In a turnaround, the Cambodian government has decided to set aside land for more than 1,000 families threatened with eviction at a controversial development site in the nation’s capital.

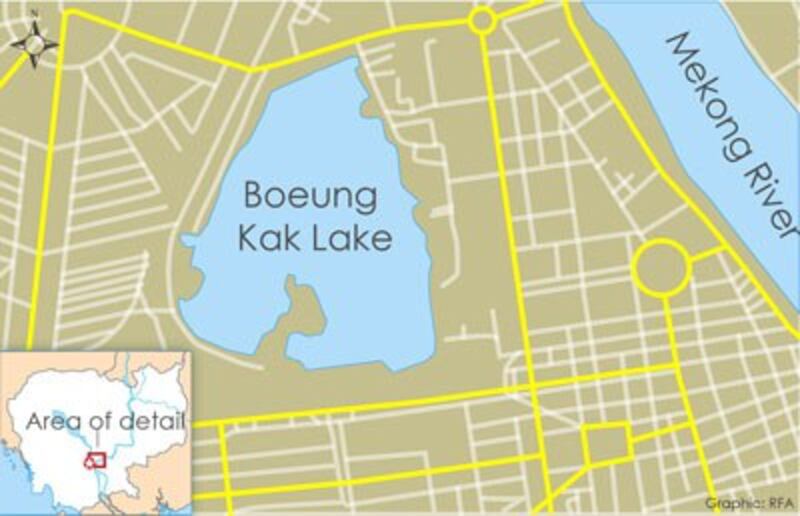

On Tuesday, Council of Ministers spokesman Phay Siphan confirmed that Prime Minister Hun Sen will reserve 12.5 hectares (31 acres) of land at Boeung Kak Lake in Phnom Penh for villagers to develop themselves.

The announcement came on the heels of a decision by the World Bank last week to halt new loans to Cambodia until the land dispute was resolved.

“The decision was not because of the World Bank’s pressure,” Phay Siphan told RFA. “This is the government’s stance.”

The settlement could bring to an end the long-standing dispute, which has seen 3,000 families forced from their homes as a Chinese-Cambodian company owned by a politician from the ruling Cambodian People’s Party fills in Boeung Kak Lake to build a luxury residential area.

Many families have been forced to accept what they consider inadequate compensation from the government.

Villagers and rights activists have remained skeptical about the government’s deal with the 1,000 families who had refused to budge from the site, saying there was no guarantee it would be implemented at the local level.

Boeung Kak villager Tul Srey Poeu welcomed the government’s decision, but expressed concern that corruption and mismanagement by local authorities might leave residents landless in the end.

“The government must make sure that the local authorities will put the plan into action,” she said.

She said the central government may be less motivated to follow through on implementation because they had simply cut a deal with the villagers to restart funding from the World Bank.

“The government’s decision came after the bank’s pressure, and not because of the government’s good intentions.”

Rights activist Chan Soveth, with the domestic nongovernmental organization ADHOC, also voiced suspicion regarding the deal, citing past government pledges to grant land to villages that were unfulfilled.

“The government should settle all of Cambodia’s land disputes—not only the Boeung Kak issue and not simply as a reaction to the bank’s pressure.”

Bank pressure

In March, an independent inspection panel found that the World Bank had mishandled a land titling program that led to the eviction of residents from the lake district over the past two years.

Following the panel’s findings, the bank offered to help the government find a solution for the residents, but it also warned that it would reconsider its work in the country if the forced relocations were not halted.

Last week, the bank issued a statement saying it would freeze all funding until the dispute was resolved, showing that it means business in Cambodia, where its last loan was provided in December last year.

In the meantime, the bank has said it will continue to honor its existing commitments to the country.

Responding to the bank’s statement, Phay Siphan told RFA last week that the government would not fold to pressure, calling the decision an “abuse of Cambodia’s integrity and its independence.”

The families who remained at Boeung Kak Lake had held frequent protests in recent months, saying they were holding out for property on the same site after the construction is complete, or for greater compensation.

They say they are entitled to the property under Cambodia’s Land Law, though few of them possess titles, because they have squatted there for decades.

Police and company workers had threatened and harassed the residents in attempts to prevent them from holding meetings and from peacefully protesting against the forced eviction.

Police had also used excessive force against some residents when they gathered to bring the issue to the attention of visiting dignitaries and Cambodian politicians, rights groups said.

Ongoing issue

Cambodia’s land issue dates from the 1975-79 Khmer Rouge regime, which forced large-scale evacuations and relocations throughout the country. This was followed by mass confusion over land rights and the formation of squatter communities when the refugees returned in the 1990s after a decade of civil war.

Housing Cambodia’s large, young, and overwhelmingly poor population has posed a major problem ever since.

An estimated 30,000 people a year in Cambodia are driven from farmland or urban areas to make way for real estate developments or mining and agricultural projects.

Reported and translated by Samean Yun for RFA’s Khmer service. Written in English by Joshua Lipes.