A father and son have pulled the strings in Cambodia’s energy policy for the past two decades, and during that time their family have acquired several million dollars’ worth of real estate and farmland in the U.S. states of Florida and Georgia.

The father, Ith Praing, has held sway at Cambodia’s Ministry of Mines and Energy for even longer than the country’s strongman leader Hun Sen has been prime minister. Appointed vice-minister in 1984, 10 years later he was promoted to secretary of state for energy within the ministry and has held on to the post ever since.

His eldest son, Praing Chulasa, followed in his father's footsteps into Cambodia's energy sector. Today, he is deputy managing director Electricite du Cambodge (EdC), where his duties include overseeing procurement contracts worth millions of dollars.

In effect, Chulasa is calling shots at this state-owned company although it is 50 percent owned by the energy ministry run by own his father. Adding to ethical quagmire, EdC has had a virtual monopoly over electricity supply in Cambodia's capital since 1999, after which electricity prices for Phnom Penh residents skyrocketed.

In the subsequent 20 years, the Praings have been busy building a mini property empire of their own in the southern United States. Where they got the money to pay for it is murky.

Through careful investigation of publicly available property and financial records, Radio Free Asia has pieced together how the family have established a land portfolio, including a spacious villa and fruit orchards, covering some 196 acres and worth $5.5 million dollars. They have also benefited from farming subsidies from the U.S. Department of Agriculture totalling $450,000.

During his 35 years in power, Hun Sen has surrounded himself with trusted lieutenants who cling onto enduring positions of influence. Ith Praing is one of them. In 2008, he and his wife Nhem Seddha were awarded the Royal Order of Monisaraphon, typically bestowed on favored dignitaries for services to the nation.

As a young man, Ith Praing taught electronics at Phnom Penh universities until the Khmer Rouge took power in 1975 and forced him to pick rice in Kampong Cham province. In 1979, following the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia, he returned to the capital where he worked first as chief electrician in a distillery before becoming factory director.

Within five years he was energy vice-minister. After rising to secretary of state in 1994, he enrolled in a Californian private university which granted him a doctorate in business administration in 1997.

Property shopping spree

In the same year, his son Chulasa, an electrical engineer, completed a master’s degree in Grenoble, France, and with a French government scholarship, embarked on a doctorate in electrical power systems, also in Grenoble.

Meanwhile, his teenage siblings – accompanied by their mother, Seddha – were in America, preparing to embark on a shopping spree. By the time Chulasa was defending his PhD thesis in September 2000, his siblings – Raksmey, then 18; Reasey, then 19; Chhouksar, then 21; Chhouksar’s husband Sayla Pith, then 22 – had purchased nearly 60 acres of farmland outside of Homestead, a town roughly 30 miles southwest of Miami, Florida.

The land cost the family more than three quarters of a million dollars. Land registry records indicate that the only mortgage the teenage siblings and Seddha had taken out until then was for $105,200, suggesting the family had managed to accumulate more than half a million dollars spending money in the seven years since Cambodia began its transition to a market economy in 1993.

Salary figures for Ith Praing during the 1990s were not available. However, in 2017 the salaries of all Cambodian secretaries of state were increased to $850 a month. Praing’s official income at the end of the 1990s was certainly much lower. But, had he been making his 2017 salary, it would have taken him more than 76 years to earn the $779,000 purchase price of the farmland bought by his children before the end of 2000.

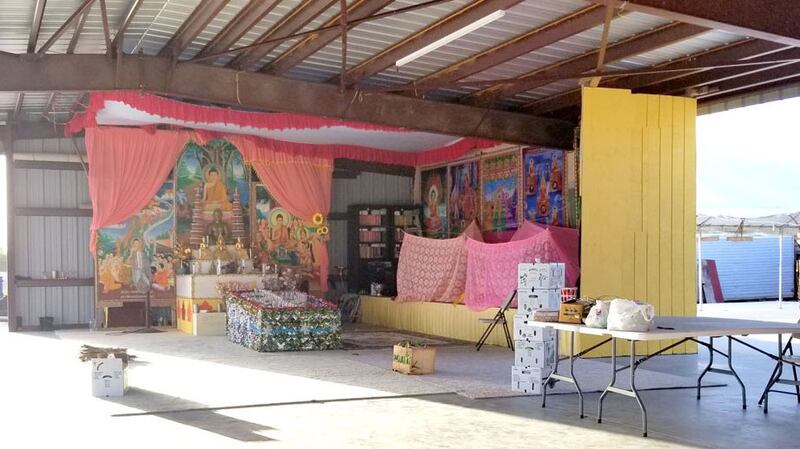

Raksmey, Reasey and Chhouksar all married and settled in Florida. These days the family are well-known around Homestead, where they run one of the largest agricultural wholesale operations and hold the key decision-making offices at a Khmer Buddhist temple that is under construction. They recently announced a $10,000 donation to build a pagoda there.

