In August 1990, one year before he took up his role as U.S. ambassador to Cambodia, Charles Twining wrote that “the Phnom Penh regime is … acquiring a significant reputation for corruption.” Three decades later the country has the same prime minister, Hun Sen, and his government the same reputation for graft. Another constant for the last 30 years has been the apparent willingness of outwardly respectable banks, realtors and consultants to help politically connected Cambodians expatriate their country’s riches.

In recent months, an investigative series by Radio Free Asia examining the overseas real estate holdings of Cambodia’s ruling elite has turned up properties worth $30 million. Upcoming stories will reveal further properties, worth in excess of $100 million.

That figure is just a drop in the ocean of wealth that leaks out of the country illicitly each year. In 2016 alone, at least $1.8 billion was laundered out of Cambodia, according to an analysis by U.S. think tank Global Financial Integrity.

Cambodia is not alone. Global Financial Integrity estimates that economies around the world hemorrhaged more than $800 billion just in 2017. The global financial system is hardwired to facilitate the movement of capital across international borders as seamlessly as possible, and for as long as it’s been that way there have been well-dressed criminals taking advantage of it.

From Phnom Penh to Panama City

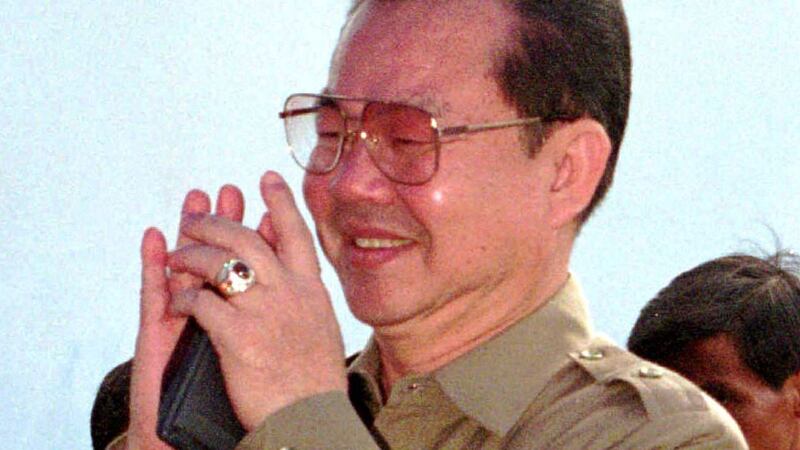

Few names symbolized the symbiosis of political power and commercial clout in 1990s Phnom Penh quite like Teng Boonma. When in 1997 Hun Sen orchestrated a bloody coup against his royalist coalition partners, Boonma admitted – but later denied – that he had stumped up more than $1 million to bankroll the bloodshed. Many observers viewed the cash as payback to a regime that had protected his lucrative businesses that skirted both sides of the law. He was a major importer and exporter of consumer goods and, according to the U.S. State Department, narcotics – a charge he repeatedly denied.

Having spent much of his life in Thailand, like many of Cambodia’s early tycoons he began cutting informal deals with the country’s government in the 1980s, before the economy had officially opened.

It was an open secret at the time that commercial success in Cambodia was only possible with political patronage, which came at a price. A 1994 internal memo from international cigarette manufacturer British American Tobacco stressed the “importance of Government, Provincial official contacts” for doing business in Cambodia, but cautioned, “it’s clearly somewhat of a ‘Pay your money, take your choice’ situation, as to who today of ‘influence’ will be in the same position tomorrow.”

What was true in 1994 was truer still five years earlier, but corporate records obtained by RFA show that did not deter lawyers in Hong Kong – then a British colony – from helping Boonma register and administer a string of Panamanian companies in 1989 to manage his commercial affairs. Meanwhile in Panama, Boonma shared a corporate lawyer with Osama bin Laden’s half-brother.

Passports to freedom

A decade later in 1999, Boonma found himself in trouble with authorities in Hong Kong, where many of his businesses were headquartered, when prosecutors charged him with making false statements to immigration officials. Somewhat ironically, they were forced to drop the charges when the tycoon claimed immunity on the grounds he held a Cambodian diplomatic passport.

Cambodia’s then-foreign minister Hor Namhong told a parliamentary committee the following year that only 10 percent of Cambodia’s 4,000 diplomatic passport holders were genuine diplomats. The remainder had been given their passports as political favors. Most used them simply to avoid the onerous visa requirements ordinary Cambodians were frequently subject to, but a less scrupulous minority put them to work as real life get-out-of-jail-free cards.

Twenty years later, Cambodian diplomatic passports have lost much of their usefulness and the trend has been reversed. Today, the must-have travel document for Phnom Penh’s well-heeled residents is a second passport – preferably one that grants the bearer visa-free access to the European Union.

Over the last quarter of a century what is euphemistically referred to as ‘global citizenship’, the controversial practice of countries granting passports to wealthy foreigners in return for investments in the local economy, has grown to be a $25 billion-a-year industry.

