Members of Cambodia’s Candlelight Party marked the anniversary of a deadly grenade attack on an opposition rally Wednesday with demands for justice in the case that remains unsolved despite a 25-year “investigation” by authorities.

Around 200 party officials and family members gathered at a stupa in the capital Phnom Penh where they held a Buddhist ceremony dedicated to the 16 victims of the March 30, 1997, attack on the rally led by Sam Rainsy, the acting president of the dissolved Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) who now lives in exile to avoid what are widely viewed as politically motivated charges and convictions.

In an interview with RFA’s Khmer Service, former CNRP Sen. Ly Neary, the 79-year-old mother of one of those who died in the attack, expressed her frustration over the failure of authorities to bring her son’s killers to justice.

"It's been 25 years, and authorities have yet to conclude their investigation," she said. "I don't have any hope for a resolution."

Nonetheless, Ly Neary urged the government to keep the case open and hold those responsible to account.

She said her son, a doctor, had been proud to take part in the rally at Phnom Penh’s Wat Botum Park, where protesters gathered across from the National Assembly to denounce the judiciary’s corruption and lack of independence.

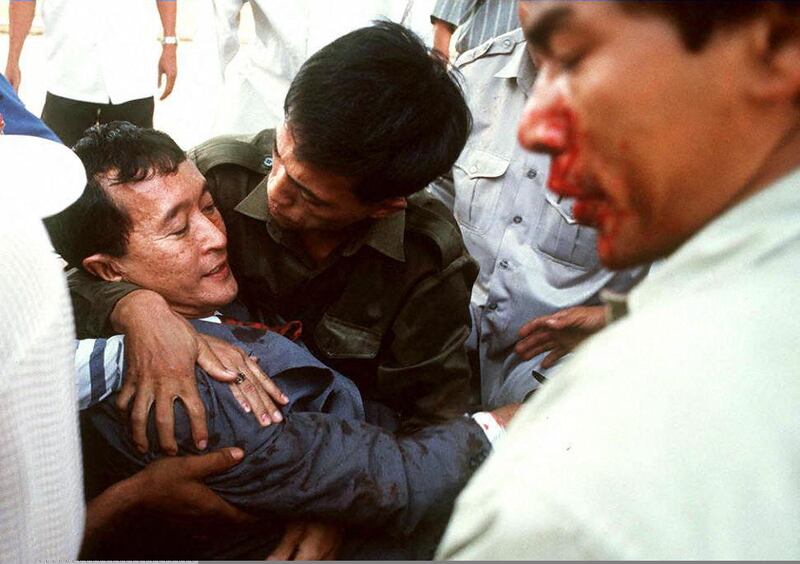

While Sam Rainsy is thought to have been the target of the attack, the assailants missed him, killing his bodyguard, as well as some protesters and bystanders. The blasts blew the limbs off nearby street vendors and left more than 150 people injured.

According to eyewitness accounts, the people who threw the grenades ran toward Prime Minister Hun Sen’s riot-gear clad bodyguards, who allowed them to escape.

An FBI report declassified in 2009 indicated that Cambodian police possessed prior knowledge of the attack and that there was the possibility that the attackers colluded with Hun Sen’s bodyguard unit.

Despite the toll of death and dismemberment, no one has been arrested for the attack, leaving victims and family members still searching for justice.

‘Investigation’ continues

Government spokesman Phay Siphan told RFA that the case remains open and urged family members to submit any new evidence they find to authorities for further investigation.

He criticized the Candlelight Party for exploiting Wednesday’s ceremony “to draw attention for political benefit.”

“The court continues to accept complaints and information from the public and organizations to find those responsible for the grenade attack,” he said.

RFA was unable to reach National Police Spokesman Chhay Kim Khoeun for comment on the status of the investigation on Wednesday.

Hing Bun Heang, the commander of Hun Sen’s Bodyguard Unit, denied involvement in the grenade attack in an interview with RFA and dared anyone to present evidence to the contrary.

“I already clarified this [with the FBI]. I wasn’t involved. I don’t know anything,” he said.

“Show me a photo of me throwing the grenade,” he added, threatening to “use a machine gun against anyone who accuses me.”

Hing Bun Heang was sanctioned by the U.S. government in June 2018 over his unit’s alleged role in the grenade attack, as well as several other assaults on unarmed Cambodians.

Kata Orn, spokesman for the government’s Cambodia Human Rights Committee, told RFA that officials have been working with the FBI to apprehend the suspects in the case.

He also dismissed a French judge’s order last month that Hing Bun Heang and another security aide for Hun Sen named Huy Piseth be tried for organizing the attack.

“Cambodia has a constitution to protect Cambodians,” he said, adding that the French court would never be able to enforce its verdict against the two generals outside of its jurisdiction.

In an interview with RFA last month, Brad Adams, Asia director of New York-based Human Rights Watch, said a conviction in the French court could lead to enhanced sanctions against the two individuals and an Interpol Red Notice, or a so-called European arrest warrant, in their names.

‘No light’ of accountability

Former Sen. Ly Neary said that while she welcomes the French court order, authorities in Cambodia should be responsible for pursuing the case. She questioned why the onus is on the families of the victims to pursue justice for their loved ones.

“I am a regular citizen. How can I ‘find evidence?’ Only the authorities have the legal right to do so — regular citizens can’t do it,” she said.

Candlelight Party Vice President Thach Setha called Phay Siphan’s comments “disrespectful” to the victims and their family members.

“[The government] can’t find the suspects, so instead they accused us of exploiting the event,” he said.

Ny Sokha, president of the Cambodian rights group Adhoc, told RFA that if the government really had any interest in seeking justice for the victims, the French court warrant would be “a good start.”

“The government doesn’t have the will to seek justice [for the victim] because it has already been 25 years,” he said.

“There is no light [to hold the perpetrators accountable]. This is yet another example of [official] impunity.”

Translated by Samean Yun. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.