Call it the Telegram election.

In late June, just as he was starting to campaign for the July 23 national election, Cambodia's long-ruling Prime Minister Hun Sen deleted his Facebook page.

It was a pre-emptive move: Meta’s oversight board recommended his account be suspended after he posted a video threatening violence against his opponents. So Hun Sen told his supporters to migrate to Telegram.

There, he’s been treating his nearly one million followers to an endless stream of photos of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party’s (CPP) election campaign. The images come so fast and so thick it’s almost impossible to keep up, let alone to comment, criticize or ask for help.

The premier's newest platform of choice makes two-way communication almost impossible. If Facebook existed as a platform for Hun Sen to attack his critics, it also served as a rare space for citizens to petition their leader directly and had become a repository of government documents and political history. On Telegram, the posts slip away almost as quickly as they appear.

Hun Sen’s move from open communication — even via a means as flawed as Facebook — to the one-way Telegram stream is a fitting metaphor for Cambodia’s seventh national election: one with no viable opposition and no routes for protest. It represents the endpoint, in many ways, of a three-decade experiment in managed democracy.

Today, with the ruling party controlling the legislature, judiciary and ministries; with the international community focused on far bigger problems elsewhere; with civil society and free media mostly silenced, Hun Sen no longer needs to hold elections where the outcome is not entirely preordained. And ahead of a play to position his son, Hun Manet, as the next leader of Cambodia, neither can he afford to do so.

Hun Sen’s 30 years of ‘democracy’

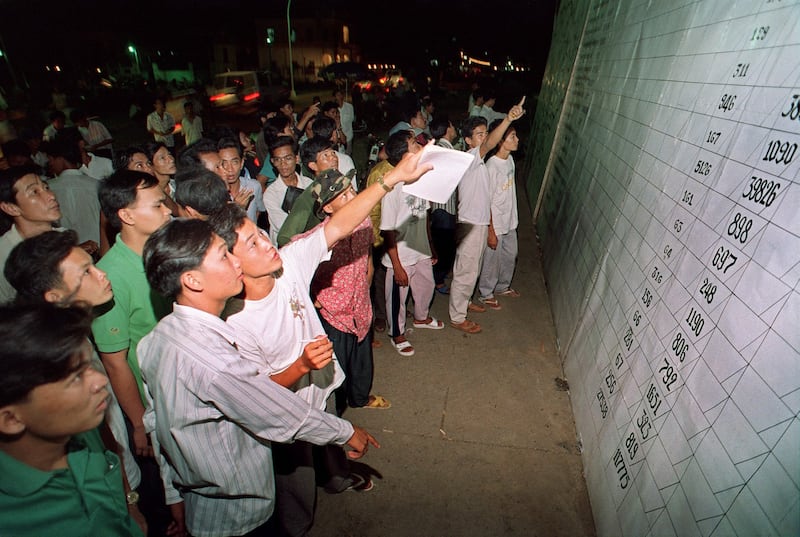

Thirty years ago, more than 4.1 million Cambodians cast their ballot in the country’s first postwar national election. Administered by the United Nations, the May 1993 vote was also the first democratic, multiparty election in decades. Despite ongoing attacks by Khmer Rouge guerillas, regular bombings, threats and an infrastructure damaged by years of war, Cambodians were eager to make their voices heard.

Some 86.8 percent of those eligible voted over the six days of the election period.

By then, Hun Sen had already served as prime minister since 1985, when the country was still under Vietnamese occupation. A low-level Khmer Rouge cadre who defected and fled to Vietnam, Hun Sen spoke frequently of having saved the country from the genocidal Khmer Rouge. In 1991, he was the government's representative at the Paris Peace Accords that paved the way for a democratic Cambodia.

Some 18 nations and the U.N. were party to the accord.

But if the international community wished to convince themselves that Hun Sen could be a democratic leader, there were signs from the start that he would jealously guard his power.

When the royalist Funcinpec party beat out the CPP in the 1993 election, Hun Sen complained of polling irregularities, then threatened a secessionist movement. It helped him maneuver his way to a co-prime minister position — "strong condemnation" by the U.S. and others did little to tamp him down.

Despite the violence leading up to it and the undemocratic result, some believe that first tilt at democracy may have been Cambodia’s best effort.

Like many Cambodians, Teap Chanthou, a resident of Pailin province, contends that the 1993 vote represents the country’s only truly free and fair election. Certainly, she said, it was far more legitimate than the one about to take place.

“Before no one bought us for ballots,” she said. “Now people are spending money."

The past few months have been an exercise in controlling the outcome, even as it was preordained by moves the government took years and decades earlier.

In May, the main opposition Candlelight Party was disqualified from running on a bureaucratic technicality that rights monitors say is politically motivated.

In June, parliament amended the election law to fine, prosecute or bar from office anyone advocating a voter boycott — effectively barring the sole avenue for electoral protest.

Lest those moves fall short, members of the opposition, along with environmental activists, political analysts and others have been jailed and beaten.

Hundreds have defected to the ruling party, amid a carrots-and-sticks effort that involves arrests, pardons and high-level appointments. After independent broadcaster Voice of Democracy was shuttered in February at Hun Sen's order, the government offered ministry jobs to former journalists.

