Landmines left over from Cambodia’s civil war half a century ago still injure or kill some 50 people a year – a sharp decrease from several years ago but still a worrisome issue for farmers and rural residents in the country’s western provinces.

There were about 100 casualties a year from landmines and unexploded ordnance during the decade that began in 2010, according to Heng Ratana, director general of the Cambodian Mine Action Center, or CMAC.

That number has dropped by half over the last three years, but challenges remain in provinces that border Thailand that haven’t been cleared, partly because mines were laid in remote areas years ago that aren’t accessible by road, he told Radio Free Asia

“In some of these areas, people won’t know there are landmines until they see them with their own eyes or step on them,” Heng Ratana said.

Thursday marked International Day for Mine Awareness and Assistance in Mine Action, and the government's Cambodia Mine Action and Victim Assistance Authority, or CMAA, held a ceremony at a ceremony in Siem Reap.

Cambodia is one of the most heavily mined territories in the world, with millions of landmines and unexploded ordnance that have killed more than 60,000 people since 1970. It has more than 530 square kilometers (204 square miles) that still need to be cleared of mines and ordnance, according to the CMAA.

Left over from war

The bombs and mines are left over from U.S. forces during the Vietnam war, but also include Chinese and Russian mines from the Khmer Rouge era in the 1970s and the Cambodian civil war of the 1980s.

Over the last 30 years, CMAC and other NGOs have found and destroyed more than 4 million landmines and unexploded ordnance. Among them are more than 1.1 million anti-personnel mines, more than 26,000 anti-tank mines and more than 3 million unexploded ordnance.

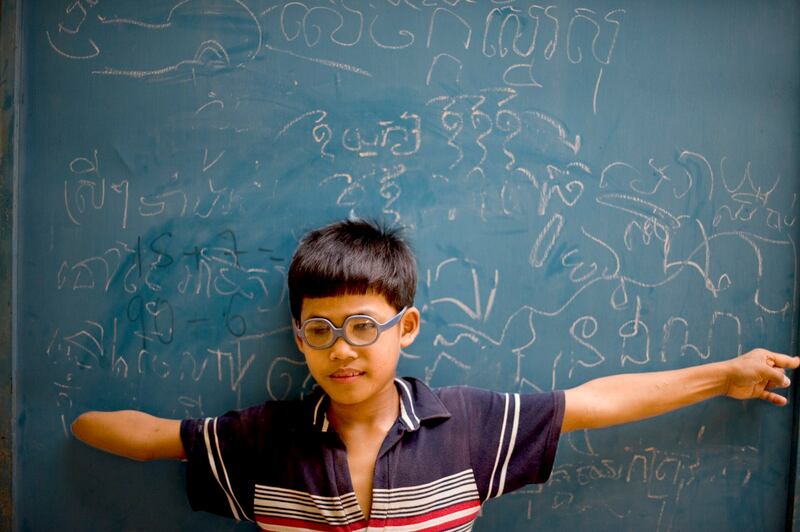

Most recently, a child was killed when a landmine exploded on March 17 in Oddar Meanchey province’s Anlong Veng district. Two other children were wounded, including the injured 4-year-old son of Beep Mab.

“The area was a Khmer Rouge rebel base and has never been de-mined,” he told RFA. “One boy, a 10-year-old, went to pick up mines from a stream near the foot of Dangrek Mountain and played with them.”

‘Still so many mines’

Ly Thuch, the CMAA’s first vice president, restated Cambodia’s goal of finding and removing all mines and unexploded ordnance by 2025.

But that objective seems unlikely to Beep Mab. In his commune, farmers consistently come across mines while plowing their field, he said.

“At the foot of the mountain, it is alarming because there are still so many mines left,” he said.

Thursday’s CMAA ceremony was attended by officials from a dozen foreign embassies and other international organizations. The enormous effort to demine Cambodia since the early 1990s has largely been funded by foreign donors.

In November, Cambodia will host in Siem Reap an international conference of signatories to the Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, also known as the Ottawa Convention.

Ly Thuch said in November that Cambodia will use the conference, which has been held every five years since it became international law in 1999, to refocus the world's attention on humanitarian assistance to victims.

“Cambodia looks forward to sharing its experience,” he said. “Siem Reap, once marred by the presence of these insidious devices, has now thrived after the successful clearance of landmines.

“Today, millions of people from all over the world visit the magnificent Angkor Wat temple complex, which stands as a testament to the transformative power of mine clearance.”

Increasing casualties in Myanmar

The Mine Ban Convention, signed by 164 countries, prohibits the use, stockpiling, production and transfer of anti-personnel landmines.

But the United States, China, Russia, India, Pakistan and Myanmar are not signatories to the treaty.

In 2023, civilian casualties resulting from landmines and unexploded ordnance nearly tripled compared to 2022 in Myanmar, which has seen intense fighting between the military junta, ethnic armed organizations and local militias since a 2021 coup d’etat.

A report from the United Nations Children's Fund released on Wednesday said there were 1,052 deaths and injuries across Myanmar in 2023. There were 390 casualties from landmines the previous year, the report said.

People in conflict-affected areas are at greater risk of fatalities due to their lack of knowledge about landmines, the report said, citing several mine awareness organizations.

A political analyst and former military officer said that both the military junta and the local People’s Defense Forces have been laying mines over the last few years.

“Of course, both sides are doing it,” he said, requesting anonymity for security reasons. “However, it is the PDFs whom I hold accountable, particularly for their lack of discipline and disregard for safety protocols concerning landmine usage.”

RFA was unable to reach junta spokesman Maj. Gen. Zaw Min Tun to ask for his comment on the report on Thursday.

RFA Burmese contributed to this report. Translated by Sum Sok Ry. Edited by Matt Reed and Malcolm Foster.