The family of former Prime Minister Hun Sen is solidifying its already iron grip on Cambodia after the National Assembly on Wednesday voted unanimously to appoint Minister of Civil Service Hun Many as a deputy prime minister.

Hun Many, 41, is the youngest son of Hun Sen, who stepped down as prime minister after last year’s national elections in favor of eldest son Hun Manet, 45.

He received all of the 120 votes during an extraordinary session of the Assembly and is now one of 11 deputy prime ministers, local media reported.

The promotion of Hun Many was in line with the need to achieve the “highest efficiency of the government’s policy” as the government seeks to turn Cambodia into a high-income country by 2050, Prime Minister Hun Manet told lawmakers, according to Agence France-Presse.

The appointment was not unexpected. On Feb. 16, exiled opposition leader Sam Rainsy said Hun Many's new position would show that "this regime is a feudal clan, as far away from public accountability as any in the world."

Instead of working to resolve major national issues, Hun Manet is apparently focusing on strengthening his family’s influence, said In Nath, the president of the Cambodia Alliance for Paris Peace Accords, an organization that seeks to educate Cambodians about democracy.

“Dictators have always appointed their family members and close relatives to consolidate power,” he said.

Thaksin and Hun Sen

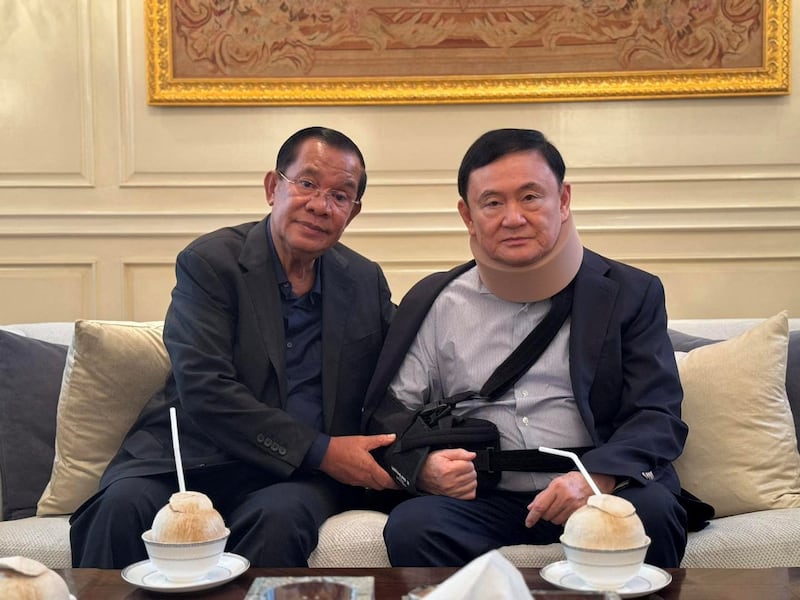

Also on Wednesday, Hun Sen traveled to Bangkok on a private plane to visit Thaksin Shinawatra at the former Thai prime minister’s residence.

Hun Sen, 71, was pictured sitting next to Thaksin, who wore a neck brace and had his right arm in a sling, as they enjoyed coconut drinks in the living room, according to BenarNews, an RFA-affiliated online news service.

“Despite Thaksin being ill, he gave a warm welcome as if we were siblings, with Paetongtarn, his youngest daughter and leader of the Pheu Thai Party, also present. I have invited Paetongtarn to visit Cambodia on March 14-15,” Hun Sen said in a post on his Facebook page.

Thaksin was released from the Police General Hospital on Sunday, after being held there due to ill health for six months on corruption charges following his return from exile. He served as Thai prime minister from 2001 to 2006.

Hun Sen provided Thaksin with sanctuary during his subsequent 15-year exile, allowing him to visit frequently as a special adviser to Cambodia.

Thaksin’s Pheu Thai party returned to power in September at the head of a new coalition government.

During Hun Sen’s visit, the area around Thaksin’s home saw heightened security, with traffic police and plainclothes officers out in force. Metal barriers were placed around the residence, upon orders from Police Gen. Torsak Sukvimol, the national police chief.

“His visit was personal, but given his status as a former head of state, orders were given for officers to provide external security,” Torasak said. “Coordination was made with security officials to ensure protection and facilitate the visit.”

Cambodian activists in Thailand

Sitanan Satsaksit, the sister of Wanchalearm, a Thai activist who went missing four years ago while hiding out in Cambodia, was waiting on the sidewalk about 1 kilometer from Thaksin’s home. She said she was there to submit a letter to Hun Sen about her missing sibling, who is feared to have been abducted.

“We came to demand justice, given that Wanchalearm disappeared while Hun Sen was prime minister,” she told BenarNews.

“Cambodia claims to be investigating, but why haven’t they informed the family? We want to ask about the progress and insist the family should be informed,” Sitanan said.

Hun Sen was Cambodia’s prime minister from 1985 to 2023, the longest-serving premier in the country’s history. He retains power as president of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party and is set to become the president of the Senate following an election on Sunday.

Brad Adams, former Asia director of New York-based Human Rights Watch, told RFA that it’s likely that Thaksin and Hun Sen spoke about the thousands of Cambodians living and working in Thailand – including pro-democracy activists who have sought political asylum there.

For many years, Thailand was a relatively safe place for threatened Cambodians to hide, he said.

“What I’m worried about is that there are a lot of Cambodians in Thailand who could be at risk,” Adams said. “We’ve seen that the Thai authorities have been cracking down on Cambodians living in Thailand who are critical of the Cambodian government.”

Edited by Taejun Kang, Elaine Chan and Matt Reed.