A pair of dodgy investment schemes link an Australian businessman to the upper echelons of the Cambodian People’s Party.

The daughters of one of Cambodia’s most notorious and long-serving generals acted as fronts for an Australian real estate fraud valued at roughly $100 million, according to a 2019 federal court order.

Gen. Pol Saroeun is one of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen’s most trusted lieutenants – commander-in-chief of the armed forces from 2009 to 2018 and now a senior minister.

RFA has identified wealth and assets enjoyed by Saroeun’s family across three continents, as part of an ongoing investigation into money and property that politically connected Cambodians have squirreled away overseas.

In Australia, the Saroeun family was involved in a ‘land bank’. These are controversial investment vehicles that divide large tracts of undeveloped land into smaller parcels to be bought up by investors in the hope that one day planning permission will be granted for residential development, sending the value of the land skyward. The Australian government cautions that many investors lose their money to such schemes that are managed poorly, or even fraudulently.

Saroeun’s daughters Pol Pisey and Pol Sotheavy were embroiled in a scheme that was fraudulent. In July 2011, they were granted, for a nominal sum, five million shares in Aviation 3030 Pty Ltd, an Australian company established as a land bank. Last year, a federal judge ruled to shut down the scheme in response to a case brought by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission.

Frontwomen for fraud

Aviation 3030’s founder is Hakly Lao, an Australian Khmer identified as having connections at the highest levels of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, including with at least one of Hun Sen’s children.

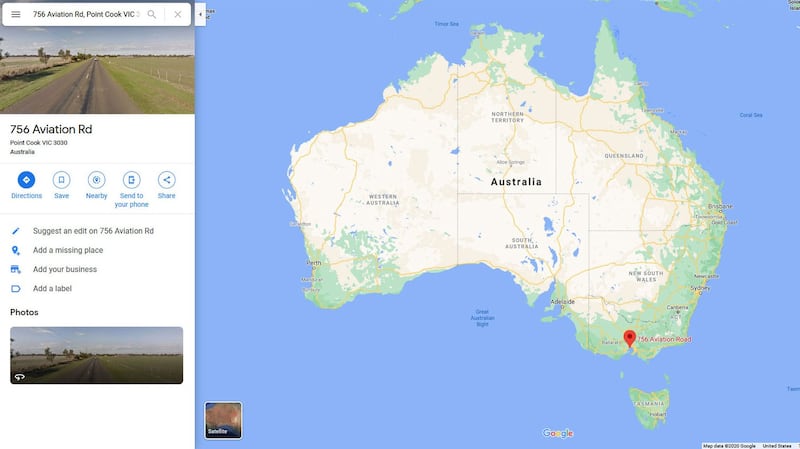

Lao established the company in 2011 after identifying a 240 acre patch of land in the Melbourne suburb of Point Cook that it purchased for 7.8 million Australian dollars (US$5.6 million) in May of that year.

Two months later, the Pol sisters bought their five million shares, representing five acres of land, for a total of 50 Australian dollars (US$36). An equivalent allotment of shares would subsequently cost retail investors up to one million Australian dollars (US$715,000) – a 1,999,900 percent mark-up on what the sisters paid.

In finding against Aviation 3030 in March 2019, Justice John O’Callaghan described Pol Pisey and Sotheavy as “nominees” for the company’s founder, Lao. The general’s daughters had seemingly allowed their names to be used to obscure Lao’s beneficial ownership of the shares from future investors.

It is not clear what benefit the sisters derived from the arrangement. But it was only the beginning of a series of smoke-and-mirrors techniques deployed by Lao to dupe his investors.

Three days before Pisey and Sotheavy were brought on board as nominee shareholders, Lao had already set in motion a pattern of self-dealing that would continue until Aviation was taken off his hands by the court nearly 10 years later.

On July 15, 2011, AuDirect Property Group Pty Ltd, an Australian company beneficially owned and directed by Lao, entered into an agreement with Aviation 3030 that would see the land bank paying it millions of dollars in management fees.

In registering the similarly named AU Direct Group Co Ltd in Cambodia, Lao gave as his home and the company’s headquarters addresses also used in corporate registrations by Sotheavy and her husband Khiev Sokha. The Cambodian AU Direct is no longer listed with the Ministry of Commerce and records archived by U.K. investigations and advocacy group Global Witness offered no indication of the company’s purpose.

It is unclear how or when the Pol and Lao families first became acquainted – members of neither family responded to requests for comment for this story. Explaining his decision to wind up Aviation 3030 and place the company in the care of administrators, Justice O’Callaghan gave a laundry list of grifting by Lao and his fellow directors.

