UPDATED at 1:20 p.m. EDT on 04-05-2023

Visitors are not welcome at the monkey farm co-owned by the sister of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen.

The farm is ringed by moat-like canals, 6-foot-6-inch-high (2 meters) earthworks and a brick wall topped with razor wire.

A former employee told RFA that guards with Kalashnikov assault rifles patrol the grounds inside the farm in rural Kampong Speu province, which is two hours’ drive from the capital Phnom Penh.

So, what’s there to secure behind the walls?

The answer is the captive animals within: long-tailed macaques, a breed of primate favored for medical research.

Once an unremarkable player in the business of providing the animals for a global research industry, Cambodia has become a hub for exports of long-tails – a lucrative but shadowy business tied to the nation’s political elite.

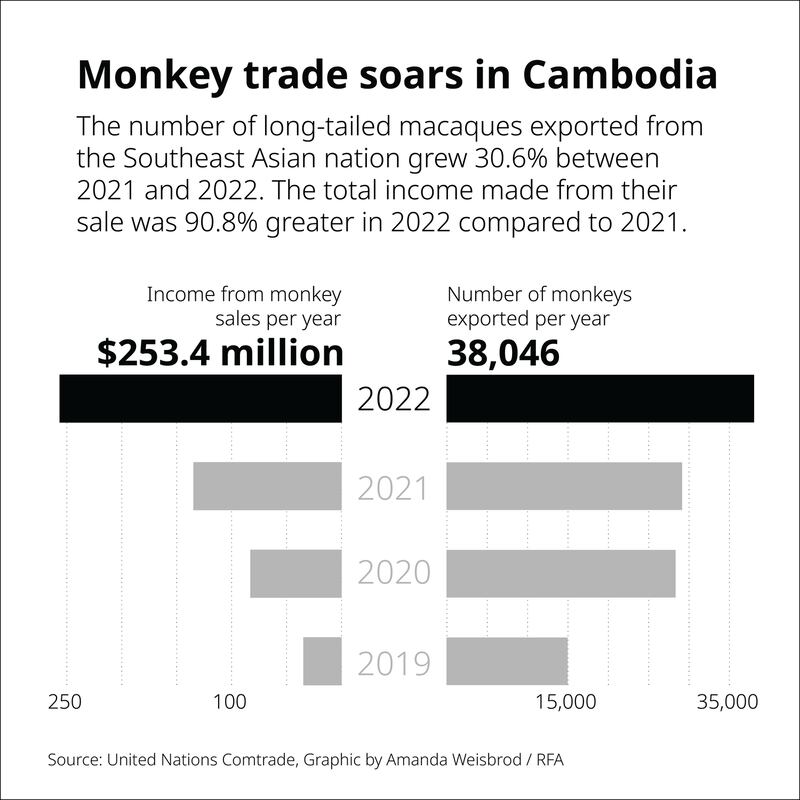

Growing demand from the COVID-19 pandemic meant primate farms like the one owned by the prime minister's sister exported about a quarter of a billion dollars worth of research macaques in 2022, according to U.N. trade data.

But as the business booms, questions are emerging about the origin of the monkeys Cambodia ships around the world.

Allegations of illicit trade are at the core of a high-profile legal case brought by U.S. wildlife prosecutors against senior Cambodian government officials.

Two officials have been charged with issuing fraudulent export permits certifying poached monkeys as captive-bred animals to circumvent U.S. import restrictions and international treaties governing the trade in endangered species. Cambodia’s wildlife and diversity director, Kry Masphal, was arrested in New York in November while traveling to a conservation conference in Panama. His boss, Forestry Administration Director General Keo Omaliss, was also indicted but remains at large in Cambodia.

Kry is currently under house arrest near Washington, D.C., and set to face a court proceeding in Miami in June.

Yet with so much money to be made in Cambodia, experts fear there is little incentive for reform in the country.

“It’s kind of like the realization of our worst fears,” said Ed Newcomer, a recently retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent who spent 20 years investigating wildlife crimes around the world.

“When government officials, and relatives of high-powered officials, are involved in the wildlife trade, how are the Cambodian regulatory and enforcement agencies supposed to effectively enforce the law?”

The monkey business

Long-tailed macaques, which are native to Southeast Asia, are so-named because their tails are usually longer than the length of their bodies. Other distinguishing characteristics include tufts of hair atop their heads and whiskers around their mouths.

Also known as “crab-eating” monkeys, they are highly prized by biomedical researchers for their similarity to humans. Testing on the animals helped lead to a vaccine for yellow fever. More recently, they’ve been used to test treatments for issues ranging from reproduction to obesity and addiction.

Demand for their species soared with the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, as macaques were critical in the development of the mRNA vaccines for COVID.

