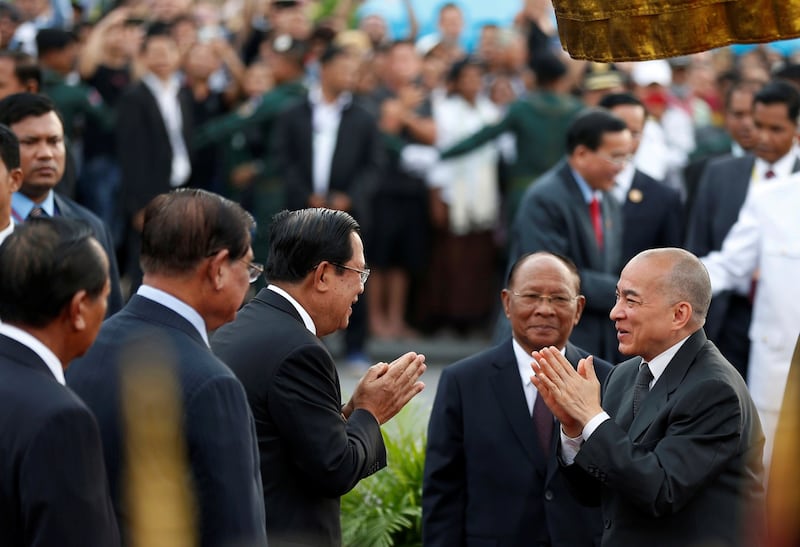

As he approaches two decades on a powerless throne, Cambodian King Norodom Sihamoni has found himself caught in a political fight between the country’s long-time strongman and a former opposition leader forced into exile.

The dispute, which began with a public mudslinging between Prime Minister Hun Sen and his political nemesis, Sam Rainsy, over who had betrayed the nation, has put a spotlight on the European-educated former dance instructor, who as king has preferred to remain in the shadows.

“I believe that King Norodom Sihamoni did not want the honor or fame as his predecessors. He did not have such ambition or greed,” Oum Daravuth, who is one of Norodom Sihamoni’s advisers, told RFA. “The king does not want his name to be as famous as others. He just wants to live in hiding; he does not want anything else.”

But the fight between Hun Sen and Sam Rainsy has broader implications than who wins a war of words. Hun Sen has threatened to dissolve the little that remains of his political opposition, which traces its roots to Rainsy, less than a year out from a national election.

It has also revived a debate over the 69-year-old’s rightful role as the constitutional monarch of a fractured parliamentary system that has been slowly deconstructed under Hun Sen’s rule.

While the king is legally required to reign as national figurehead and leave governing to the National Assembly and the prime minister’s Council of Ministers, some in the opposition have called upon Sihamoni over the years to challenge Hun Sen’s repression of their ranks.

But the king has rarely even responded to such requests, instead mostly remaining inside the royal palace, quiet and out of view.

Upon taking the throne in 2004, the king had pledged to remain close to the people of Cambodia and serve out his days promoting national unity.

“I will never live apart from the beloved people,” Sihamoni said. “The Royal Palace will remain a transparent house and, for me, there will never be an ivory tower. Every week, I will devote several days to visiting our towns, our countryside and our provinces, and to serving you.”

The quiet king

Sihamoni comes from a family that claims lineage back to the “god kings” of Angkor, when the Khmer Empire ruled much of Southeast Asia before being forced under Siamese, Vietnamese and eventually French rule.

His father, the late King Norodom Sihanouk, was also known as the “father of independence” for overseeing Cambodia’s 1953 breakaway from French colonial rule. Sihanouk later led the 1980s shadow government that opposed the Vietnamese occupation, after its army had driven the Khmer Rouge from power, and fought a civil war against Hun Sen’s government before the 1991 U.N.-brokered peace restored elections.

Sihanouk abdicated in 2004 to ensure he had a say in choosing his successor. Prince Norodom Ranariddh, whose party won the U.N.-run 1993 elections but was forced into a coalition with Hun Sen, reportedly wanted the throne, but Hun Sen preferred Sihamoni.

Lesser known than his politician half-brother at the time, Sihamoni, who was born in May 1953, had previously served as Cambodia’s UNESCO ambassador and lived in France, where he taught classical dance. As a young boy, he had been sent to study music and dance in Prague, and earned a master’s degree from the city’s Musical Art Academy.

