More than two decades since agreeing to a memorandum of understanding for sharing fossil fuels in the Gulf of Thailand, Cambodia and Thailand are poised to resume the efforts. However, ongoing disputes regarding the ownership of Koh Kood Island might present a hurdle, especially amid public scrutiny.

The two neighboring countries agreed to discuss further the joint exploration of the hydrocarbon resources in the Overlapping Claims Area next to the island, Thai Prime Minister Srettha Thavisin told a joint press conference on Feb. 7 in the presence of his Cambodian counterpart Hun Manet, who was visiting Bangkok.

Srettha was referring to the 2001 MOU signed during the tenure of the former Thai leader Thaksin Shinawatra, who was removed from power in a 2006 military coup. The telecommunication billionaire, who enjoys enduring cozy ties with Cambodia’s former Prime Minister Hun Sen, was accused of betraying the nation for his own interests because he had invested in Cambodia.

And February’s announcement led to a Senate censure debate in Thailand this week.

Bangkok has yet to form a new technical committee to consider pursuing the MOU, the Thai foreign minister told the Senate on Monday.

“I personally think the negotiation should simultaneously cover both aspects,” Foreign Minister Parnpree Bahiddha-Nukara told the senators. “According to the 1907 Franco-Siamese Treaty … Koh Kood belongs to Thailand.”

The 2001 Thai-Cambodian MOU ties together border delimitation and resources sharing into an “indivisible package,” mandating that both aspects are to be addressed concurrently.

“In regard with concerns over betrayal, loss of territory and sovereignty, I believe all of these will not happen,” he said, adding that it will take another 10 years to utilize the underwater resources even if the two strike a deal.

‘No man’s land’

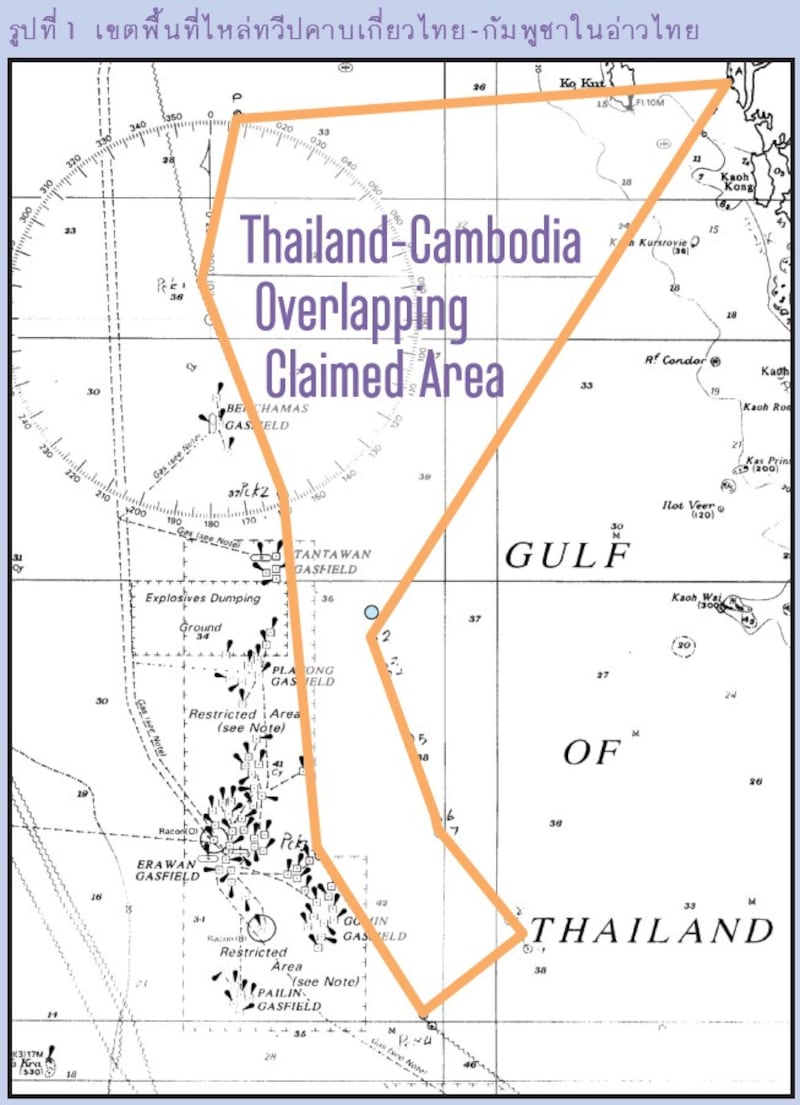

The roughly 27,000 square kilometers (10,425 square miles) area along the borders is filled with an estimated 5 trillion baht (US$138 billion) worth of natural gas and oil, according to PTT Exploration and Production PLC, Thailand’s petrochemical giant.

For decades the area was left unexplored because it is deemed “no man’s land,” said the Petroleum Institute of Thailand. Resource-sharing could feed the two energy-hungry Southeast Asian nations, it suggested.

But Cambodia’s delineation of the continental shelf splitting Koh Kood in half in 1972 remains irking Thai military-appoint Senators and nationalist activists.

Koh Kood is a second major disputed zone out of the entire 798-kilometer border drawn during the French colonization of Indochina. The historical rivals fought bloody clashes around the ancient Hindu Temple of Preah Vihear in 2008-2011 after Cambodian built a road network to the west of the shrine. The International Court of Justice ruled that the shrine belonged to Cambodia but not the adjoining vicinity.

The demarcation is a tricky business because Thailand claims that the Franco-Siamese Treaty of 1907 gave Koh Kood to it while Cambodia in 1972 expanded the special economic zone overlaying beyond the resort island, according to Thai officials. Thailand introduced its own a year later.

Past two Shinawatra-linked governments succumbed to blood-letting protests and were forced out of office because they were accused of doing too little to drive out Cambodian soldiers who occupied lands around the Preah Vihear temple in 2008.

Public outcry

Following the February press conference, Thai social media users questioned Srettha’s will to protect the country’s interest or he would concede the sovereignty over the disputed area.

Dozens of nationalists rallied at the Royal Thai Navy headquarters in Chon Buri, southeast of Bangkok, to defend Koh Kood.

In response, the Royal Thai Navy kicked off military exercises that will last until June.

“This exercise has an objective to train personnel for war readiness,” Navy Chief Adm. Adung Pan-iam told reporters at Had Yao beach in Chon Buri province. “Should we have to conduct any operation; the Navy must win.”

An analyst, however, supported bilateral talks for a peaceful resolution.

“Although Thailand may possess a more formidable naval force, resorting to military might is not a sustainable method for permanently resolving territorial disputes, as it often results in undesirable consequences,” Supalak Ganjanakhundee, a Bangkok-based Southeast Asia analyst, told Radio Free Asia.

“Negotiating within the framework established by the 2001 MOU offers the most promising avenue for achieving a peaceful resolution that respects the interests and concerns of both Thailand and Cambodia.”

Edited by Taejun Kang and Mike Firn.