On a stifling July afternoon, hundreds of Cambodian officials gathered in central Phnom Penh to extol the importance of forests. Saplings, 40,000 in total, were given away for planting. Nationwide, hundreds of thousands more are expected to be distributed in the coming months.

In all, the plan is for 1 million trees to be planted this year alone with the aim of increasing Cambodia’s forest cover by 60% by the end of the decade, Minister of Environment Eang Sophalleth said in a speech to mark the Arbor Day event on July 10.

“A tree is like an oxygen tank. It gives us air to breathe and helps us stay healthy,” said Eang Sophalleth. “The tree has also helped to make profit in Cambodia. Planting trees is like an investment for the younger generation.”

Profit and trees have long gone hand in hand in Cambodia.

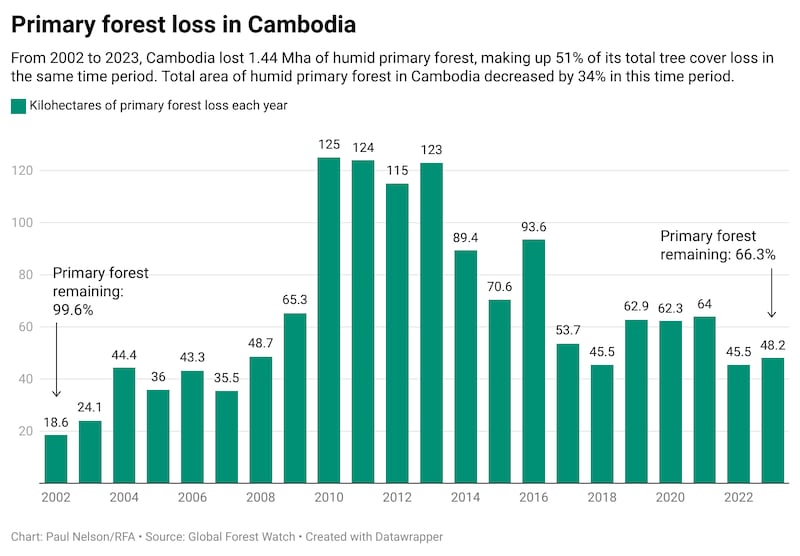

In 2023 alone, Cambodia lost 114,000 hectares of natural forest – equivalent to an area the size of Los Angeles – according to Global Forest Watch, an open-source data mapper. From 2001 to 2023, the country lost more than half of its total tree cover.

A significant amount of that loss comes from Economic Land Concessions, or ELCs. These are often large tracts of state forest that the government sells or leases to developers, who then usually log valuable timber and convert the land into industrial plantations for crops like cashew, rubber and soybean sugar.

Environmentalists and human rights activists have long decried these concessions, which have rapidly destroyed forests and are frequently reported to stretch beyond their boundaries. Often, such concessions are accompanied by illegal logging that further degrades protected areas.

Instead of working with outspoken environmentalists to safeguard protected areas, the government has frequently clamped down on perceived critics. Just days before the Arbor Day event, ten activists with the environmental group Mother Nature were given unprecedented prison terms.

Rather than addressing the mounting threats to Cambodia’s dwindling still-standing forests, the government is doubling down on a reforestation strategy research has proven rarely survives in the long term.

“We have to be really careful about not trading off these precious old-growth forests with newly planted areas because those new areas are not a certainty,” said Lindsay Banin, a statistical ecologist with the U.K. Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. “They may not survive. They may not grow well. They may not have that same diversity and complexity that these old growth forests have.”

The great tree giveaway

Globally, tree plantings are a mainstay in government and private sector responses to climate change and deforestation. The number of organizations attempting tree planting has risen by nearly 290% in the past three decades, according to a 2021 study published in Biological Conservation.

This trend is also true in Cambodia.

In 2022, the government spearheaded a highly-publicized and rapid reforestation effort in Phnom Tamao Forest, just 40 kilometers from Phnom Penh. The protected area had been partially cleared to make way for a satellite city near the Kingdom’s planned new airport. The clearance drew such extreme criticism that then-Prime Minister Hun Sen personally responded with a rare backtracking, canceling the project and ordering the reforestation. Regional reforestation experts, however, expressed major concerns over the tactics used, which they believed were more political than scientific.

Even when taking into account these one-time tree planting efforts in specific forests, like Phnom Tamao, nothing compares to the purported scale of Cambodia’s new 1 million trees campaign.

At the opening day of the Ministry of Environment’s “Green Sprouts” tree sapling exhibition in Phnom Penh, Deputy Prime Minister Hun Many and First Lady Pich Chanmony toured booths displaying saplings, seeds, succulents and potted plants.

While the opening event was closed to the broader public, neckerchief-wearing scouts and camouflaged wildlife photographers competed for Pich Chanmony’s attention while grinning Red Cross volunteers and provincial department officials vied to show Hun Many the tree plantings they had funded or saplings they had raised.