“Directors have issued to themselves and to their associates large numbers of shares at a gross undervalue; they have fabricated correspondence and invoices; they have provided false instructions to the company’s external solicitors; they duped and misled investors; they entered into related party loans; and they made unauthorised and exorbitant expenditures,” O’Callaghan wrote.

Decades of deception

The Pol sisters were not the first members of Cambodia’s political elite to find themselves embroiled in Lao’s illegal business practices.

In 2018, a year prior to Aviation 3030 being shut down, a similar Melbourne land banking scheme chaired by Lao was ordered wound up for failure to properly register with the authorities. The scheme, known as the VKK Investments Unit Trust, had raised 22 million Australian dollars (US$15.7 million) from investors.

According to court records first reported on by Al Jazeera in 2018, among those investors was Kong Vibol, head of Cambodia’s tax department. In 2012, Kong filed a lawsuit against his fellow investors in VKK, as well as the scheme’s operator, Gem Management Group, which was owned and run by Lao.

Amid allegations that the tax chief had deployed “threats and intimidation” against the defendants, lawyers acting for Kong were seeking a summary judgement of 4.1 million Australian dollars (US$2.9 million) in damages. Their application was denied 2014 and the case does not appear to have resurfaced in court since.

In recent years, Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) has made a concerted effort to engage the diaspora community in Australia. In a speech to the Australian House of Representatives, parliamentarian Julian Hill said those efforts have included alleged involvement in serious crimes such as money laundering, intimidation and smuggling of heroin, cigarettes and alcohol.

Outreach has also taken less sinister forms, such as the organizing of community groups and events. Formerly a CPP member, whistleblower Kalyan Ky was actively involved in those efforts in Melbourne.

In 2014, Ky says she was invited to a meeting at a restaurant in the Melbourne suburb of Burwood by Hun Manith, director of Cambodian military intelligence and son of Hun Sen. In her recollection, there were approximately seven individuals gathered around the table, including Hakly Lao.

“He was at all the major events and also the first meeting we had with Hun Manith. They seem pretty close,” Ky told RFA. “He was more connected with the higher-ups than the ordinary members.”

The business interests of Gen. Pol Saroeun’s family stretch from Cambodia, to Australia to the United States, RFA reporting shows. The accumulation of wealth across continents is a far cry from where the patriarch began his career -- as a cadre of the Khmer Rouge.

He joined the revolutionary group in 1968, aged 20, and spent the next decade working for the eradication of private property, often through violent and inhumane means.

According to a 2018 report by Human Rights Watch, between 1975 and 1978, Saroeun oversaw S-79, a Khmer Rouge prison, “where members of the East Zone military accused of betraying the revolution were detained without charge or trial, often tortured during interrogation, and then arbitrarily either executed or held for ‘re-education.’ Re-education took place at a workplace run by Pol Saroeun.”

If Saroeun’s family fortunes are anything to go by, he has since abandoned the Khmer Rouge’s ideological disdain for private wealth.

His wife, Noup Sidara, owns and manages a string of businesses across Cambodia. Those include several mines and quarries, many of which civil society organisations accuse of operating illegally and under the protection of military units commanded by Saroeun.

His daughters also hold shares in and sit on the board of several Cambodian companies. Sotheavy was co-owner and director of an Australian company, Khamvuth Kingdom, until it was de-registered last year. The company’s purpose, if it had any, is unclear and its Cambodian-born co-owner was not reachable for comment.

Sotheavy and her husband, Sokha Khiev, also have a retail business in the U.S. state of Texas, where she owns a home valued at approximately US$200,000.

In the March 2019 ruling on the Australian land banking scheme, Justice O’Callaghan conceded that the Australian Securities and Investment Commission was taking an unusual step in asking him to wind up a company in which investors “stand to make significant profits.” A shadowy Chinese property developer, Dahua, has offered to purchase the plot of land for roughly 135 million Australian dollars (US$96.4 million), almost 20 times what Aviation 3030 originally paid for it.

However, O’Callaghan found that the regulator had made an “overwhelming” case that there is a public interest in the company’s winding up, thanks to the “the many and varied ways that the directors have demonstrated that they are unfit to sit on the board of Aviation [3030].”

Despite the judge also finding that the Pol sisters were acting as nominees for Lao, they still retain their five million shares in Aviation 3030. If the Dahua sale goes through, Sotheavy and Pisey could stand to net between two and three million Australian dollars (US$1.4 million and US$ 2.1 million) out of the deal.