The U.K.’s ‘Russia Report’ reveals London as a kleptocrat’s paradise, which may be why it’s such a magnet for politically connected Cambodians with cash to spare.

A parliamentary intelligence committee recently highlighted how President Vladimir Putin’s Russia wields malign influence inside the United Kingdom – and not just through disinformation and deadly spy-craft.

The committee’s report also examined how Putin’s agents and allies – and crucially, their money – have infiltrated the business, social and political life of London, and how vulnerabilities in Britain’s legal and commercial infrastructure have made London a mecca for kleptocrats and their entourages the world over.

On the money and influence side of the equation, the so-called ‘Khmer Riche’ appear to be following the same playbook. During an ongoing RFA investigation into the foreign real estate accumulated by the family of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and his cronies, London has come up time and again. Relatives of the Cambodian leader and those with deep connections with his security state have taken advantage of lax U.K. regulations to park their wealth in London real estate with few questions asked.

An open-door policy, at a price

In 1994, the U.K. introduced ‘investor visas’, allowing just about anyone willing to invest £2 million ($2.5 million) in the British economy to stay in the country for three years and four months. The Russia Report claims that the introduction of these pricey entry permits -- known as ‘Tier 1 (investor) visas’ were instrumental in attracting wealthy Russians to Britain. Twenty years later, the U.K. granted some 120 Russians investor visas in 2014 alone.

The following year, in 2015, the British government issued an investor visa to Neth Thida Chanthima, the then-20-year-old daughter of Cambodia’s national police chief Neth Savoeun and his wife Hun Kimleng, who is Hun Sen’s niece.

Accused of severe human rights abuses in the service of propping up Hun Sen’s government, Savoeun, his wife and their three children were hit with visa bans by the U.S. State Department in 2017 for “undermining democracy,” effectively barring them from entering America, according to Reuters.

The British government does not seem to have been troubled by any such concerns. Chanthima continues to live in London, where she is pursuing a doctorate and is frequently visited by her family members.

The Russia Report, however, found that the investor visa program needs an “overhaul,” suggesting too many bad apples were entering the U.K. off the back of it.

“There needs to be a more robust approach to the approval process for these visas,” the report said.

‘The prosperity agenda’

Investor visas were one of several vulnerabilities identified by the authors of the Russia Report in what they described as successive British governments’ “prosperity agenda.”

Under this agenda, for the sake of swelling the U.K. economy, foreign capital has been welcomed into the London real estate and investment markets with little in the way of oversight or regulation.

“Few questions – if any – were asked about the provenance of this considerable wealth,” the report claims.

Members of Cambodia’s upper crust have sunk dizzying sums into London's luxury property market.

This approach, it continues, “offered ideal mechanisms by which illicit finance could be recycled through what has been referred to as the London ‘laundromat’.”

A key component of that laundromat is the city’s luxury property market, a market into which Cambodia’s upper crust has sunk dizzying sums.

In September 2017, Chanthima’s older sister, Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs official Neth Vichhuna, bought two adjoining luxury flats in Kensington for £5.5 million ($6.9 million). Title deeds for the property obtained by RFA indicate the then-24-year-old bought the property without a mortgage, suggesting she had almost $7 million to hand in cash at the time.

In a recent interview with RFA, Lee Morgenbesser of Griffith University said that whenever millions of dollars leave Cambodia, it is likely the money is somehow tainted.

“If that amount of money is coming from anywhere in Southeast Asia, with the exception of Singapore, it’s likely to be dirty as a result of corruption, or nepotism or embezzlement,” said Morgenbesser, author of a book on Southeast Asian dictatorships.

Cash for access

When not crisscrossing the globe on private jets, their aunt Hun Chantha lives just 50 meters from Vichhuna’s London bolthole in an apartment worth in excess of $5 million. As detailed in an RFA investigation published in December, when in Britain's capital city Chantha keeps a busy social schedule and is frequently photographed at high society charity functions where champagne and altruism flow in tandem.

In London, though, sometimes even altruism can have a dark side, according to the Russia Report. Its authors found that money of dubious origin arriving there frequently gets funneled into ‘reputation laundering’. By splashing their cash on charitable, cultural and political organizations, dubious characters with links to Vladimir Putin can get a foothold in elite British social, political and business circles.

In 2015, Chantha, a niece of Hun Sen, footed the bill for a charitable lunch thrown for several British members of parliament, the RFA investigation found.

The ability of moneyed foreign elites to essentially buy facetime with British politicians through donations gives them a direct line to the country’s policy makers, according to Moneyland author Oliver Bullough.

“If you have a 10 minute conversation with someone, and they explain what they're doing, then you're much more likely to see their point of view,” Bullough said in an interview with RFA.

“That's why it's worth paying to get a seat next to a minister at a table because it isn't really about bribing them, it’s just about asking them to see your point of view – and it's amazingly successful.”

