In 2019, Sak Mom was scrolling on Facebook when he saw ads for a gated community, or borey, on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. Houses at Borey VIP were selling for about $50,000 each, and it seemed like an ideal place for the newly married couple to start a family.

“We thought we had the money,” Mom, 29, told Radio Free Asia last month. He and his wife sold custom children’s dolls for up to $150 each — sometimes four or five daily — and detailed motorbikes on the side. “We believed we could own our own home.”

The developer, R.N. VIP Real Estate, promised Mom’s unit would be done in 18 months, so he and his wife rented an apartment nearby. But 18 months stretched into four years, during which time the developer demanded Mom pay off the entire house even as construction on the project stalled, Mom said.

Cambodia’s real estate market has experienced a sharp decline in recent years and boreys like these have become the epicenter of the country’s bubbling housing crisis.

Cash-strapped developers are struggling to complete projects without upfront payments, and have resorted to using buyers' land titles as collateral for loans. Lower- and middle-class customers, crushed by pre-existing debt and pandemic-induced unemployment, are falling behind in payments the developers desperately need to finish building.

The result is delayed or abandoned boreys or units that deliver at a fraction of the promised quality and buyers being locked out of their homes. Disputes have sometimes turned into violent protests, which have caught the attention of the government during a key transition period when new Prime Minister Hun Manet seeks to stabilize and grow the Cambodian economy.

The borey crisis embodies Cambodia’s uneven recovery from Covid-19, with the once-flush construction and real estate industries casting a pall over the economy even as sectors such as tourism and hospitality rebound. For middle-income families who were encouraged to purchase homes, the impact has been devastating.

In Mom’s case, living about 40 minutes away from his customer base in the capital — combined with Cambodia’s overall economic downturn — has hurt business. He now sells just one doll every few days and worries about keeping up with his loan repayments. Other borey residents, which include young families like Mom’s and older people who moved from other provinces to purchase property, said they were concerned about safety in the half-empty development.

“First you hear other boreys have problems,” Mom said. “But then it was our borey, too.”

‘Real estate mad’

Fueled by foreign cash, the dollarized economy, and a pay-to-play regulatory environment, Phnom Penh’s villa and condo market took off in the mid 2000s. The borey — a development of attached or unattached homes reminiscent of an American suburb — emerged as the market’s counterpart for lower- and middle-class Cambodians.

For those ascending the economic ladder, boreys offered space and affordability. They also offered the land beneath the unit: a potent symbol in a country where private land ownership was abolished during the Khmer Rouge genocide.

The properties gained particular traction shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic, when the effects of foreign direct investment and a strong tourism sector had given many families more purchasing power, according to Kinkesa Kim, Cambodia country director at the brokerage firm CBRE Cambodia.

“All of this activity injected money into local consumers’ pockets. They had cash that they didn’t need, or they wanted to expand or upgrade their homes,” Kim told RFA. “A lot of people relocated from the center of the city to the secondary or suburban districts.”

Between 2019 and 2022, the supply of borey units roughly doubled from about 60,000 to 120,000, data from CBRE show.

But the boom wouldn’t last. One real estate executive, who asked for anonymity to speak critically, told RFA that the sudden growth mirrored the prelude to the global 2008 financial crisis, spawning oversupply and risky financing as “everyone went real estate mad.”

Inexperienced developers rushed into the game, offering in-house loans that bypassed banks — but with 12 or 13 percent interest rates. Meanwhile, several little-known tycoons, who have since been accused of fraud and arrested, marketed Ponzi schemes as borey or land plot projects.

“A lot of developers are idiots. They’ve never done a project before, they don’t hire good people, they think they’re good at interior design, they think they’re good at space planning — and they don’t want to spend any money to figure all that stuff out,” the executive said. “Like, I’d never go to the dermatologist and say, ‘Get out of the way, let me take over.’”

The Covid-19 pandemic pricked the balloon. More than 200 garment factories — the country’s biggest formal employer — closed amid a mass lack of overseas orders, putting tens of thousands of people out of work. The international tourism industry collapsed, while repeated lockdowns cut domestic spending. As the pandemic exposed Cambodia’s structural weaknesses, the real estate sector stalled out.