Though 17 other parties are contesting this election, they are miniscule, underfunded or obsolete. None is positioned to receive more than a handful of votes. And while a handful of foreign observers have been approved to monitor the election, experts say they are almost certain to be " zombie monitors", whose stamp of approval strains credulity.

Strong man, weak grip

This tightly controlled political system, thinly veneered as a democracy, has been decades in the making, and Hun Sen’s machinations to secure his position are a masterclass in consolidating power.

Yet the prime minister operates with the paranoia born out of this lifetime of political experience.

“When you operate in a political environment that is so uncertain and so insecure you maximize your power at all costs,” explained Sorpong Peou, a political scientist at Toronto Metropolitan University.

Hun Sen, who will be 71 next month, counts himself among the world’s longest serving living leaders. Apart from royals, no one in Asia has outlasted him.

In his early years, he outmaneuvered his opponents through threats and violence. Over time, as the need for these muscular approaches declined, he used the newfound social realities of a more stable Cambodia to his favor.

Over the course of the 1990s and 2000s, poverty, malnutrition and infant mortality plummeted. The economy was buzzing along with more than 8 percent growth a year in the first decade of the century and calm had replaced decades of war. While his elections always contained an element of bias, he also enjoyed a genuine measure of popularity.

But today, in a rapidly developing nation where some two-thirds of the population is younger than 30, the many shortcomings of Hun Sen’s government are too clear to ignore.

Needs are both acute and unmet. The economy is still struggling post-pandemic with many Cambodians mired in personal debt. Climate change has wreaked havoc on the country's crops and fisheries, while a decade of land grabs and resource depletion have impacted hundreds of thousands of people.

In villages and cities across the country, Cambodians grumble about local officials who take little interest in their needs until an election rolls around. Then they show up with 20,000 riel ($5) and sample ballots showing them precisely which box to mark.

“I’m not busy but I don’t plan to go [vote] because the village chief is awful,” said a Pailin province resident who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons. In her community, she said, sand dredging has damaged homes, but the CPP-run local government has done nothing to address the problem.

Unable or unwilling to address such issues through governance, Hun Sen has instead doubled down on silencing those who point them out.

“Human rights defenders, journalists, political opponents and ordinary citizens now routinely face intimidation, arrest or prosecution for merely expressing their views or reporting on matters of public interest,” said Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Center for Human Rights.

Given the level of dissatisfaction, an opposition party — even a neutered one — might pose a threat, as might unhappy members of his own political elite. Hun Sen, in other words, can’t afford to take any chances.

The slipping of power

The risks to the prime minister were made clear in recent elections.

When Cambodia’s two chief opposition parties merged before the 2013 election, some observers expected factionalism and infighting to prevent any real gains. Instead, the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) captured 44 percent of the vote to the CPP’s 48 percent, catching Hun Sen and the political elite off guard.

Convinced the ruling party had stolen the election, opposition voters held mass protests and a political crisis ensued. These were shut down through police violence, arrests and prosecutions. While Hun Sen maintained his grip on power, he learned a lesson about the unpredictability of open elections.

When the CNRP made sweeping gains in the 2017 commune elections — seen as a bellwether for national elections — the government unleashed waves of suppression that also made clear how mature the prime minister’s political machinery had become.

“From 1998 to the 2017 commune election… at least you see that the opposition was able to participate and independent media was still operating inside Cambodia,” said Koul Panha.

The country’s preeminent independent election monitor, Koul Panha was forced to seek political asylum in Canada in 2018 amid worsening repression.

“Even if there was an environment of intimidation, we were still able to conduct our activities,” he said. “But certainly from 2018 the situation and political competition falls short of legitimate free and fair elections.”

Now with the courts, legislature and election commission fully under ruling party control, Hun Sen has been able to quash his opponents primarily through lawfare.

Since 2017, the Supreme Court has dissolved the CNRP, saying it had plotted a foreign-backed color revolution aimed at toppling the government. Opposition leader Kem Sokha has been sentenced to 27 years for treason, party members have fled the country and a series of arrests has resulted in mass trials and scores of convictions.

With no avenue for contesting the election within Cambodia, the opposition now holds protests in diaspora enclaves like Lowell, Mass. On social media, they urge voters to X out their ballots.

“We call on voters to go to vote but to spoil the ballot,” said CNRP vice president Mu Sochua, who, like most opposition leaders, now lives in exile. “Spoiling the ballot for justice means that Hun Sen won't be legitimized, that Hun Manet won’t be legitimized.”

Setting up the heir apparent

Legitimacy is a chief focus for Hun Sen as he seeks to shore up his legacy by transferring power to his eldest son, Hun Manet. In 2021, Hun Sen announced that Hun Manet could be made premier sometime between 2028 and 2030, with the ruling party then officially endorsing his future candidacy.

A Western-educated four star general, Hun Manet has been meeting with a slew of foreign leaders since receiving the CPP's endorsement.

But while he is being positioned to step into his father's seat, transitions of power make for notoriously risky moments within authoritarian regimes.

Hun Sen has been shoring up support, placing his officials' children in choice positions and obtaining a raft of public endorsements.

And every few days, on his father’s Telegram channel, Hun Manet forwards his own speeches from the campaign trail.

“As the ruling party, which obliges to serve the people,” he posted recently, “the CPP has no right to rest.”

Additional reporting by RFA Khmer