‘The most corrupt place on Earth’

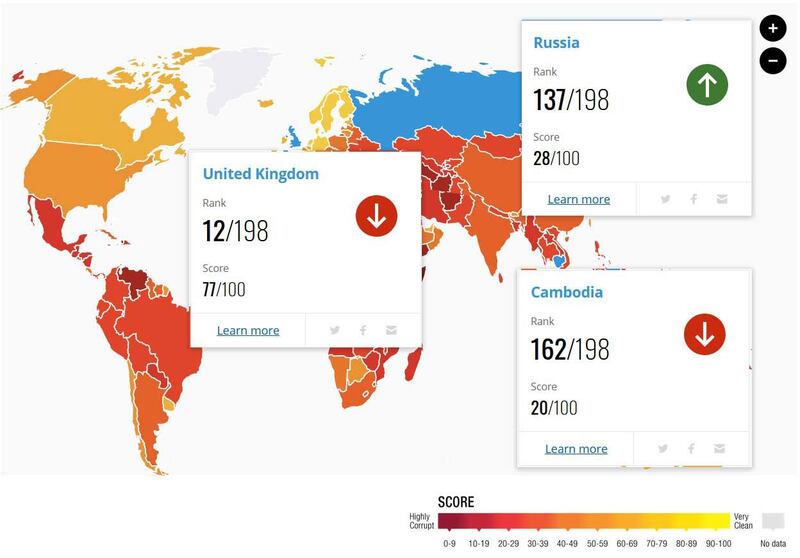

By most traditional measures, Cambodia and Russia are far more corrupt places than Great Britain. This is reflected in global rankings such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, in which the U.K. scores 12th best, while Moscow comes in at 137th and Cambodia 162nd out of 198 countries.

But in 2016, Italy’s most renowned mafia journalist, Roberto Saviano, proclaimed Britain “the most corrupt place on Earth,” thanks to the ease with which the proceeds of crime can be washed clean through its capital city.

“The City of London is a far more important center for laundering criminal money than the Cayman Islands,” he said in an interview with the Guardian, referring to an offshore financial haven in the Caribbean.

While the ritzy streets of London’s financial center seem a world away from gang-plagued ghettos, the criminal violence and political corruption that its financial infrastructure has helped to make so profitable is coming home to roost.

‘From Russia with Blood’

A 2017 investigation by BuzzFeed — “From Russia with Blood” — raised concerns that 14 deaths of Russian expatriates and their British associates were the result of a Moscow-directed assassination campaign. The Russia Report noted that the chair of the British parliament’s Home Affairs Select Committee described BuzzFeed’s reporting as founded upon “considerable concerning evidence.”

Several moneyed Cambodians with allegedly violent or otherwise nefarious pasts have turned up in London in recent years, most of them paying visits to at least one of the Kensington apartments.

Neth Savoeun has paid visits to his wife's £1.95 million ($2.4 million) apartment, purchased the day after his 50th birthday. Human Rights Watch has labelled the national police chief as one Cambodia's “Dirty Dozen” generals over his alleged role in torture and summary executions.

For years, Savoeun's brother-in-law Hun To was denied a visa to Australia, reportedly over his alleged involvement in drug trafficking. Despite repeatedly denying the allegations, To has been unable to shake them and as recently as this April calls were being made in Canberra for the Australian government to place him under sanctions.

Again, any such concerns did not appear to have impeded his ability to stroll the streets of London, where he was photographed in 2018.

The previous year, a Cambodian diplomat was asked to leave the U.K. after local police accused them of “possession of a firearm with intent to injure,” Britain’s then-foreign secretary disclosed to parliament.

The U.K. Foreign Office was approached for comment regarding the incident but a spokesperson said it does not comment on individual cases.

Two countries, one system

In its introduction, the Russia Report describes its subject nation as “both very strong and very weak,” ascribing its strengths to its victory in World War Two and its status as the inheritor of the Soviet Union’s achievements. Cambodia has no similar claim to recent victories, except perhaps the defeat of the Khmer Rouge, whose former commanders now permeate its government. But in many respects, Phnom Penh and Moscow are alike.

Giving evidence to the Intelligence and Security Committee, Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service described the “muddy nexus between business and corruption and state power in Russia.” A similar statement could be made about Cambodia, where business success is often predicated on having paid up a patronage pyramid whose capstone is Hun Sen.

Many of Putin’s key allies in London are drawn from his former colleagues in Russia’s intelligence service. Similarly, some elite Cambodians with their fingers in London real estate have deep connections to Hun Sen’s security state.

A 2017 investigation by BuzzFeed — From Russia with Blood — put a spotlight on sinister allegations of a Moscow-directed assassination campaign.

Witness the fact that Hun Kimleng and Neth Vichhuna, wife and daughter to Cambodia’s most senior police officer, have a combined London property portfolio worth in excess of $10 million. And Hun Chantha, owner of close to $7 million of London real estate, although now remarried, was once married to the now-head of the Cambodian Interior Ministry’s Central Security Department, Dy Vichea. His promotion to that position was signed off on by none other than Chantha’s brother-in-law, the national police chief Neth Savoeun.

The Russia Report likened any possible attempt to combat malign Muscovite influence in the U.K. to shutting a stable door after the horse has bolted. Will Phnom Penh's emissaries to the Kensington property market establish the same firm foothold that Moscow's Mayfair mobsters have?