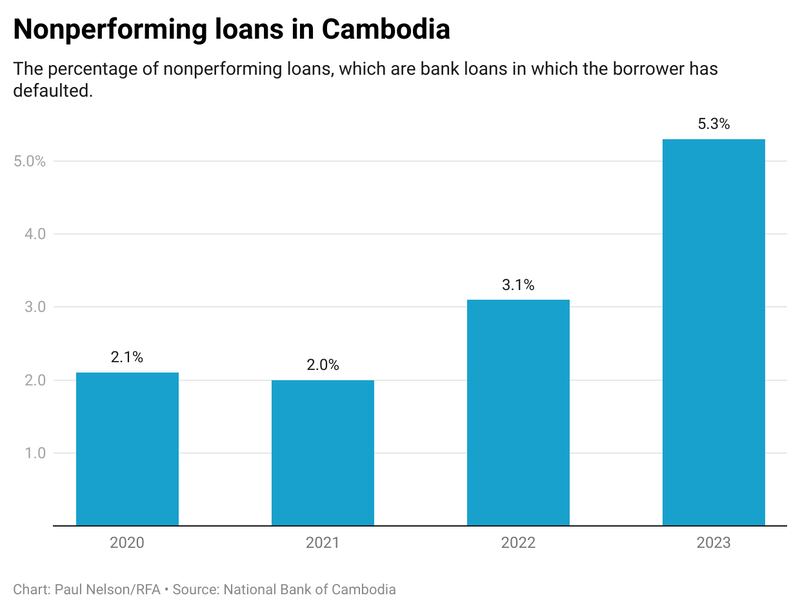

By the end of 2022, nonperforming loans had risen to 3.1%, compared to about 2% at the end of 2021, according to data from the National Bank of Cambodia. The World Bank called for close monitoring of “elevated credit growth, high levels of private debt, rising nonperformance loans, and the concentration of related risks in the construction and real estate sectors to ensure macrofinancial stability.”

Just over 60 borey projects were launched that year, per CBRE, compared to a peak of more than 100 projects the year before. By 2023, the number had dropped to fewer than 20 projects.

Boreys were a uniquely vulnerable slice of the real estate sector because they were supply-driven and targeted people whose financial positions were more precarious, said Sylvia Nam, a former University of California, Irvine professor who has extensively researched Cambodia’s urban development.

“Its proposed benefits are also the force of its weakness,” Nam told RFA. “The borey market was supposed to satisfy the needs of local Cambodians in a way that was always more of an aspirational sales point than a viable market opportunity.”

‘It’s like they borrowed money from the poor’

As the borey market cooled, it wasn’t just new developers who struggled.

On Facebook, tycoon and real estate developer Leng Navatra’s page is filled with photos of busy construction workers and smiling owners at Borey Leng Navatra 6A, his affordable housing project in Kandal province.

But the page is also speckled with comments from buyers publicly begging the tycoon to finish their long-delayed homes.

One buyer, Ram Somrong, told RFA he paid $18,800 for a house four years ago, with his contract stating he would receive the keys after 18 months. But his unit still doesn’t have a finished foundation or walls. “The company claims it’s in economic crisis,” Somrong told RFA. “The impact is that we need to spend [money] to rent a house — but we also took money from the bank to pay for the borey.”

Located near National Road 6 north of Phnom Penh, the sprawling construction site rises out of a landscape more rural than urban, where shells of other abandoned boreys dot the roadside. Workers live in tightly packed metal shacks on the edge of the property.

Three construction managers, who asked for anonymity for safety reasons, said payments from the developer are frequently late for weeks or months at a time, causing the workers — most of whom are indebted with microfinance loans — to refuse to take on overtime. One manager told RFA he, too, relies on loans to pay workers out of his own pocket.

“It’s like they borrowed money from the poor to start their business,” the manager said. “At this point, we don’t know why they’re slow to pay. The tycoon has a lot of money — so why?”