Until recently, China was the world’s top supplier. But in a bid to protect its own vaccine development, Beijing banned exports of research monkeys, leaving Cambodia as the number-one source for a global research industry that was suddenly facing a severe shortfall.

In 2019, Cambodia exported the most primates it had ever shipped in a single year, sending 14,931 overseas for $34 million – an average cost of just over $2,271 per monkey, according to the U.N. trade data.

The number of macaques being exported and the average cost per monkey continued to rise. Countries reported importing around $250 million worth of monkey shipments from Cambodia in 2022 alone, according to the data.

Questions of origin

But experts say it would be impossible for all of them to have been legitimately raised and sourced according to rules that govern the use of research primates.

Partly to protect dwindling wild populations, but also to reduce potential contamination of experiments, only captive-bred macaques are allowed in medical research. However, they are also slow-breeding, with infants taking three years to reach maturity. So, captive-bred stocks frequently struggle to meet researchers’ needs, and suppliers are often incentivized to pass off wild-caught monkeys as farm-reared.

Although a black-market trade in the monkeys has long blighted the industry, the COVID-driven supply shortage has sent illicit poaching into overdrive, conservationists say.

“There’s just too much money in this business now for these macaques to stand a chance,” said Lisa Jones-Engel, a primatologist who now advises the animal rights group Peta.

A study published last month in One Health, a peer-reviewed veterinary science journal, found that Cambodian breeders would have needed to more than quadruple production rates – from 81,926 over a four-year period to at least 98,000 in a single year – to have legitimately exported the number of macaques shipped during the pandemic.

As Cambodia has never reported importing long-tailed macaques, such an increase would have to have been driven entirely by an increase in domestic supply.

Yet “Cambodia has historically been incapable of producing second generation offspring macaques, therefore increasing their production capacity legally seems unlikely,” the researchers wrote.

The sister

The farm owned by the prime minister’s sister Hun Sengny sits at the end of a dusty road on the outskirts of the sleepy town of Damnak Trach.

It is registered under a Cambodian firm, Rong De Group, for which she serves as chairwoman. The uniforms of the security guards who wield the assault rifles bear the insignia of her private security firm, Garuda Security Co.

Locals who spoke to RFA all described the “boss” of the farm as being Chinese expatriate, Dong Wan De, who Commerce Ministry records identify as the Rong De Group’s only other director and shareholder.

Rong De Group was granted a breeding license for the farm in 2007, although Hun Sengny did not take control as chairwoman until 2011.

The Rong De Group farm, Hun Sengny and Dong Wan De have not been implicated in any wrongdoing, and Hun Sengny does not hold any government office in Cambodia.

But she is among the many with ties to political power – official or otherwise – who have enjoyed the fruits of being given free rein to undertake business ventures with little government oversight.

After spending much of the 1970s forced by the Khmer Rouge to work as a seamstress, Hun Sengny now has interests in mining, agriculture, logistics and consulting, often in collaboration with Chinese investors.

Hun Sengny and Dong Wan De did not respond to requests for comment.

Powerful players

In another example of the industry's connections to the powerful, Agriculture Ministry Secretary of State Sen Sovann told RFA that he has leased land in Kandal province for decades to James Lau, the founder of the Vanny Group, a company that operates monkey farms.

Lau was among six individuals indicted last year alongside Kry and Keo Omaliss, who as director of Cambodia’s Forestry Administration was Kry’s immediate superior, in the U.S. monkey importation case.

Sovann insisted there was nothing improper in the arrangement and said that he did not know what the land was used for.

However, public records for business addresses suggest the land he leases houses one of Vanny Group’s Cambodian monkey farms under investigation by U.S. wildlife officials in the case against Keo and Kry. Vanny Group’s farms are named in the indictment.

And in August 2022, then-Agriculture Minister Veng Sakhon flew to Seoul to sign a business agreement with Orient Bio, Inc. on behalf of the ministry, despite a U.S. Justice Department investigation into the company on suspicion of poaching and laundering macaques from Cambodia to the United States.

The Cambodian government has denied that there is a problem with illicit monkey trading in the country, despite calls by conservationists for tighter regulation of its farms for more than a decade.

In response to Kry’s arrest in the US, the Agricultural Ministry issued a statement saying that Cambodia’s macaques “are not caught from the wilderness and smuggled out, but farmed in decent manners with respect to good hygiene and health standards so as to preserve their gene pool.”

But such high-level interest in the business makes it hard for Cambodian wildlife regulators to oversee the industry, said Newcomer, the retired U.S. investigator.

“They are powerless because such powerful people are involved in the trade,” he said.

‘Voluminous’ evidence

But now the illicit trade in the primates has attracted the attention of U.S. authorities.

