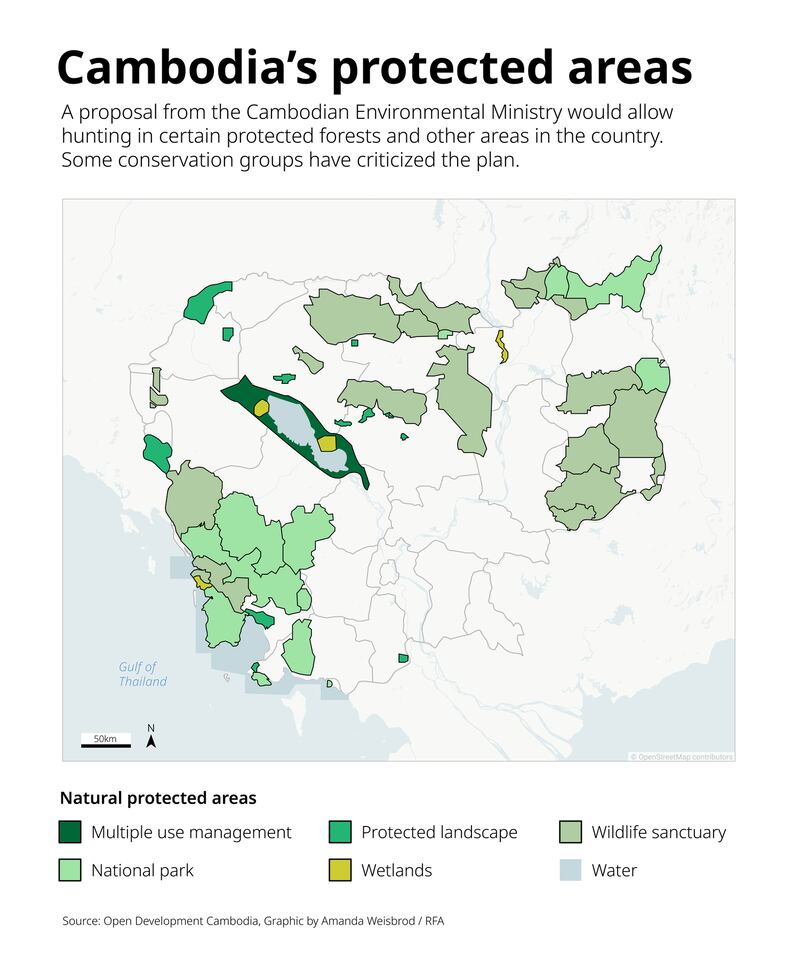

Hunting in Cambodia’s protected areas and forests would be legal in some cases under a proposal from the country’s Ministry of Environment that conservation groups fear could lead to abuses that threaten wildlife populations, according to drafts of rule changes seen by RFA.

The ministry is currently floating amended versions of the Law on Forestry and the Law on Protected Areas, which govern the Kingdom’s forest reserves and wildlife sanctuaries, respectively.

Proposed updates to the Law on Forestry would allow “game hunting on forest reservations owned by the State and other areas with appropriate permission,” the draft proposal states. The amendments stipulate that any hunting “must not greatly affect wildlife populations” and would only be allowed with letters of permission issued by the Ministry of Agriculture specifying quotas for how many of each species can be hunted, when and where.

If amended, the Law on Protected Areas would also allow game hunting as part of “projects that manage conservation and natural resources in protected areas,” provided it was conducted with Environment Ministry approval and in consultation with “all key relevant stakeholders.”

Potential for abuse

The existing legislation allows for some seasonal hunting within the country’s forests but prohibits all killing of animals within protected areas.

Amos Courage, director of overseas projects at British conservation charity the Aspinall Foundation, said the proposed changes are unwarranted.

“The whole point of a national park is that it excludes that sort of activity,” Courage told RFA. “I can’t think of any species in Cambodia that you would have a valid reason for hunting. The only reason that might be given would be revenue generation.

“It never ends up with the right people, every time there’s monetization of wildlife the possibilities for corruption are so large,” Courage added.

The Environment Ministry’s proposals have surfaced at an awkward moment. Just weeks ago, the head of Cambodia’s Forestry Administration and one of his deputies were charged by U.S. prosecutors with facilitating the smuggling of endangered long-tailed macaques.

The agency would be responsible for policing licensed hunters under the proposed amendments to Cambodia’s Forestry Law.

Path to approval

The proposed changes would have to get approval from both the country’s Council of Ministers and its National Assembly, which is controlled by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s Cambodian People’s Party, to become law.

Nick Marx, a conservationist who has worked in Cambodia for 20 years, said he does not support licensing hunters, for the time being at least.

“It seems unwise from a conservation perspective for the Cambodian government to implement a law legalizing hunting,” Marx said.

“All of the large charismatic megafauna are either extinct in Cambodia or IUCN-listed as endangered or vulnerable,” Marx added, referring to the International Union for Conservation of Nature. “With this in mind it would seem more sensible over the short to medium term to prohibit hunting and conserve our remaining wildlife.”

Endangered species

Tigers were declared extinct in Cambodia in 2016. Cambodia's national animal, the kouprey, a species of wild cattle, is widely believed to be extinct. Most of the country's endangered species, which include elephants, Indochinese leopards, wild water buffalo and Eld's deers, have been hunted to the point of extinction.

Environment Ministry spokesman Neth Pheaktra told RFA that he could not comment on the proposed amendments until they were adopted. He said that he could not give a timeframe for when or if that adoption might take place.

For Carl Traeholt, Southeast Asia program director for Copenhagen Zoo, the situation is not black and white.

“In many countries where you have local communities that are frontliners in their own environment, they have been hunting for survival for generations,” Traeholt said. “I don’t think it’s my right to tell them they can’t do that, so long as it doesn’t undermine the survival of that particular species.”

Hunting happens

Subsistence hunting is already taking place within Cambodia’s protected areas.

A 2020 study of Keo Seima Wildlife Sanctuary in Cambodia's east found that, regardless of licensing, hunting is already taking place in Cambodia's protected areas.

Researchers carried out interviews with 705 families living within Keo Seima and found that while only 9% admitted to hunting, 85% reported consuming wild-caught meat and 70% said they preferred it. The study’s authors noted that more than half of the respondents were unaware that hunting was illegal.

Cambodia’s wealthy and powerful have been known to stalk the country’s wildlife for sport. In 2017, photos emerged online of Prime Minister Hun Sen’s son-in-law Sok Puthyvuth posing with an assault rifle and an assortment of animal carcasses.

Strict quotas

There is potential for licensing and regulation of hunting to play a role in conservation in Cambodia, Traeholt told RFA, but several criteria would have to be in place in order to do so.

“When it comes to hunting in Cambodia, I don’t blame them for putting it on the list of things that could be allowed as a tool in the box, it’s another thing to do it,” he said. “I think they need to do a lot more homework.”

According to Craeholt, before regulated hunting could be beneficial, Cambodian authorities would have to enforce strict quotas and monitor wildlife populations and they should direct most of the fees and meat from the hunting to local communities.

“My main concern is I don’t really know what kind of species they can hunt without having population issues. Everything is almost hunted out as it is in Cambodia, so it’s not the first thing I’d think of for conservation,” Traeholt said.

“Many of us are a little bit skeptical about the motives behind this kind of thing. Knowing Cambodia, you always get a little bit suspicious about the motives behind it,” he said. “Unfortunately Cambodia is not a place where the governance is of the right quality.”