Tree planting, Hun Many said in his speech, will “change the mindset” of the Cambodian people to “love trees.” He emphasized the campaign has the full support of his older brother, Prime Minister Hun Manet, who succeeded their father, Hun Sen, after the national elections a year ago this month.

“Trees are the most essential asset of the ecology system and play a very important role for the economy and the environment,” said Hun Many, adding that planting trees will mitigate natural disasters, combat climate change and attract more tourists.

Eang Sophalleth has been drumming up support for the reforestation initiative since last year, with some details trickling out over the course of a few public speeches and press briefings.

At a climate change summit in November, Eang Sophalleth stressed that “only reforestation can save the planet from being burned by the increasing temperature.”

All 25 provincial environmental departments would begin distributing 100,000 saplings annually, until at least 2030 with the aim of getting back 60% of forest cover. To track the reforestation, a new social media-like app would be developed by the Ministry of Environment for members of the public to upload information about their planted trees. The app has yet to launch, though it has been named Chakra.

“I don’t want to put the burden on the government to spend millions of dollars to do reforestations,” said Eang Sophalleth during his speech. “Let’s give the trees free to the population to plant it, to take care of it.”

While the Ministry of Environment signed off on the plans for the development of five new seedling nurseries, there is little concrete direction or explicit instruction — other than to give people saplings and ask them to download the forthcoming app in order to post about planting it. Designated reforestation plots have not been announced, nor has the full list of species being distributed been made accessible.

Popular plan, poor track record

Studies have found an exceedingly low survivability rate among reforestations in the region.

Banin, at the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology, examined more than 170 reforestation sites in Southeast Asia and in a collaborative 2022 study found that nearly a fifth of planted trees die within the first year. This mortality rate rose to almost half of the trees dead in a decade.

“A new sapling is not equivalent to a big old-growth tree,” said Banin, explaining that old trees often create a diverse ecosystem around them over time, capture carbon at much higher rates and provide seeds for the next generation of trees.

Forest defenders

The big bet on tree planting comes in lockstep with long-term, simmering forest issues across the Kingdom, exemplified by the sentencing of the Mother Nature activists.

“Environmental destruction is blatant for everyone to see,” said Alejandro Gonzalez-Davidson, who founded Mother Nature Cambodia and who was sentenced in absentia to eight years in prison at the same trial. “Cambodia has seen, over the last three to four decades, a massive erosion, if not outright destruction of the environment – logging is of course the main one.”

He called the tree planting campaign “laughable.”

“Why do I say this is laughable? Well, because the first thing that comes to people’s mind is, what about the forests that are still standing? These are not being protected. These continue to be privatized under different schemes,” Gonzalez-Davidson said. “Why on Earth are we concentrating so much on replanting? We are not protecting what is standing.”

As officials in Phnom Penh extolled their million-tree initiative, Cambodians defending their forests hundreds of miles away wondered what such efforts had to do with their work.

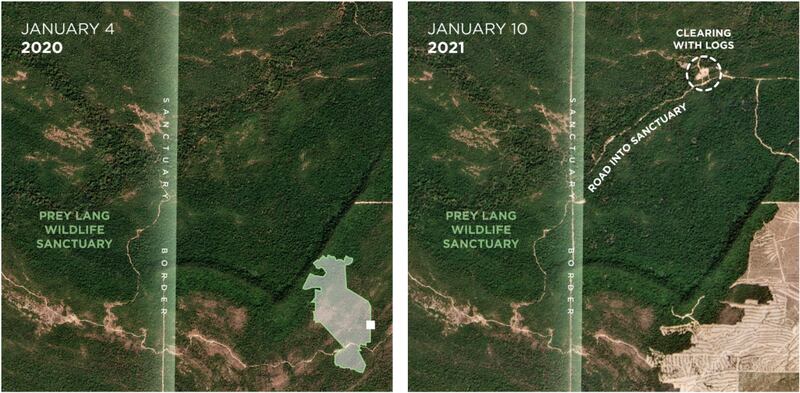

Spanning the borders of four provinces, Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary sprawls across more than 430,000-hectares of once-dense forest. Though classified as a protected area, the sanctuary has seen some of the highest levels of deforestation in the country.

Cashew farms and other cash crop plantations, some of them granted through ELCs, encroach on the borders of Prey Lang’s western most quarter in Kampong Thom Province. Elsewhere deep inside the forest, illegal logging has toppled massive old growth trees for steep profits.

Toch Khin, a member of the Prey Lang Community Network, has long been a part of the efforts to document deforestation within the sanctuary.

In late July, sporadic rain showers drenched Toch Khin as he patrolled the forest in an attempt to deter activities, like illegal logging and poaching, a relatively risky task that can often be at odds with local police and Ministry of Environment rangers.

Asked about the ministry’s tree planting effort, Toch Khin looked genuinely surprised.

“I have never heard of it, and I have never seen the ministry plant trees anywhere in Prey Lang,” Toch Khin said. “Here, trees are usually taken out. Not put in.”

Edited by Abby Seiff and Boer Deng.