However much Prime Minister Hun Sen might rail against Cambodian politicians holding dual nationality, a second passport is fast emerging as the must-have status symbol among even his closest allies.

Most popular has been sunny Cyprus, an island nation and European Union member state located in the Mediterranean Sea. Previous reports have found that Hun Sen’s niece, chief of police, finance minister, two personal advisors and a senator from his Cambodian People’s Party were all granted Cypriot passports in early 2017.

But not all Phnom Penh’s power players have been so successful at diversifying their passport portfolio. Former CPP lawmaker and Transport Ministry secretary of state Ing Bun Hoaw also sought a European passport in 2017. Unlike his former colleagues, though, Ing was hoping to become a citizen of Malta, another EU member state whose border is lapped on all sides by the waves of the Mediterranean. Unlike his former colleagues, his bid was unsuccessful.

The passport brokers

Assets tied to senior Cambodian political figures totalling more than $230 million have been uncovered by RFA as part of a wide-ranging and ongoing investigation into the CPP elite’s ties to Singapore, a financial hub two hours flight from Phnom Penh. Among those assets were more than $30 million linked to Ing’s wife Heng Sokha. It was in the prosperous city state that Heng launched her family’s quest for a second passport – demonstrating how Singapore functions not just as a piggy bank to Cambodia’s rich and powerful, but also as a gateway to the jetset world of second passports and offshore banking.

In early 2017, Heng contacted the Singapore office of Henley & Partners, a Swiss consultancy that prides itself on being “the global leader in residence and citizenship by investment.” Heng has substantial business interests in Singapore, and the consultancy acts as a broker between countries looking to sell citizenship and wealthy individuals seeking to buy it.

Later that year, Henley & Partners suffered a leak of some 617,000 internal files. Those files were made available to journalists and researchers through the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project's Aleph Database in June of this year. Amid those hundreds of thousands of files are 32 that document Heng and her family's interactions with Henley & Partners up until the leak. A review of those files by RFA forms the basis for this story.

Heng was interested in getting Maltese passports for herself, her husband and their five children under the island’s Individual Investor Programme, which offered a path to citizenship in exchange for a 650,000-euro (roughly $650,000 at present exchange rates) contribution to the country’s “National Development and Social Fund.” Additional contributions of between 25,000 and 50,000 euros were also required for each dependent included on the application.

A quote prepared for Heng by Henley & Partners on March 2, 2017, estimated the total cost to the family at just over 1 million euros. But it did not take long for Henley & Partners to notice there was something interesting about their application.

“Our DD [due diligence] found that her spouse is/was a Secretary of State,” an associate at the firm’s Singapore office wrote to her colleagues in Malta in an email dated March 10, 2017. “Please update me on your findings.”

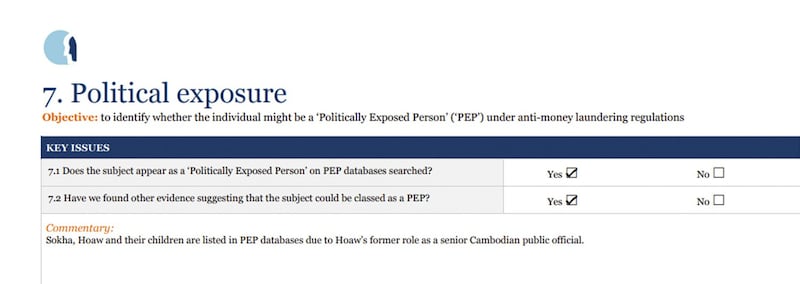

Four days later a senior compliance official at the firm responded. They had conducted their own checks and “identified Mr. Ing as a PEP.”

The three-letter acronym stands for “politically exposed person” and refers to anyone who through their holding of high office – or their proximity to those who do – is at greater risk of being involved in bribery or corruption. Businesses such as banks and law firms that process large transactions on behalf of clients use the term to flag customers for enhanced scrutiny.

At a cost of 5,000 euros to Heng, the company ordered a “background verification report” on the couple from Risk Advisory, a due diligence consultancy. The 12-page report came back in July 2017 giving the couple the all-clear.

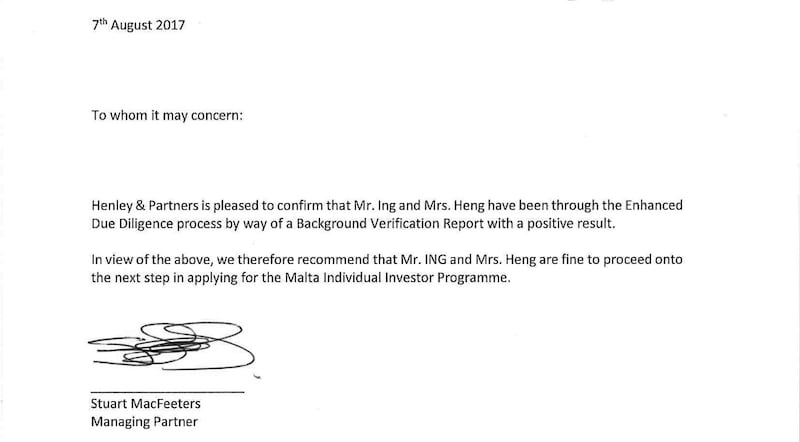

That clean bill of health was clearly important to Ing and Heng. Internal Henley & Partners emails show that the couple’s representatives pushed the immigration brokers to write a letter attesting to their having survived scrutiny. The company, seemingly confused at first by the request, eventually relented.