In 1975, the year the Khmer Rouge took over Cambodia, Sihamoni went to North Korea to study filmmaking. But he soon returned to Phnom Penh, where he was kept prisoner in the royal palace with his father and Queen Mother Norodom Monineath until Pol Pot’s regime fell in 1979.

Since assuming the throne, the son has embodied the principle enshrined in the 1993 Constitution that the king “shall reign but shall not rule.”

Cambodia’s unequivocal ruler has been Hun Sen for more than three decades, and he has recently announced plans to keep that power in the family, pushing his son Hun Manet as successor after 2028.

The ‘t’ word

The recent trouble started when Rainsy said on RFA’s Oct. 25 nightly program that the king’s acquiescence to Hun Sen’s rule — and, in particular, decisions made in 2005 and 2019 to cede territory claimed by some Cambodians to neighboring Vietnam — made him an accomplice to “treason.”

“What Hun Sen uses as a ploy is to force the king to support his treason. If the king yields to Hun Sen's intimidation, and turns to support Hun Sen's treason, the king must be responsible,” he said. “If it was me, I would have abdicated, because I must not be intimidated by Hun Sen.”

Rainsy, who in 2015 fled Cambodia to his home in Paris after the government reignited a 2011 defamation conviction against him, said on RFA that Sihamoni's faintheartedness would be long remembered.

“It is dangerous for our nation that you turned out to be a rubber stamp for the traitor,” Rainsy said. “It means you contributed to committing treason, for which you must be responsible before the Khmer nation and history.”

In response, Hun Sen called for Cambodians to "stand up to oppose this traitor and any party that dares to connect with this traitor," alluding to the Candlelight Party, which was once named the Sam Rainsy Party. The prime minister has since called on members of the party to denounce their former leader, or risk their party being banned from politics.

“We must do so in order to defend the monarchy,” he said.

Border disputes

Large stretches of the 1,270-kilometer border between Cambodia and Vietnam have remained poorly demarcated since the colonial period, when both countries were part of French Indochina. Efforts to strictly define the boundaries are highly politicized and have been complicated by a belief among some Cambodians that Vietnam wants to take over their country.

Hun Sen’s personal history — as a fluent Vietnamese-speaking former communist — has fed into concerns about borders. In 2005, a “supplemental border treaty” recodified controversial treaties Hun Sen’s government signed in the 1980s — during Vietnam’s post-Khmer Rouge military occupation of Cambodia — to cede disputed territory to Hanoi.

In his first year as king, Sihamoni had initially demurred on signing the law, citing his father's opposition. But he relented when Hun Sen threatened to create a republic.

Another treaty was then signed in 2019 that further solidified the earlier treaties, with Cambodia's opposition again criticizing the law on the basis that it legitimized treaties signed during Vietnamese occupation.

The king as a pawn

Lao Mong Hay, a political analyst who previously served as an adviser to Kem Sokha, a co-founder with Rainsy of the Cambodia National Rescue Party that was dissolved in 2017, said the dust-up shows how political figures tend to try to use the king to further their own interests.

“It appears like such respect exists only as lip service, when one says they respect the king or follows the king’s ideas,” Mong Hay said.

It made little sense to suddenly bring the king into a political fight when both sides refused to “collaborate” with him, Mong Hay said.

That alone ought to shield the king from criticism leveled by politicians, who should focus on each other and keep the king above politics, said Prince Sisowath Thomico, a nephew and adopted son of Sihanouk and a former member of the outlawed Cambodia National Rescue Party.

“There’s extremism on both sides, frankly. Both from Prime Minister Hun Sen, who quarreled with Sam Rainsy, and Sam Rainsy, who went to quarrel with Prime Minister Hun Sen,” Thomico said. “All of this reflects extremism, and we will not be able to lead the nation with extremism.”

Son Soubert, a former member of Cambodia’s Constitutional Council who heads the king’s advisory council, said whatever criticisms are leveled against him, Sihamoni was not likely to enter the political fray.

“He never wanted to ascend the throne, but because there was no one else, he had to ascend to the throne,” Soubert said. “He knows his role, and he knows his duty clearly: that he may fulfill his duties as permitted by the Constitution until the day he stops existing on this planet.”

Translated by Sovannarith Keo. Written in English by Alex Willemyns.