This past December, Chhouksar told a gathering that they had earned their money through honest means and part of it was profits from a golf course in Cambodia. She didn't, however, explain how the family got the money in the first place to build the course, which opened in 1997, billed as the nation's first.

Anti-corruption advocates briefed on the land purchases in Florida noted that they were highly unusual for two reasons: firstly, in the late 1990s it was uncommon for recent arrivals to the United States from Cambodia to be buying up large tracts of land. Secondly, it was uncommon for teenagers – Raksmey and Reasey were just 16 and 17, respectively, at the time of several of the purchases – to be investing in real estate at all.

A newly minted doctor of electrical engineering, Chulasa returned to Phnom Penh at the start of the 21st century to take over as director of planning at EdC. Neither Chulasa nor his father responded to questions sent by e-mail about whether the son was benefitting unfairly from Ith Praing’s seniority at the Ministry of Mines and Energy.

Nepotism can be “spotted throughout” the Cambodian government, according to Chak Sopheap, executive director of the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights. “There are no restrictions or rules against hiring family members, or even how many may be hired. This gap fosters the promotion, implementation, and acceptance of nepotism without any backlash,” Sopheap told RFA.

“In such conditions, without the necessary checks and balances, corruption is allowed to flourish,” she added.

Passports as political favors

Months before Chulasa took up his post with EdC, records show Seddha had left Miami and come back to Cambodia, taking up residence in a multi-storey, razor wire-protected villa in the capital's upmarket Tuol Kok neighbourhood.

The records, notarized by officials at the U.S. Embassy in Phnom Penh, show that Seddha possessed a Cambodian diplomatic passport.

Seddha could not be reached for comment and a Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson did not respond to questions about how Seddha came to have a class of travel document officially reserved for foreign ministry officials.

However, Cambodian diplomatic passports have reportedly been given out as political favors in the past. In August 2000, then-Foreign Affairs Minister Hor Namhong told a Cambodian parliamentary commission that despite only employing some 400 eligible diplomats, his ministry had issued in excess of 4,000 diplomatic passports.

The revelation came following a raid on the home of a Taiwanese crime boss in Seddha’s neighbourhood. The Cambodia Daily reported at the time that diplomatic passports were found in the house alongside a “large weapons cache.”

The paper quoted government and diplomatic sources saying the passports were highly sought after as they allowed the bearer “to travel throughout the region without scrutiny at immigration posts.”

In 2003, with a chunk of Florida of about 59 acres in the family name, the Praings built a home. Set back 175 feet from the road and shielded from view by privacy hedges and palm trees, the two-storey building has five bedrooms and three bathrooms. Today, the structure alone is estimated by the Dade County Property Appraiser to be worth more than $250,000.

The following year, Chulasa's name was added to the deeds to two patches of Florida farmland with a combined estimated value today of $1.5 million, with nearly 50 acres of fruit groves and a 5,000 square foot warehouse.

Putting down roots

The family would not purchase any more farmland in Florida for over a decade. However, between work finishing on the house in 2003 and the middle of 2006 they would take out mortgages totalling $1.5 million, according to Florida public records.

Florida was not the only place the Praing family put down roots. In 2007, they doubled the size of their U.S. agricultural holdings for a fraction of what they had previously spent by venturing north to the state of Georgia.

For $321,050 the Praings became the owners of 52 acres of land just outside of Adel, Georgia, and minutes’ drive from Cook County airport. Over the years the family would continue to acquire farmland on the edge of Adel, eventually coming to own an 83-acre portion of Cook County.

Starting in 2014, the family began using corporate vehicles to purchase even more land around Homestead, Florida. Between 2014 and 2018, companies controlled by Praing family members – Seddhanchan Group, LLC; Seddhachan Investments, LLC; and Louisville Miami Corp, which was purchased from a Floridian farming family in 2017 -- spent an average of $580,000 a year on agricultural real estate.