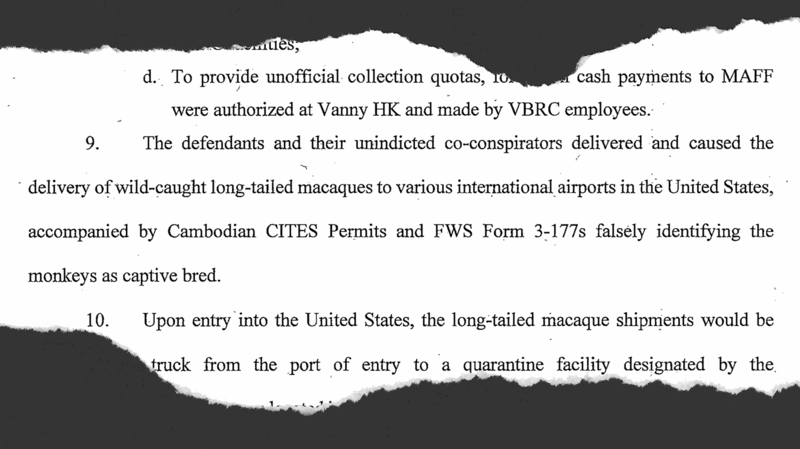

After a years-long investigation by Fish and Wildlife agents, U.S. prosecutors on Nov. 16, 2022, accused Kry, the Wildlife and Biodiversity director, and Forestry Administration head Keo of taking part in a multi-million dollar conspiracy to ship wild long-tails to the United States.

The indictment alleges the two colluded with monkey breeders to produce fraudulent export permits certifying the monkeys as legitimately sourced.

Kry was arrested in New York last November on his way to a wildlife conservation conference in Panama. Keo remains at large in Cambodia.

U.S. prosecutors have described the evidence against Kry as “voluminous.” Court filings reveal it includes blood and trace analyses, hundreds of investigative reports, video footage and financial records. In total, over 660,000 pieces of evidence have been turned over so far.

Kry has pleaded not guilty. His lawyers have not responded to repeated interview requests.

Where the demand is

But the blame for the criminality alleged by the Justice Department lies not just with the exporters in Cambodia. Importers in the U.S. and China who are fueling the demand bear responsibility, Jones-Engel of Peta said.

According to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, the U.S. imported some 300,000 long-tailed macaques over the last decade, five times as many as Japan, which reported the next highest imports over the same period.

It’s not known what proportion of those imports were illegally sourced. But industry players in the U.S. have known for years that wild-caught monkeys were making their way into shipments from Cambodia, U.S. investigators say.

Newcomer, the retired U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agent, went undercover at a Washington, D.C., trade show for the biomedical research and primate industry roughly a decade ago. Posing as a lawyer for a group of investors looking to set up a macaque farm in Cambodia or Laos, the things he heard were damning.

“When I approached in a nice suit and handed them my business cards from an established law firm, everybody assumed I was part of the inner circle of importers,” Newcomer told RFA.

Undercover, he heard incriminating statements, including admissions by representatives of U.S. primate importers, “that they knew wild animals were making it into their shipments from Cambodia.” The high bar for collecting enough evidence to indict meant investigators were unable to pursue charges, however.

Bleak outlook

Demand for long-tails led the International Union for Conservation of Nature to list the breed as an endangered species last year.

Hunting and trapping of macaques is taking place at “unprecedented levels … most ominously, to fuel both the legitimate and illicit trade for research and other usages,” it said.

“Both price and demand for [long-tailed macaques] as a trade commodity has skyrocketed during the COVID-19 pandemic, relative to the already regular and heavy pre-pandemic capture and trade.”

Over the last four years, monkey exports have generated half a billion dollars for the Cambodian economy, according to the U.N. data.

But the portion of that money ending up in the pockets of the ordinary Cambodians doing the poaching is small.

A former monkey poacher in Pursat province, an area northwest of Phnom Penh that includes a vast wildlife preserve, told RFA that even at the height of global demand last year brokers were only paying 700,000 riel ($175) per macaque. He didn’t know where they were going or what they were for, he said.

By the time those same monkeys were exported they were fetching an average of $6,660 a piece, the U.N. data show – a 38-fold increase between the point of capture and the moment of export.

Given the country’s dynamics, the outlook for Cambodia’s macaques looks bleak, said Timothy Santel, who prior to his retirement in 2020 supervised the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s investigation into Kry and Keo.

“Unfortunately, as I have seen in my 30-plus years, money and greed is often the root to most of these activities,” Santel told RFA.

“And when you sprinkle in corruption, it's usually a disaster for the critters.”

Correction: This story has been updated to correct a mislabeled photo.