In 2018, one of the industry’s pioneers, Swiss consultancy Henley & Partners, held a seminar in Phnom Penh’s $230-a-night Sofitel Hotel. Following an opening address by a representative of the Cambodian Ministry of Commerce, Henley & Partners evangelized to a room full of wealthy Khmer and their business agents on the perks of purchasing passports from six Caribbean nations, two small countries in Eastern Europe and a pair of island states in the Mediterranean.

According to Henley & Partners public relations director Paddy Blewer, there are two principal reasons why a wealthy individual from a country such as Cambodia might want a second passport. The first is to shake free of the same visa restrictions that users of Cambodian diplomatic passports were trying to evade 20 years ago. “The vast majority of investors in citizenship-by-investment and residence-by-investment programs are not [interested in] emigration,” Blewer said in an interview. “It's the, ‘I want to be able to go wherever I want to go, whenever I go, and I want to take my family with me.’”

He noted that for most people able to afford these programs, “your wealth portfolio is almost certainly, if not nationally, then regionally based … so you don’t leave [home]. You only leave if you’re forced to leave.”

For some, a second passport acts as “an insurance product,” Blewer said. “If you come from a part of the world where there is constant volatility, either politically, environmentally or financially, you might want to [be able to] get out quickly.”

This would appear to be the motivation for many of Cambodia’s ‘global citizens’. When a Reuters investigation revealed last October that eight politically connected Cambodians had acquired Cypriot passports by investment, a government source in Phnom Penh told the news agency, “Everyone is making an escape plan.”

The government of Cyprus has since announced its intention to revoke the eight Cambodians’ passports. Blewer insisted the firm had nothing to do with the individuals in the Reuters story. He stressed that while Henley & Partners has helped wealthy Cambodians acquire second citizenships, none were what is known as ‘politically exposed persons’, or PEPs.

PEP is a designation used by law enforcement and corporate compliance professionals to identify individuals who either hold high public office or are close relatives of people who do. In most jurisdictions, professionals and individuals offering financial services are obliged to conduct enhanced due diligence before handling transactions with PEPs.

While Henley & Partners conducts due diligence on all its clients as a matter of course, not all citizenship brokers are so discerning about whose money they take, according to Blewer, who said the industry is currently under-regulated.

“There is no regulation that says you’ve got to check who you’re working with. We could, as a number of our competitors do, just take anyone’s money,” Blewer said. “Because there is a lack of global regulation, or even national regulation, the primary due diligence responsibility in citizenship and residence-by-investment is held by the sovereign state that runs the program.”

Banking on the ‘Khmer Riche’

Cambodian national police commissioner Neth Savoeun and his wife, Hun Sen's niece Hun Kimleng, both featured prominently in the Reuters expose. RFA subsequently revealed that Kimleng bought €2.5 million in Cypriot real estate at the start of this year.

Ten years earlier, the day after her husband’s 50th birthday, Kimleng bought a £1.95 million ($2.4 million) apartment on the fifth most expensive street in the United Kingdom, in the tony London borough of Kensington. Deeds lodged with the UK Land Registry record that the purchase was financed by a mortgage from Singapore’s United Overseas Bank.

The bank did not respond to repeated requests for comment on how a sizeable loan to the wife of the most senior policeman in a noted kleptocracy cleared due diligence. In 2017 the Monetary Authority of Singapore fined UOB close to half a million dollars over its failure to comply with anti-money laundering regulations.

Put on notice

Cambodia itself is under growing international pressure to clean up its act on money laundering. In May, the European Union’s executive branch listed Cambodia alongside 19 other countries as deficient in tackling the problem. The listing placed Cambodia alongside such notorious offshore havens as the Bahamas, and Teng Boonma’s favourite jurisdiction, Panama, as well as failed states such as Yemen and Syria.

The National Assembly passed two bills on June 4 to strengthen Cambodia’s legislation on countering money laundering and financing related to the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction. The bills were drafted without consultation with civil society groups and had not been made public before lawmakers voted on them. According to the government, the legislation allows for prison terms of up to 20 years and fines of up to $50,000, and provides for more stringent measures on freezing and confiscating assets and requires more background checks on bank customers.

Cambodia was already on notice from the Paris-based Financial Action Task Force (FATF), which placed the kingdom on its money laundering “grey list” in February 2019. Cambodia needs to adopt the new legislation quickly to meet the requirements of the FATF’s action plan.

Among several factors behind the listing, the FATF pointed to a lack of oversight in Cambodia's booming real estate and gaming sectors as a crucial failing. Cambodian officials conceded last year that the country's seemingly unstoppable property boom was fueled by money laundering.

But when the political class is so frequently the beneficiary, it seems unlikely serious action will be taken any time soon.

Sovannarith Keo contributed to this report.