Cambodian opposition leader Sam Rainsy said Tuesday he believes the United States and European Union can still push his country back on a path toward democracy, even as Prime Minister Hun Manet’s government shows little apparent desire to allow open dissent.

The Cambodian government has suppressed any semblance of an opposition inside the country over the past decade, dissolving Sam Rainsy's Cambodia National Rescue Party, or CNRP, and preventing its successor parties from taking part in subsequent elections.

Like many other opposition figures, Sam Rainsy – 75 years old and living in Paris – is also subject to multiple arrest warrants if he returns home. His CNRP co-founder, Kem Sokha, has been under house arrest in Phnom Penh for years and was last year sentenced to 27 years in prison for "treason."

But in an interview with Radio Free Asia outside the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on Tuesday, Sam Rainsy said that he hoped to convince U.S. lawmakers and the Biden administration that they should not give up on Cambodia’s pro-democracy movement.

“We would like to see the U.S. administration put continuous pressure on the Cambodian government to release political prisoners, to allow a guarantee for freedom of expression and to organize free and fair elections,” he said. “But so far, this has not been achieved yet.”

Growing economic troubles in both Cambodia and its modern-day patrons in Beijing, he said, was creating a situation in which the West could have newfound leverage in Phnom Penh’s decision-making.

Pressure campaign

For years following the 1991 U.N.-organized elections in Cambodia, U.S. and EU governments forced then-Prime Minister Hun Sen to at least pay lip service to democratic ideals and allow a veneer of open society as a condition of receiving billions of dollars in aid money.

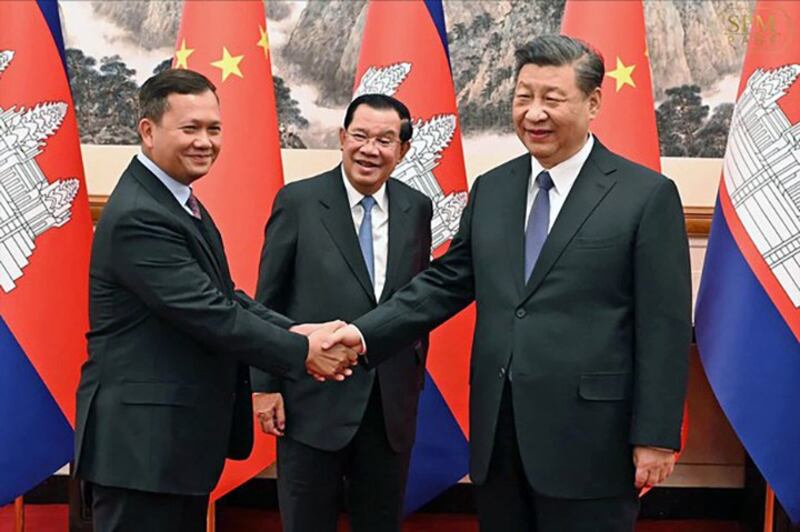

But an upgrade in ties between China and Cambodia in 2011 and a subsequent windfall of Chinese aid and investment decreased Phnom Penh’s reliance on Western governments, and allowed Hun Sen’s government to increasingly ignore any outside pressure.

And while the United States and European Union in the 2010s threatened to cut Cambodia off from lucrative trade concessions that prop up the country’s dominant garment export industry, it did not stop the repression of the opposition at the 2018 and 2023 elections.

Since 2023, though, the United States has sought to move away from pressing Cambodia's government to move back toward free elections to instead seek ways to accommodate Hun Manet and his new government in an effort to stop it getting any closer to Beijing.

But Sam Rainsy said it was only through continued direct pressure that Cambodia’s government would decide to change course.

“Dialogue with Hun Sen, or with Hun Manet, is an illusion,” Sam Rainsy said. “I hope that the U.S. administration will realize that soon.”

“They have been wasting a lot of time believing or hoping the Hun Sen regime will liberalize or will distance itself from China,” he added. “Real and fruitful dialogue with any dictator is just impossible.”

Ticking clock

The longtime opposition leader said that the West should not give up on hope for a pluralistic Cambodia.

A recent “charm offensive” by Hun Manet to attract Western investment “shows that China's support is not enough” to shore-up Cambodia’s struggling economy, Sam Rainsy said, and put America and Europe in “a unique position to really push Hun Sen to make concessions.”

Meanwhile, as the years go by, Hun Manet will inevitably strive to establish a sense of legitimacy for his own rule and seek to emerge from his father’s shadow, he added, providing U.S. and EU leaders another avenue to pressure the government to change.

“Hun Sen is not eternal,” Sam Rainsy said. “He is almost 72 now, and he will not be leading the country – or at least pulling the strings from behind the scenes – for too many years to come.”