Climate change, drought, and upstream dams have led to record low water levels on the Mekong River, according to experts, who say the shortage is significantly harming Cambodia’s Tonle Sap Lake and the surrounding fishing communities who rely on it to earn a living.

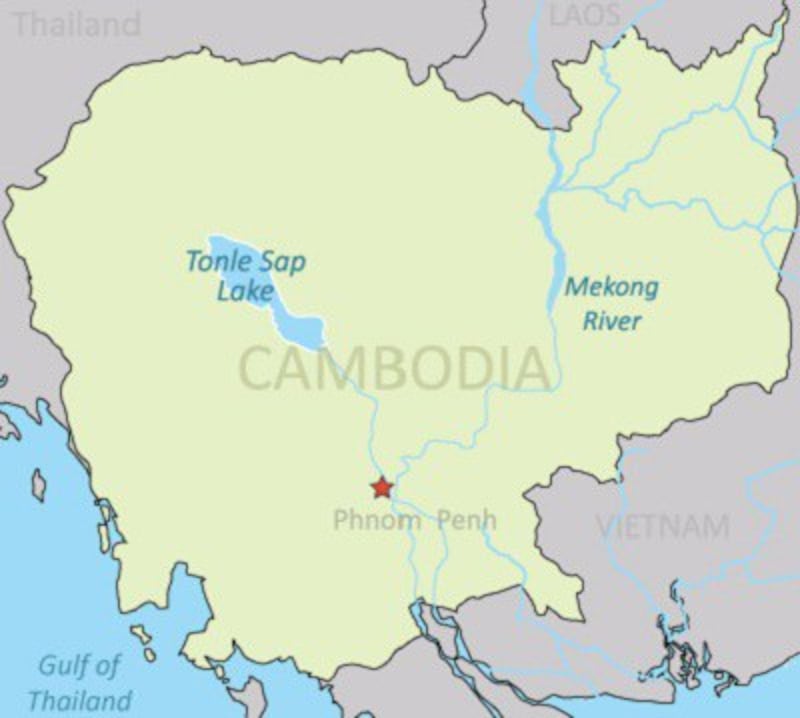

The water gauge on the Mekong at the port of Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, which lies only several hundred meters from where water from the river flows to the Tonle Sap Lake, is currently registering levels of 13 feet below average for late July and lower than last year’s record, according to local media reports.

Traditionally, heavy rains during the June-October wet season push water from the Mekong River into the Tonle Sap Lake via the 70-mile-long Tonle Sap River which reverses its flow during the November to May dry season, draining the lake into the Mekong. The Tonle Sap would normally increase its level by four times during the monsoon season.

Mao Hak, deputy secretary-general of the Tonle Sap Authority, recently told RFA’s Khmer Service that the water level of the lake is extremely low because changing weather patterns have delayed the annual reversal of the flow of the Tonle Sap River.

“We know that this year’s climate change has caused the level of the water to remain low,” he said.

“There is not much precipitation on the Mekong River and the two bodies of water are related. That is why the Tonle Sap Lake is experiencing such a low level of water.”

While the lake levels are low, Mao Hak said that so far “we haven’t experienced any serious water shortage” and water consumption “remains normal.”

The deputy-secretary general would not comment on claims by some experts that hundreds of upstream dams on the Mekong between China and Laos are also contributing to record lows on the river because of restrictions on water flow, but he said that he expects the Tonle Sap River’s flow reversal to occur sometime in mid-August.

Brian Eyler, a senior fellow and director of the Washington-based Stimson Center’s Southeast Asia program, told RFA a major drought affecting the region since January 2019 threw the timing of the reversal off beginning last year, which has dropped the lake to uncharacteristically low levels.

“This results in distress for fishing communities along the Tonle Sap as well as a lowered fish catch,” he said.

“How much lower that fish catch is really needs to be studied, but I agree that anecdotal reports from last year and this year also show that fish catches per community are down 80 to 90 percent.”

No fish to catch

Long Sochet, a fisherman and the head of the Tonle Sap Fishing Community Alliance, said the decreased catch has battered residents—particularly those who live on floating villages on the lake and have no other means to support themselves.

“With such a drought, this month there are no fish,” he said.

Long Sochet also rejected claims by Mao Hak that the region is not facing a water shortage.

“There is a shortage of water for household consumption—for drinking and bathing—let alone fishing,” he said.

“We have to dig wells in some places and there is still no water. People living on the floating villages in Tonle Sap Lake nowadays have to dig wells [on land] for water. It’s happened two years in a row, with waters receding to their lowest level.”

