every chair’s statement, he said, that means Cambodia cannot refuse to issue the chair’s statement because of wording of paragraphs on the South China Sea.

Thayer pointed to the well-worn statement that is repeated every year and seen in both ASEAN chair’s statement of the 38th and 39th ASEAN summits in 2020 and 2021.

“We… were encouraged by the progress of the substantive negotiations towards the early conclusion of an effective and substantive Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC) consistent with international law, including the 1982 UNCLOS, within a mutually agreed timeline.” UNCLOS is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Furthermore, ASEAN chair or not, Cambodia is only one of the parties to the COC negotiations between ASEAN and China, hence “has no special authority to influence the timeline,” added Thayer.

That puts Phnom Penh in a tricky position with very little room to maneuver, according to Kimkong Heng.

“Cambodia will likely continue to assert that the claimant states should address the disputes bilaterally and stay away from getting involved in this hot issue,” he said.

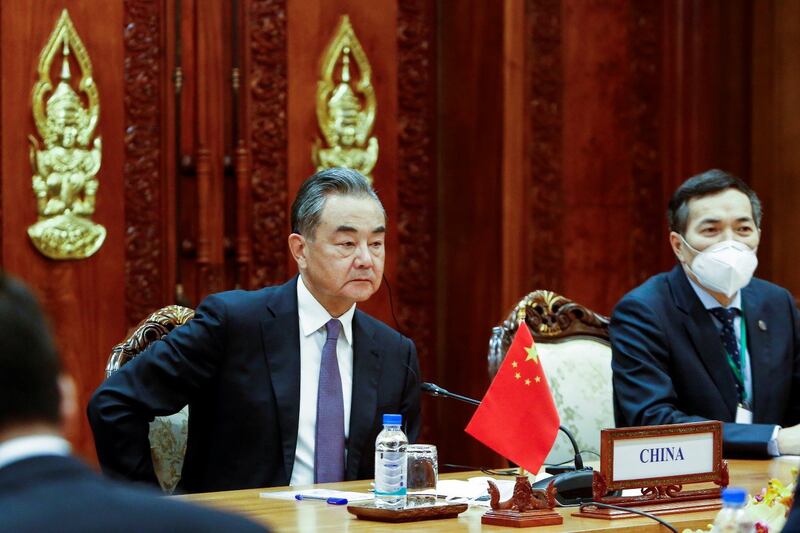

In recent years, Cambodia has become "China's iron-clad friend and friendly neighbour," as described the Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi.

China accounts for about 90 percent of foreign direct investment in Cambodia and Phnom Penh has become even more dependent on Beijing after the U.S. and E.U. imposed various sanctions on the Southeast Asian state.

"If I don't rely on China, who will I rely on?" Hun Sen famously said at an international conference in May this year.

The South China Sea COC negotiation process is likely to get even more complicated since China accused some non-regional players, especially the United States, of getting involved.

The U.S. says its activities in the South China Sea are aimed at ensuring a free and open Indo-Pacific but Beijing says they're designed to counter China's influence. Washington also alleged that China had established a military presence at the Ream Naval base in southwest Cambodia.