Chulasa – who by this time had been promoted to his current position of Deputy Managing Director at Cambodia’s state energy firm – was not listed as a director of any of the family’s companies.

In 2016, however, he and his siblings took out a joint mortgage of $300,000 to refinance the debt of one of the companies.

Chulasa did not respond to questions about how he manages to keep up the repayments on such a large mortgage on a civil servant’s salary.

All told, in the 20 years from 1998 to 2018, the Praing family have accumulated almost 200 acres of U.S. farmland, spending at least $3.57 million in the process.

However, in the same period they took out mortgages for just $2.38 million, leaving an almost $1.2 million shortfall to be picked up by what is a family of young Cambodian emigres and civil servants.

Red flags

The absence of either full financing or an explainable source of cash should have been a “red flag” to professionals involved in the transactions, according to Gary Kalman, director of Transparency International’s U.S. chapter.

“This case is tragic but not surprising. The story simply and clearly explains why weaknesses in U.S. laws make this country a magnet for illicit cash,” Kalman told RFA.

The Praing family acquisitions in America haven’t gone unnoticed by Hun Sen. During a July 29, 2019, speech in Phnom Penh that hinted at the sensitivity of high officials parking wealth overseas, the prime minister invited the U.S. government to seize the assets of Ith Praing’s children because they are Americans.

“They (the U.S. government) can seize assets of their own people as they please,” Hun Sen said at a ground-breaking ceremony for a stadium bearing his own name. “And if there are any government officials who have too much money and it’s kept in the U.S., I would be very happy to see their money seized by the US government as well.”

What Hun Sen didn’t mention is that his own children once had a house of their own in Long Island, New York, that they acquired in 2000 for $550,000, not long after the Praings started buying up land in Florida.

While it is true that the U.S. real estate industry is largely exempted from due diligence obligations, the same is not true for the banks that processed the Praing family’s $2.38 million of mortgages.

Thanks to Ith Praing’s role as a senior government official and Chulasa’s position as a management executive at a state-owned enterprise, they qualify as what is referred to in due diligence circles as “politically exposed persons,” or PEPs for short.

Guidelines drawn up by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – and widely adopted by regulators and oversight bodies – call for financial institutions to be extra vigilant when it comes to foreign PEPs, due to the higher likelihood of their being the recipients of ill-gotten wealth.

'Politically exposed persons'

Banks are required to actively assess whether their clients might be PEPs. If they are found to be, senior management approval must be gained before doing business with them. The bank must then “take reasonable measures to establish the source of wealth.”

Crucially, FATF guidelines call for the family members of PEPs to be considered politically exposed as well.

As such, the whole Praing clan qualifies as PEPs and, in theory at least, their mortgages ought to have been placed under enhanced scrutiny by the banks.

But if alarm bells should have been ringing in America, so too in Phnom Penh.

In 2015, Chulasa signed another document in connection with the $1.5 million Florida real estate in which he had an interest. His signature was witnessed by two fellow executives at EdC and notarised by a Phnom Penh lawyer who specialises in – among other things – energy matters and counts multiple Cambodian government ministries as his clients, although it is not clear if EdC or the Ministry of Mines and Energy was ever among them.

On the document, Chulasa gave his address as the same Tuol Kok villa that Seddha – who now had a United States permanent resident’s card and listed her address as the family’s Homestead farmhouse – had given as her own address 15 years earlier.

The villa is not the only building in the neighborhood the family have an interest in. Starting in 2008, the Praings renovated a seven-storey tower block directly behind the villa, converting it into 21 luxury apartments.

In mid-December 2019, the family established at least six new Florida corporations, each named with initials. Five of them are named “SDCH” followed by the numbers one to five. The letters appear to be an abbreviation of “Seddhachan,” the name borne by the luxury Tuol Kok apartment block as well as companies owning more than half of the family’s real estate investments by value.

While it is not yet apparent what purpose the six new companies will serve, the fact of their being incorporated en masse suggests the Praings are not planning on closing up shop any time soon.

And why would they be? Agriculture has clearly been very good to the family, thanks in part to the U.S. government's Department of Agriculture, which over the last two decades has granted the Praings farming subsidies totalling close to half a million dollars. More than 99 percent of that came in the form of "disaster subsidies," doled out to farmers in the wake of hurricanes.