Chea Sarin, another fisherman and head of a fishing community in Battambang province’s Ek Phnom district, on the northwest coast of the Tonle Sap Lake, also complained of extreme difficulties due to the drought.

“There is no water, even at this time of the year,” he said. “Basically, it is like a paddy field that was just plowed.”

Hor Sam Ath, the deputy-chief of the Sdey Kraom Moha Suong fishing community—also in Ek Phnom district—said the lack of water had not only caused reduced fish catches, but could lead to the extinction of some fish species, noting that this time of year is when fish typically lay eggs in conservation areas of the lake.

“There are a lot of illegal fishing activities on the Tonle Sap,” he said. “When the water is low and fish lay eggs, the juveniles become victims to illegal fishing nets.”

According to Cambodia’s Fisheries Administration, the country’s freshwater fish catch volume in 2019 was 470,000 tons—around 50,000 tons less than a year earlier. The administration has attributed the decrease to climate change.

On July 14, while speaking at a fish species research and development center in Prey Veng province, Prime Minister Hun Sen acknowledged that the country’s fish catch volume is decreasing, which he said was due to “manmade and environmental factors,” including climate change.

Upstream dams

Ham Oudom, a consultant on natural resources and water governance, recently told RFA that in addition to climate change, massive dam construction on the upper Mekong river—particularly in China and Laos—is also a contributing factor to low water levels on the Tonle Sap.

“They build dams upstream and also need water for their own countries’ consumption, so the water level downstream is reducing,” he said, adding that the decrease has been noticeable “over the past few years.”

“This isn’t simply about water—it also relates to economic issues, as people are becoming even more indebted to microfinance institutions.”

Stimson’s Eyler agreed that upstream dams are compounding the effect of the drought.

“China has some of the largest dams in the world and we are seeing that, once again, for a second year on record, that China’s upstream dams are preparing to restrict more than 20 billion cubic meters of water from the downstream,” he said.

“That’s a contributing factor to the low-level conditions along the Mekong mainstream, as well as the late reversal to the Tonle Sap Lake.”

In April, Eyes on Earth, Inc. and Global Environmental Satellite Applications, Inc. issued a joint report based on satellite data from 1992 to 2019 and daily river height gauge data from Thailand which found that 126.44 meters (415 feet) of river height was missing at the gauge over the 28-year record.

The report noted that a Chinese state-owned enterprise had built a series of dams on the Mekong during that time.

“The relationship between gauge height and natural flow deteriorated after 2012, when a couple of major dams and reservoirs were built, which greatly restricted the amount and timing of water released upstream,” the report said.

According to the study, the severe lack of water in the Lower Mekong during the wet season of 2019 “was largely influenced by the restriction of water flowing from the upper Mekong during that time.”

“Cooperation between China and the Lower Mekong countries to simulate the natural flow cycle of the Mekong could have improved the low flow conditions experienced downstream between May and September of 2019.”

Assistance needed

The results of climate change and the recent drought, compounded by the damming of the upper Mekong, have had a devastating effect on the livelihoods of the people in the Tonle Sap region who rely on fishing as their revenue decreases and competition increases, according to the consultant, Ham Oudom.

“These people need government assistance in terms of finding new paths for revenue,” he said.

Tonle Sap Fishing Community Alliance chief Long Sochet said many residents of the lake region have been forced to take on debt from microfinance lenders in addition to what they already owe to meet basic needs, or send their children to work as domestic servants to try to earn more money for their household.

He called on the government to allocate some of the country’s budget to fishing communities that rely on the lake.

“For us who are living on the floating villages on the Tonle Sap, mostly, when there is no water and no fish, we become destitute right away, as we have nothing else to depend on,” he said.

Stimson’s Eyler warned that given predicted climate change impacts, the current drought, and the ongoing impact of the coronavirus pandemic, Cambodia is unlikely to have the resources to assist the communities that will be hardest hit by the transition of the Tonle Sap and the Mekong.

He urged Cambodia’s development and diplomatic partners to immediately provide assistance.

“I think the writing on the wall is clear, that Tonle Sap fisheries are on a severe decline,” Eyler said.

“Currently, the only option for fishers is to take on higher levels of debt,” he said.

“Those fishers are trying to service debt—many of them took on higher levels of debt last year—but that debt service needs to happen in a timely manner, and it cannot happen year on year on year. Otherwise, both individual fishers and the Cambodian economy will be broken.”

Reported and translated by Sovannarith Keo. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.