Navatra is a young but well-connected oknha — an honorific given to those who have donated at least $500,000 to the government — who also runs a music label. He has reassured buyers that he will finish their units. Neither Navatra nor his company could be reached for comment, but in a July Facebook post, he wrote that the company was handing over keys to buyers and apologized for delays.

Falling behind

Other borey conflicts have escalated beyond online frustration to physical protests.

At Borey Piphup Thmey Kamboul III, west of the Phnom Penh International Airport, financially downtrodden buyers are in a stalemate with a well-established developer they claim violated their contracts.

Starting around 2022, hundreds of Kamboul buyers who had been paying off their properties for years fell behind in payments. Rather than buying back homes for 50% of the purchase price, as promised in their contracts, developer Borey Piphup Thmey simply locked people out — prompting months of protests and government petitions.

During a recent visit by RFA, the borey was quiet with rows of finished houses padlocked and abandoned, some plastered with signs warning about missed tax payments.

“People left with nothing,” one current resident, who repurchased a home that had been confiscated from another buyer, told RFA. “Without paying money on time, they will take away the house.”

The resident, who works as a civil servant and requested anonymity for safety reasons, said he can pay the $400 monthly installments on his $50,000 unit only with help from his adult children. Households with just one or two incomes received the brunt of confiscations, he said, when factory jobs and other work dried up.

“Even me, I’m late to pay, but I never fail to pay,” the resident said. “During the Covid-19 pandemic, we thought that it was very difficult — but this period is more difficult.”

RELATED STORIES

[ Sign says Phnom Penh land dispute is settled – but residents disagreeOpens in new window ]

[ New Cambodian policies aimed at foreign real estate investmentOpens in new window ]

[ Cambodia’s economy is running out of steamOpens in new window ]

Tycoon Hong Piv, owner of Borey Piphup Thmey, said last November he had attempted to resolve the dispute with residents multiple times and has spent at least $5.6 million buying back more than 450 homes. Hong Piv could not be reached for comment.

Property markets across Southeast Asia have seen a mixed recovery from Covid-19, but Cambodia has struggled in particular because of its oversupply and reliance on Chinese investment, which dropped off amid China’s own real estate slowdown.

It’s not clear when the industry will bounce back. In a report last month, financial insights company S&P Global warned that Cambodia’s “risk-return perspective is weaker” compared to peers, with the real estate sector’s downturn likely to continue. Nonperforming loans, the report added, are predicted to rise for two more years until peaking around 7.7% in 2026.

Government solutions

The Cambodian government regularly prosecutes victims of land disputes, from jailing women who have fought the development of Phnom Penh’s last lake, to filing charges against residents who have tried to petition against sugar barons, to doling out years-long prison sentences to indigenous people documenting officials destroying their property.

But the borey conflicts — dominated by people with marginally more money and political power — have garnered a more conciliatory response.

Last year, the Ministry of Economy and Finance deferred taxes for borey developers and encouraged loan restructuring, while the Real Estate Business and Pawnshop Regulator has issued periodic warnings about investing in unlicensed borey projects.

In June 2023, then-prime minister Hun Sen called upon developers to stop confiscating homes and instead rejigger payment plans, saying that “any house seizure is not good for the national economy and society.”

More recently, after an April protest that saw Piphup Thmey residents burn tires in the streets, Prime Minister Hun Manet promised that his government was searching for solutions for the borey crises.

Hun Manet, who has a PhD in economics, has named economic growth as a priority, with the goal of making Cambodia an upper-middle-income country by 2030.

“I would like to emphasize that the Royal Government is aware of the problem,” he said. “We see and understand the hardships experienced by the people.”

But the broader picture remains grim. Nonperforming loans rose from 2022 to 2023, and Cambodia has the fifth highest ratio of private debt to GDP in the world, trailing Hong Kong, the U.S., China, and Japan, according to the World Bank.

The first half of 2024 saw the fewest borey launches in a decade: two.

Some families are in too deep to consider alternatives. Sak Mom, the father of the one-year-old at Borey VIP, has paid off two years of his seven-year loan. When asked if he would choose to live in Borey VIP all over again, he laughed.

“We have no choice,” he said.

Additional reporting by RFA Khmer. Edited by Abby Seiff and Boer Deng.