“To whom it may concern,” they wrote. “Henley & Partners is pleased to confirm that Mr. Ing and Mrs. Heng have been through the Enhanced Due Diligence process by way of a Background Verification Report with a positive result.”

“In view of the above, we therefore recommend that Mr. ING and Mrs. Heng are fine to proceed onto the next step in applying for the Malta Individual Investor Programme.”

Such a letter can be very useful for someone wanting to avoid scrutiny while moving large amounts of money, according to money laundering and financial crime researcher Richard Smith.

“Perhaps to open a bank account. Or just as a thing to be able to wave at an estate agent or anywhere you wanted to transact some money, it wouldn’t do any harm to have that in your back pocket,” Smith told RFA.

But in at least one endeavor it was useless. While Henley & Partners and Risk Advisory both gave the family a green light to proceed with the citizenship-by-investment process, the Maltese government disagreed.

“The application was refused by the Maltese government minister responsible for citizenship,” Sarah Nicklin, Henley & Partners’ head of PR, told RFA by email.

Nathalie Attard, a civil servant with Malta’s Home Affairs Ministry, told RFA by email that the ministry would neither confirm or deny that Heng and Ing ever submitted a citizenship application. She added that, in accordance with the Maltese Citizenship Act, “the Minister does not assign any reason for the grant or refusal of an application for Maltese citizenship.”

Nicklin stressed that responsibility for due diligence “lies with the relevant sovereign state” and any checks carried out by the company were “only preliminary ahead of processing by government.” Nonetheless, she said Henley & Partners had invested “significant time and capital in creating a corporate structure that is wedded to best practice governance and the highest levels of due diligence, even before passing a client over to the consideration of a sovereign state.”

The Maltese government’s own checks employ such an “exceptionally high level of scrutiny” that its citizenship-by-investment program had a 25-50 percent rejection rate, according to Nicklin.

“It would thus be wrong to insinuate or infer that there is weak due diligence in the programmes run in Malta or elsewhere, or that it is an easy way for wealthy criminals to subvert the law,” she added. “The contrary is the case.”

Neither Ing nor Heng responded to phone calls, text messages or emails seeking comment for this story.

Going global

But while the couple’s dreams of Maltese citizenship were dashed upon the government’s rigorous scrutiny, the rejection was a brief hiccup in the internationalization of the family’s footprint.

Heng in particular has embraced the jetset lifestyle. Her Instagram profile is awash with images of her on private jets. In several photos she is pictured carrying a Hermès Birkin bag that sells for $95,000. The couple's children have also been educated at British private schools and universities in England and Belgium.

The September after she was rejected by Malta, Heng incorporated Daun Penh Pte Ltd in Singapore. The company does not publish annual accounts, but publicly available information suggests it controls investments greater than its $31 million of paid-up share capital, an RFA analysis found earlier this year.

In 2020, she acquired Connectum Ltd, a British payments services provider that acts as a middleman between retail businesses, their customers and credit card companies. Her acquisition of the company was first reported by RFA in May 2021, when it was revealed the company's former owners had ties to fraud and financial institutions implicated in large-scale money laundering. Seven months later, RFA published details of police and banking records, as well as correspondence by Connectum's management, suggesting the company had allowed millions of dollars in criminal funds to pass through its accounts.

Whatever it was about Heng that made the Maltese government squeamish, the UK’s Financial Conduct Authority does not seem to share their concerns. All changes of ownership at British financial services firms must be approved by the FCA. According to Connectum’s most recently published accounts, Heng’s takeover received that approval.

A spokesperson for the FCA declined to comment, saying the agency is “unable to comment on individual firms.” Connectum did not respond to a request for comment on the Maltese government’s rejection of their owner’s citizenship application.

Dual nationality, a useful scapegoat

Hun Sen’s dislike of dual nationality among politicians is nothing new, even if its animus has evolved through the years. He railed against the practice during a May 1996 press conference.

"When one wife is angry with him, he runs to the embrace of the other wife. He steals things from one place and keeps them in the other place,” he said. “Politicians should have only one nationality in order to be fully responsible to the nation and to maintain equity between two nationalities."

At the time he was the junior partner in a fractious coalition with the royalist FUNCINPEC party, many of whose leading lights had not long before returned from decades overseas. The CPP was attempting to force through a clause in the Nationality Law that would exclude dual citizens from political leadership. The party talked up national security concerns over divided loyalties and a sense that the recent returnees had lived the good life as refugees and not shared in ordinary Cambodians’ suffering during the Khmer Rouge and subsequent Vietnamese occupation.

But it was clear that whatever ideological motivations the CPP might have espoused, the push had more calculated aims. Cambodia was two years away from its second national election in decades. The CPP had lost the popular vote at the first in 1993 and was only now in government having blackmailed FUNCINPEC with the threat of civil war. Had the clause gone through, it would have forced some of Hun Sen’s most popular opponents to choose between their second passport and political office.

A quarter of a century later, there is no meaningful parliamentary opposition to the CPP. Today, Hun Sen perceives the greatest threat to his rule as coming from within the upper reaches of his own party. In October of last year, he forced through a constitutional amendment restricting some of the highest offices in the kingdom to individuals holding only Cambodian citizenship. From then on, the dual nationals that make up so much of Cambodia’s ruling class would be prohibited from becoming prime minister, president of the National Assembly, the Senate, or the Constitutional Council. Whether the law will stem the flow of senior party officials seeking to convert the riches they’ve amassed at home into second passports for themselves and their children overseas remains to be seen.